Crumb (Special Edition)

Dir. Terry Zwigoff, U.S., 1994

by Sarah Silver

Boy, does Terry Zwigoff ever love comics. And comic artists love him! Underground comic staple Daniel Clowes has found a sardonic soul mate in Zwigoff, whose show-no-mercy directing style has now twice brought to the screen the sullen rejects and deluded dullards populating Clowes’s graphic worlds (first in 2001’s Ghost World and now with Art School Confidential). Diminutive, disgruntled caricatures of Zwigoff have appeared in pal Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor comics as well as in the sketchbooks of Robert Crumb, a friend, musical collaborator, and the documentary subject of Zwigoff’s harrowing and poignant Crumb (1994).

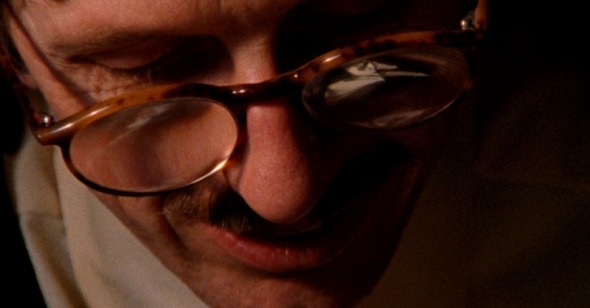

With one documentary portrait of an American musician, painter, and all-around wildcat already under his belt (1985’s Louie Bluie, about bluesman Howard Armstrong), Zwigoff, although lauded by critics, decided to take a nine-year hiatus from the public eye, much of which was spent immersed in the world of comic book artist Robert Crumb. The result is a highly personal portrait, very obviously crafted by a close friend: every interview with Crumb feels like it’s lit to lovingly caress the nerves he is unabashedly exposing for us. On more than one occasion, the camera patiently and nonjudgmentally takes us panel by panel through a comic as Crumb provides audio commentary to some of his more nightmarishly sexual strips. It is this patience and lack of judgment, no doubt, both behind the camera and in the editing room, that elicited the trust and confidence necessary to create such a raw, nuanced depiction of a truly original and important American artist.

Everyone has something to say about Robert Crumb, from reclusive relatives to borderline “TMI”- providing ex-girlfriends, to adoring art critics, to incensed feminists. All are given ample time to make legitimate points, which negates any critique of the film as a simple, adoring fan piece. On the contrary, the exploration of various viewpoints serves not only to further the film’s credibility but also to bravely reveal more and more layers, potentially objectionable or unflattering, to the Crumb persona. To ex-girlfriends he is the depraved little man who, by turns, undermined their confidence by cheating, or boosted their self-images to dizzying heights by drawing, and subsequently glorifying, their hefty legs and ghetto booties. To art critics he is the “Daumier of our time…” or the “Bruegel of the second half of the century,” with “Goya’s sense of monstrosity…” To certain feminists, he is the anti-Christ for depicting, and thereby “validating for young males,” feelings of sexual anxiety and hostility towards women. To his brothers, he is just Bob, who, in comparison to them, didn’t turn out half bad.

One assumes that Robert Crumb is the film’s titular character, but the film is largely about the Crumb family. Brothers Charles and Maxom are major players, each representing alternative routes to how a child raised in the Crumb household could have turned out, and each manifesting a different degree of mental illness. All three brothers, at one point or another in their lives, found a great deal of comfort and refuge in making art. Charles, the eldest, was able to channel his uneasiness into meticulous, compulsively drawn comics as a younger man, but, coming into middle age, his mental health has tragically disintegrated to the point of his being a complete shut-in, still living with his mother at age 50, and reliant on antidepressants. Youngest brother Maxom, loopy and unwashed, practices cleansing rituals such as sitting on a bed of nails several times a day and eating a long, shoestring-like object in order to purify his system. Made to feel an inferior artist as a boy, Maxom has come around to painting in adulthood. Only Robert was able to consistently sublimate his perversions and insecurities into his art from childhood into adulthood, and with enough success to actually get him laid, thereby contributing to a generally healthier outlook than that of his brothers.

Terry Zwigoff is perpetually fascinated with the relationship of art to its makers, to its critics, and to its consumers and aficionados. The beginning of Art School Confidential may as well be portraying a young R. Crumb, frustratedly vying for the attentions of girls but getting nowhere because they don’t yet know how to appreciate sensitive “artistes.” Rarely in film does one find a subject so well suited to the filmmaker’s style and interests as Crumb is to Zwigoff’s. That we have this beautiful document of such a relationship is not to be taken for granted.

The only feature putting the “Special” in this “Special Edition” DVD is a commentary/conversation between Zwigoff and Roger Ebert, who largely states the obvious by simply explaining what’s about to take place in any given scene. However, Zwigoff offers some pertinent information about the actual logistics of getting the film made, as well as some insights into its tragicomic subjects, and insider information to which he, a family friend, was privy. The devastating news that Mother Crumb, with whom Charles resided his entire life, destroyed all of his artwork immediately after his suicide, is an example of such information.