Always Now:

An Interview with Ephraim Asili

By Erik Luers

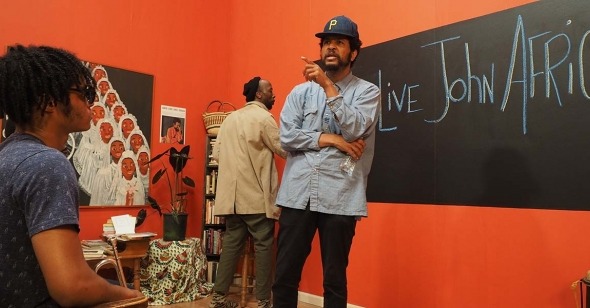

A feature debut indebted to—and in conversation with—its spiritual ancestors, Ephraim Asili’s The Inheritance shows a narrative filmmaker working to expand the cinematic form. Set in a West Philadelphia activist commune over the summer of 2019, The Inheritance invokes the present moment while offering a rigorously researched and fluid appreciation for its revolutionary history.

After the passing of his grandmother, a young man in his early twenties inherits a West Philadelphia row house and begins a makeshift collective that promotes the work of Black revolutionaries. His reason for doing so is geographically influenced: in 1985, the Philadelphia Police Department was ordered to bomb the shared row house of MOVE, a Black separatist group led by John Africa. The attack left eleven people dead. In solidarity with MOVE, the film’s present-day commune is stocked with famous books and records, Nixon-era movie posters (Ivan Dixon’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door and Ralph Bakshi’s Coonskin are but two of the titles on display), and a drum set, growing to become a place for educational discovery and dispute. House rules include but are not limited to “no shoes indoors” and “no stealing of other members’ items from the community fridge.” Tensions and arguments arise from there.

In addition to his work as a filmmaker, Asili, a native son of the “City of Brotherly Love,” serves as Assistant Professor of Film and Electronic Arts at Bard College, and his artistic output is, at least in part, a visual syllabus. Shirley Chisholm, Angela Davis, Ruby Dee, Sonia Sanchez, Alice Walker, Malcolm X, and various other intellectual artists and activists make their presence known throughout The Inheritance, their voices heard even when not visible on-screen. Explicitly, unabashedly invoking Jean-Luc Godard’s 1967 study of student revolutionaries, La Chinoise, Asili’s film is cluttered with history in each of its physical forms. In the rare instance of the viewer being taken outside the home, our attention is directed toward the murals of Black community members adorning the sides of apartment buildings and playgrounds. The Inheritance is American history played out in the present.

A few days before The Inheritance was set to be virtually released via Grasshopper Film, I hopped on Zoom to chat with Asili about his professional and personal struggles to get the film made.

Read more at Reverse Shot on The Inheritance by Devika Girish.

Reverse Shot: I wanted to ask about how your interest in cinema was formed through the work of specific composers. I know the film work of Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and Barry White were important to you, and I’m wondering if it’s accurate to say that music was your gateway into cinephilia?

Ephraim Asili: The way your question was phrased makes me think about it in a different light actually. When I was a kid, the films that were marketed to young African Americans were first and foremost marketed via their soundtracks. Studios didn't spend their television advertising dollars on those types of films, so if they had an action film to promote, they would put some hip-hop songs on the soundtrack, and that's how people would end up becoming aware of and going to see Juice or Boyz n the Hood or Above the Rim. That was very much a thing back then. And it actually goes even further back, all the way to Melvin Van Peebles and how he defined his Sweet Sweetback's Baadasssss Song as an opera. He was the first person to do that, to really use the soundtrack to promote a film. Sweet Sweetback was a big influence on me, even if I wasn’t a film buff at the time. My friends and I (back in our activist days) would casually watch the film and thought of it as a “bad-ass” movie. Only later did I learn about Melvin Van Peebles as a filmmaker, and how he formed a relationship between musical composition and the moving image. I feel like that was almost intuitive to my filmmaking too. I grew up listening to Wu-Tang Clan and other groups that were cinematic in their lyrics, and if you couldn’t appreciate it [as cinema], what were you getting out of it? These were the influences that embedded the idea of sound and composition as potential images or, in some cases, actual images, in my mind.

I was more of a musician and DJ before I found my way into film, and music was an easy way for me to understand certain concepts around the moving image. While it’s something that I've been consciously trying to develop since the beginning of my career, I only discovered this about myself over time.

RS: Have you found that being a college professor also influences your approach to filmmaking? The Inheritance is so intertextual and bibliographic in its pursuits that I wondered if that was the professor part of you providing a kind of syllabus for the viewer.

EA: I try not to separate those roles out too much. Half of the cast of The Inheritance is comprised of former students of mine—“former” meaning they graduated that May and were on my set by June. That’s also true of some of the assistants behind the camera. When I started writing The Inheritance, I had just started teaching and was invigorated to suddenly have groups of young, smart people who were serious about the world around them. Being a professor has provided me with access to how younger people think. I'm in my early forties now and my students remind me of the activism I was participating in in my twenties. As I was writing the film, I was thinking about some of my students and things I had heard them say at some point on campus. It’s a world that many filmmakers who don't teach don't have access to.

If a new film comes out on Friday, by the following Monday I can ask my students, "Well, did you all see the film? What did you think of it?" Their presence is a big influence on my work, and I try to make sure that it's not something I’m just taking from them and giving nothing back. I’m incorporating these people into my work and hopefully I’m finding them gainful employment and getting their foot in the door. Being a filmmaker and being a teacher are related. In the past when I’ve told myself, “Okay, I’ll spend a few months working [on my next film] and then I'm going to shift gears [to my teaching job],” it begins to feel artificial or inorganic. That’s why I try to treat it all as one big practice that incorporates both.

RS: While the five short films that make up The Diaspora Suite—shot between 2010 and 2017—are essential for newcomers of your work, the concluding entry, Fluid Frontiers, feels like a thematic prelude or a run-up to The Inheritance. Do you view it that way, as a kind of precursor to your first feature?

EA: I do. With each film in The Diaspora Suite, I was trying to work out a different technical or theoretical idea in my practice. By the time I got to Fluid Frontiers, the one thing I hadn't tackled was synchronous sound, and the reason I hadn't tried it was due to my being intimidated by the Arriflex SR2 camera and having to load film into the magazine. People are generally dishonest and say, "Oh, I just didn’t want to do it,” but the reality is that everyone is afraid to load the mag. I was like, “You know what? If other people can do it, I'm going to force myself to learn how to do it and shoot the film. If I can learn how to do that, then that opens up the possibilities for long-form films and the ability to include dialogue in my work.” That’s what I wanted to get out of Fluid Frontiers, in a technical sense. The thematic content involving Detroit’s Broadside Press and the poetry in the film was really what resonated with me as I made it. As I was shooting the film, I began thinking about making a feature. I didn’t have a script at this point, but I had a few ideas that I was able to explore a bit in Fluid Frontiers and wanted to dive deeper into.

While each of the people in Fluid Frontiers are people that I just casually met, at the same time, even in our brief interactions, we were able to arrive at a formative space that was very intriguing. That’s when I began thinking about screen acting, like, “Wow, what if someone is a ‘professional’ at doing this? Then we can play with these interactions even further.” Professional acting, or portraying emotion on screen, is like a raw material of filmmaking that I hadn't fully explored by that point in my career, and so I wanted to have actors really embody the ideas I was attempting to get at. It felt like an intriguing thing to attempt.

RS: You had initially planned to film The Inheritance in an actual West Philadelphia row house akin to the one MOVE inhabited in the early 1980s. Because of budget constraints, rather than shoot on location, you moved the shoot to a more controlled environment: a black box studio in Troy, New York. What was life like for you in the interim, in between attempting to shoot on location and having to rework the production demands to shoot in an interior setting?

EA: No one has ever asked me that question in quite that way. That window of time was probably the darkest window in my entire life. I had been writing the script and thought I had been doing fairly well with it. I was even being asked by a few production companies what I was working on, but when I would tell them about The Inheritance’s plot, no one was interested. On top of that, in that same window of time, weirdly enough, my sister, out of the blue, passed away. Her son (my nephew) came to live with me and so now I was looking after him while writing a script centered around this idea of loss. And then a few months after that, my mother unexpectedly passed away as well.

Here I was, having lost my mother and my sister, watching after my nephew as I continued to work on a half-written script that no one would give me money for.

RS: Do you have other siblings?

EA: I have a brother who is still with us, thankfully. Anyway, that’s what was happening at the time. I felt like I was losing control and so I put down the script for some time. I then thought back to when I began writing the script and how the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute provided me with a grant. They believed in the notes I had already written, and they told me several times, "If you should ever want to use our set, we'll pay for the actors, we'll build the sets, etc." And I kept saying no, because I insisted on shooting on-location in Philadelphia. But after I experienced so much loss in my personal life, things changed and I needed to just accept something that was being offered to me as a gift. I went back to EMPAC and said, "You know what? I've changed my mind. Let's do it." And we shot the film there.

RS: I wanted to ask about the set you constructed. The walls are painted in these strong reds and mustard yellows and there’s a theatrical component in the design as well. As presented on 16mm, the warm colors pop in a very alluring way. What was your design process like?

EA: It’s a great example of the way photography and design and plot and acting are all configured together in my head. The set design is integral to that as well. Knowing that I was going to be shooting on a set and that it had the potential to be depicted in a very realistic way, I decided to push in the opposite direction, knowing that since there would be documentary elements to the film, I could mess with the narrative elements a bit. The set allowed me to play with the degree of reality involved and I toggled between making the set look more and less theatrical. The set’s relationship to how it was being photographed was crucial.

RS: Speaking of the film’s documentary elements, you include several instances of archival footage. In a conversation you had with Garrett Bradley at last year’s New York Film Festival, you mentioned that you use archival material to bring in and include the ancestors who otherwise cannot be present, either because they're not here anymore or for other reasons. I found that to be a striking way to describe the use of archival footage, refocusing it in the present tense.

EA: Yeah, and our conditioning to archival footage is not oriented in that way, right? We view it as, “Oh, I'm looking at information from the past." Look, there's nothing wrong with thinking that way, but it's very boring to me. When I pull up footage of Shirley Chisholm—as I do in The Inheritance—that no one else has used, I’m activating that footage by sharing it with others. When I think in a non-Western context and put an African worldview on how I use the archival, it's like I'm calling forth that ancestor. We're blessed to have the technology that enables that relationship to happen. Rather than try to channel it through my “being,” it's something that I can actually search for and access.

Thinking in a Western context, this is just stuff stored in a box in a place called an “archive.” However, that's not where I'm coming from and that's not how I’m working with this footage. There’s a delicacy to how you place archival in a film and how it interacts with other elements of the story. I wanted to create a feeling that the footage is acting on the actors in the film, albeit in a very loose way. That’s also true of some of the objects in the film that are a part of my personal collection.

As we’re having this conversation, there’s a Milford Graves record behind me, and I like to think that when I take his record out and play it, I can hear him drumming and, to some degree, I am invoking the spirit of that person. I imagine he would agree. That’s how I think about these items.

RS: You shot the film in 2019?

EA: Yes.

RS: After its world premiere at the 2020 Toronto Film Festival, you said you felt that, as a society we're only now catching up to the politics of the film. How have you seen the public’s perception change? A lot has obviously transpired in the country and around the world since you went into production two years ago.

EA: First, to go further back to the production itself, one of the first scenes we shot was the meeting scene that takes place in the middle section. We shot a take, and I wasn't totally satisfied and was trying to figure out what the issue was. Everyone seemed too relaxed, and I was like, "No, no, there's an urgency to this meeting that has to be felt in the meeting itself." They would ask why, and we had a discussion and were able to work out what each of their characters’ motivations were.

This is something that would come up not only with our actors but also from various people unconnected to the film. I would be asked, “Why this film? Why now?" Well, by the time the film was released, people stopped asking, ‘Why this film? Why now?’" There were no longer any questions about the relationship between revolutionaries acting out in the streets and their weird obsession with domesticity. Once we began screening the film for the public, we were suddenly in a pandemic that has totally disrupted everybody's domestic lives and, in a sense, how we negotiate space is very politicized. And then there was the continuous murdering of young Black people by the police which, while sadly nothing new, was given new context with the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

Their murders [and the subsequent public outcry] have provided a viewer’s openness to the film now where it’s not like, “Why this subject? What axe is this filmmaker trying to grind?” Now it’s more along the lines of, “We continuously live through this throughout our lives, and we’re asking ourselves these kinds of questions all the time." When I was making the film, I didn't expect it to be such a mainstream topic of discussion, but these issues have been everywhere in the headlines over the past few months.

RS: How has it been to screen the film virtually? A physical space for exhibition is incredibly important, of course, but given recent global circumstances, we’ve had to adjust. One positive to come from that is that your film is available to more people and at a much faster rate. Have you enjoyed that experience? Have you been dismayed by it?

EA: Even if it’s been hard at times, I like to remind myself that more people are seeing my film now than would have ever been able to if film exhibition hadn’t shifted to an all-virtual setting. Some of the press coverage also reflects that, the accessibility the film has been given. When the film began its festival run in Toronto, it was one of only fifty features selected for that year’s edition. All of the critical attention is only going to go to these fifty films, and you don't have to compete with overlapping screening times or running across town from one theater to another. In many ways, I guess it's been beneficial.

The part where that isn’t the case is in not being granted direct audience interaction and the passionate conversations and learning that comes from being in a theater together. That’s been a little frustrating, but I’ve done these virtual events a number of times now and it’s been okay for the most part. I was really upset at first, upset for myself for not being able to do certain things, but the film has been doing very well regardless. I have to keep in mind that while I may get frustrated, there are many other people that don't have nearly as many opportunities as I do to share their work. I'm in a really good place, all in all. Hopefully the pandemic ends soon, but what are you going to do?