Woman of the Year

By Leo Goldsmith

Nobody's Daughter Haewon

Dir. Hong Sang-soo, South Korea, No distributor

One of the enduring canards of that devilishly intractable film-critical tick known as auteurism is the notion that a certain filmmaker has obsessions, idiosyncratic (and, ideally, perverse) fascinations that find their way, almost furtively, into their movies like so many under-analyzed repetition compulsions.

With Hong Sang-soo—a director whose career, I’ve come to speculate, is maybe just an elaborate send-up of the very concept of auteurism—things are a little different. It’s hard to miss Hong's repetitions. Once you've seen a few Hong Sang-soo films, you come to know pretty much what to expect: women and men, long single-take dialogue sequences, soju and regret, the occasional curiously timed zoom, a small number of locations which the film cycles through almost automatically. But these repetitions are less like obsessions and more like habits and, indeed, much like the characters' habits—difficult to get out of. They’re like taking the same walk to work every day, or the body-memory of unlocking your front door, or your selection of romantic partners with similar attributes you unconsciously deem to be complementary to your needs. It's a mundane cycle, punctuated only occasionally by fits of drunkenness or melancholy, which, if you're lucky, might be interrupted by some kind of catharsis (or catastrophe).

But, as many have noted, there has been one small evolution in Hong's films amid their comically stubborn consistency: the gradual shift in their centers of gravity toward their female characters (although admittedly not always with the most salutary ends). The early films, like Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors and Woman Is the Future of Man, were grim portraits of women being manhandled by man-children, and it was only around the time of 2005’s Tale of Cinema (of all of Hong's underrated films, perhaps one of the most so) that some hopeful glimmers from the earlier films begin to shine through: narrative elusiveness, or rather the ability of Hong's female characters to elude the strictures of his narratives, becomes much more of a priority here, one confirmed in Woman on the Beach, which concludes with one of its heroines quite literally becoming unstuck.

His latest films have pursued variations on these rhythms—or rather a lack of variation, the cyclical nature of daily living, and the rigor of convention in relationships (familial, professional, and especially sexual). Hong's principal terrain of late has been typically close to his own experience: where earlier films often followed struggling filmmakers during their seemingly infinite downtime (usually at the bottom of a soju bottle), more recent projects roam the outskirts of anonymous film schools, where student-teacher formalities variously persist, break down, and yield expectedly awkward results.

This is where we find Haewon, a young acting student and the lonely, motherless child the title promises. Only, she's not exactly motherless: as she explains in her (dream-)diary narration, her mother is about to move to Canada, so they plan a pleasant mother-daughter stroll around a park, a historical site, her mother's childhood neighborhood, then to a nearby bookshop and a cafe—in other words, the usual sparsely populated, rigorously framed public spaces that serve as sets for Hong's scenes. As if Haewon wants for mother figures, Hong has her bump into Jane Birkin on the way to meet her mother, in one of those curious one-off moments in Hong's films. The two exchange some giggly compliments on their mutual beauty, and Jane even suggests that Haewon looks like her daughter, Charlotte Gainsbourg.

She doesn't really, but then the women in Hong's films are always being told they resemble someone else or that they're pretty, so much so that it becomes a kind of curse, something to be held against them. Haewon also has this sort of oblique image problem. Late in the film, a kindly professor from San Diego she meets tells her, “You seem cold and self-centered on the outside, but on the inside you're the bravest person.” Neither of these observations seems especially true, and in any case the kindly professor has only just met her. (Haewon still contemplates marrying him.) We also learn that her fellow students resent her for what they insinuate are her upper-class pretensions and her “mixed blood.”

Her classmates may have other reasons to resent her, though: chief amongst these is her former relationship with Seong-joon, a director and professor at the film school. Once Haewon finds herself newly motherless, she reaches out to her former teacher/lover for company, thus initiating more strolls in the park, more awkward liaisons, and an extended drinking session. And here we enter the habitus of the slightly desperate middle-aged college professor. Played by Hong veteran Lee Sun-kyun, who has appeared in a number of his films, including Oki's Movie and Our Sunhi, the other film Hong made this year, Seong-joon inhabits the role we've come to identify as the Hong surrogate. He's prone to inappropriate nights out with his students, and, as one of them notes, likes to “make fun of intellectuals” in his films. But then it's also possible that this is just another red herring: another game played with the viewer's expectations of how an auteur ought to be pursuing his obsessions and exorcising his demons.

In any case, Hong is merciless with Seong-joon, who easily falls back into a casual relationship with Haewon, despite being married with a new baby, and who in his dealings with her vacillates wildly between sympathy, sentimentality, pettiness, and desperate, childish rage, calling her a “crazy bitch.” By the end of the film, Seong-joon's signature move is to collapse on a park bench, listen to his favorite song, which he plays on a portable cassette player (!), and cry. This is the ineluctable pull of Hong's narrative mechanics at work: once locked into the pattern of meeting and talking, always in the same parks, the same cafes, the same bookshops, there is no escape—at least not until someone is properly humiliated, or dissolves into a puddle of pitiable emotion.

“There's no such thing as a secret—everyone eventually finds out.” Or so Haewon warns Seong-joon, but both try to maintain their secrets anyway, as if they don't know how things will play out (or have never seen a Hong film before). Like a few of Hong's films, Nobody's Daughter Haewon toys with the idea that certain scenes are dreams—not so much to play with the borders of fantasy and reality as to suggest that trying to distinguish between the two is a fruitless exercise—and the characters seem to comport themselves as though trapped within one, acting out perverse, unaccountable compulsions or patterns of behavior. Even Haewon, despite the apparent sagacity of her earlier comment about secrets, later confides about her relationship with a couple of old school friends. And of course it all comes out in the end, amid tears and soju. This sense of inevitability—at its most mundane, and not in the more epic sense of fate or destiny—is what seems to drive Hong's films forward (if in fact that's where you're going), and I suppose your enjoyment of the film rests on whether you find that enervating or, like Hong, utterly hilarious.

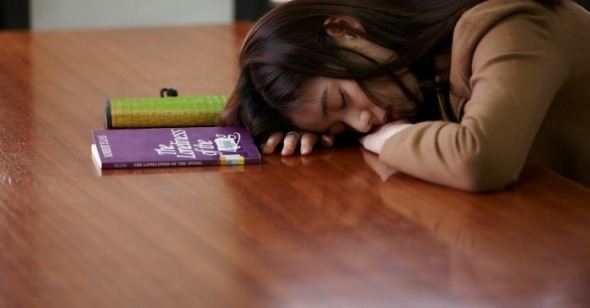

But, importantly, there is usually a rupture to break the spell. By the end of the film, once the repetitions have exhausted themselves (and the characters, as well), there is something like a moment of clarity. Fleeting though it may be, there is nonetheless a feeling of having completed the routines the film has set out and, perhaps, achieved a sort of understanding. A character wakes up, frees herself from the film's complex architecture, and simply walks away. It might be too much to hope for catharsis, much less transcendence, but at least we might be able to move forward.