Twitch City

By Daniel Cockburn

Frownland

Dir. Ronald Bronstein, U.S., Self-Distributed

Early in Ronald Bronstein’s debut feature Frownland, Keith Sontag (Dore Mann) sits in a car, waiting for his friend Laura (Mary Wall), prying his own eyes open for an interminable length of time. It’s a fitting mission statement for the entire film: staring open-eyed wider and longer than is comfortable. Audience reaction to this scene can vary from nervousness to laughter to boredom; we still haven’t received many cues as to what this movie is. To what end these open eyes, this long-held stare? That this mini-scene withholds emotional signposts, but not a payoff, is also representative of the film to come.

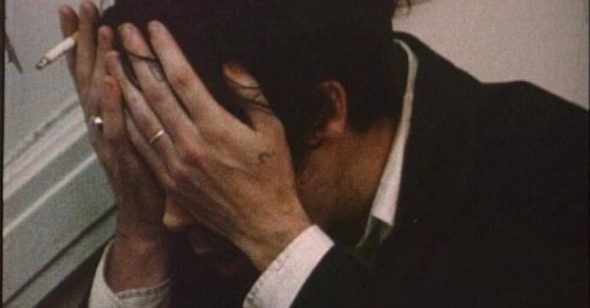

For the most part, Frownland tethers us to Keith (incarnated by Dore Mann in a prodigious, contentious train wreck of a performance), a man whose mouth full of abortive verbiage is his own greatest obstacle, as he scrabbles desperately not so much to navigate a plot as to keep up with life. He’s sleeping in the kitchen of a one-bedroom NYC apartment while his flatmate, Charles (Paul Grimstad), defaults on the electric bill, and this situation comprises a goodly portion of Frownland’s story; other threads include Keith’s workday torture as a door-to-door coupon salesman, his visits to reluctant confidant Sandy (David Sandholm), and his attempts at consoling Laura, the one person in Frownland who might be more damaged than Keith (that the film never even approaches her reasons is exemplary of its fascinatingly frustrating dance around emotional/narrative safe zones).

The circuitous lengths to which Keith goes in dealing with his life’s basic conflicts comprise much of the film’s discomfort and humor . . . but describing the film as such makes it sound a little too familiar. The conflation of the comedy of embarrassment with the tragedy of alienation has practically become a syntax: we know that a faux pas in The Simpsons or a Todd Solondz film will be followed by a cut to blank-faced listeners (cue the tumbleweed); we can practically sing along with Travis Bickle or Ricky Gervais as they dig themselves deeper into their conversational holes. Filmmakers and audiences are by now well schooled in the mechanics of awkward reactions to awkward situations, and when in the film’s opening Keith responds to Laura’s contextless anguish with a barrage of stammers, pauses, and pronounced facial tics, the viewer may well prepare herself for a performance (and a film) laboring to imitate some pre-established idea of awkwardness, a paint-by-numbers misfit.

But not for nothing has Frownland been called “Lodge Kerrigan’s Napoleon Dynamite” (by Spencer Parsons of the Cinematexas Festival, whose last-ever screening in December was Bronstein’s film, which remains without North American distribution). Where Napoleon Dynamite’s misfittery is made to go down easy, Frownland takes Kerrigan’s approach of pinning the audience’s eye to a character, and performance, that it will take some time and effort to understand. If his tic at first seems like an affectation, it eventually becomes apparent that, yes, Keith/Mann is doing it on purpose… but the truth is that a nervous tic is sort of on purpose; it’s a long-term burden but a short-term solace. To have a nervous tic is to be intimately acquainted with the grey zone between voluntary and involuntary. Frownland knows that this grey zone is also where performance lives. What matters is not whether the character, or the actor, intended to do this thing or not, as though intent or lack thereof would make it true or false; what matters is whether they needed to.

Frownland is full of need. Keith’s rollercoaster monologues are born of a desire to connect—unfortunately, every word he speaks is a wedge between himself and the listener. According to Bronstein, the film itself was born of a similarly self-negating compulsion, the craving for connection in a city of people with whom you share a mutual disgust. It’s also a financial need, and that Keith has fallen by default into a job for which he could not be less suited—and which in fact is a repeated crash course in rejection—makes it clear how his lack of human contact and his money troubles form a cruel feedback loop.

There’s a scene in which Keith overstays his forced welcome at Sandy’s place and falls asleep on the couch; Sandy discreetly fast-forwards to the end of the movie he’s watching so he can tell Keith it’s time to go. The meta-joke of the scene is that we are watching someone compress ninety minutes into three, but we’re still watching him do it in actual time. A “savvier” filmmaker would have given us the gag through montage; instead we are made to squirm through the uncomfortable duration Sandy will endure in order to avoid spending time with Keith. Making the viewer complicit in voyeurism is old hat by now, but this is maybe the first time a movie made me feel complicit in being an asshole.

“Immediacy” and “intimacy” feel pretty well commodified at this point, and not just by the big money but by the indies and the artists too; get your DV cam in close on a human face being banally human, with hyper-ambient sound design, and we’ll respond with Pavlovian pleasure at how well you’ve captured the Real. Frownland treads this territory too, but it’s leavened by an air of nostalgia that’s less retro than willfully anachronistic. Its 100%-celluloid material and Method-ish performances may be just more convention, but all these conventions counterbalance to create something new. This is probably because Bronstein handles them with an affection and a nastiness that save each other from the platitudes they’ve become in the hands of hacks and auteurs alike.

The comedy/drama of discomfort may have evolved into pure rhythm indifferent to its own content, but Frownland forgoes this evolution, and the result is a film whose effect is cumulative and energy-based. Though it’s not energy in the sense of that knee-jerk equation (noted by Andrew Tracy in Cinemascope, issue #29) whereby "cinema" equals "kineticism" and vice versa, it’s energy nonetheless, unqualifiable and all the more exciting for it. It’s hard to imagine Frownland having this effect outside of the cinema, without an audience responding to a projected film image by filling the theatre with multiple, contradictory responses, by no means unanimous but still communal. That this can only be achieved over a sustained duration, through the spending of time with people whom you would most likely avoid in real life, speaks not just to the film’s style and process but to its ethical underpinnings as well. Its energy manifests itself—onscreen and in the audience—variously as cringes, flinches, and outbursts of laughter. Whether all this twitchery is genuine or physiological is in this case a meaningless distinction; it’s necessary.