Two Cents 2020: Part One

In giving out this year's Reverse Shot awards for the best and the less-best of 2020, we somehow managed to go over our limit of honors, even without the privilege of going to the movies. Maybe it was the derangement of these past months, but we somehow had a lot to say, and a lot to remind you to see—or stay away from. So here is part one of our, as always, rigorously superfluous addendum to our Best of the Year list.

Best Godard Remix: The Inheritance

During this seemingly endless pandemic, one way to mark the passage of time is through the discourses that cycle through “Film Twitter.” There are some that recur like seasons, setting off streams of inanities and think pieces. There’s always some hubbub about sex in cinema; there’s some or other variant of corporate bootlicking cloaked in statements like “let people like things”; and then there’s Godard-bashing: swift, 280-character dismissals of a complex and influential 70-year career. What bothers me about this latter trend is not just its reductivism—Godard, like it or not, is a part of film history, and denouncements like “overrated” and “problematic” are poor ways to reckon with history—but that there exist writers and artists out there who’ve engaged far more intelligently and critically with the filmmaker’s legacy, producing rich, envelope-pushing works that provoke thought and not just outrage.

A recent and particularly striking example: Ephraim Asili’s The Inheritance. A superbly inventive film about a collective of young African American artists and activists sharing a house in West Philadelphia, The Inheritance tips its hat to La Chinoise—the poster of the 1968 film is one of the prominent elements of Asili’s pop-art mise-en-scène—while transposing to a contemporary Black radical context (and thus fundamentally scrambling) Godard’s premise of young revolutionaries grappling naively with ideology and its aesthetics. Like the best of homages and the best of critiques, The Inheritance is a bit of both; Asili has described it with a musical analogue: a “remix.”

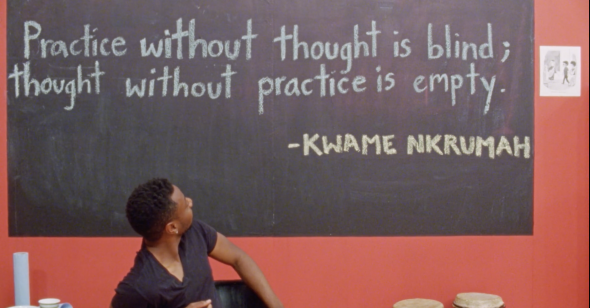

I hesitate to dwell too much on Godard, because The Inheritance is a work of thrilling formal and political originality whose lineage extends in many other directions. The narrative derives from Asili’s own experiences in a Black Marxist collective, and it wryly captures the negotiations that undergird communal life: from whether or not to wear shoes inside the house to how to open its resources to the wider community. The film concerns itself with the ideals of the Black Arts Movement both implicitly, with a form shaped by the search for political articulation, and explicitly, featuring performances by artists like Sonia Sanchez. And Asili weaves in the history of the MOVE organization, a Black liberation group in Philly that was bombed by the FBI in 1985. Members of MOVE appear in documentary portions in the film, discussing their story, which is illustrated by archival footage. In stitching a patchwork of these histories with Godard’s film, Asili articulates a history of both revolutionary politics and political cinema that extends beyond moments of rupture, and across boundaries of time and culture. Political objects, like Mao’s Little Red Book, become accessories in La Chinoise—accoutrements of a fetishized revolution. The Inheritance turns La Chinoise itself into one such accoutrement of the living archive that is the shared house, alongside Julius K. Nyerere’s Essays on Socialism, a “Chisholm for President” T-shirt, Kwame Nkrumah quotes written in chalk, and innumerable vinyl records. What appears cynical in Godard’s film—ideas flattened into things—is generative in The Inheritance. History takes up space, and by forcing the characters to confront and live amidst its material realities, it threads itself into their everyday. —Devika Girish

Worst Idea: Bad Hair

One of the year’s most ill-advised cinema experiments belongs to Justin Simien, who decided to make a horror film about Black women’s hair: specifically, a cursed weave that turns a diffident young assistant into a murderous succubus. Specious, rather uninteresting approximations about race abound in Simien’s most famous credits to date—the film and later Netflix series Dear White People—so unsurprisingly Bad Hair contains, in addition to goofy camerawork and offensive imagery (one Black woman is hung when her weave loops into a noose around her neck), a clumsy and patronizing social missive that categorically maps violence and trauma onto Black women’s relationship with their hair. Chris Rock’s equally condescending 2009 documentary Good Hair at least pretends to entertain the possibility that Black hairstyles possess unique potential for artistry and creativity, far away from either a white or, as happens, paternalistic gaze. Nonetheless, every time, what prevails over complexity is the base, myopic presumption that Black women are particularly beholden to a colonial mentality, a premise steeped in misogynoir that betrays the way Black men benefit from pathologizing Black women. —Kelli Weston

“We Live in a Society” Award: Promising Young Woman

Two promising young women wind up dead by the end of Promising Young Woman. But rest assured, the cops have definitely got it handled. As satisfying as it is to see a Hollywood film take such an openly misandrist approach, the revelation that all men (even the sweet and goofy ones named Bo) are pigs isn’t exactly a revolutionary takeaway. Director Emerald Fennell leans into the feminist rallying cries du jour with a kind of focus group-dictated eye towards confrontation; the result feels disturbingly like the product of a Twitter-generated checklist of satisfying beats masquerading as provocative ones. Where is the friction, ambiguity, and perversity? Carey Mulligan plays Cassandra Thomas, an ex-med student possessed by rage, and determined to exact some kind of righteous damage—if only psychological—on the kinds of men who abuse and rape with impunity. The film plays out essentially as an escalating series of gotcha moments, building up Cassandra with directionless girlboss triumphs that feel cheap and naggingly empty at their core. We’re left wondering who this super-genius avenging angel actually is beyond her trauma, which completely defines her personality. It’s not just hopeless and self-defeating as a portrait of female empowerment, it’s practically Joker-esque in its flailing insistence of its own social relevance. —Beatrice Loayza

Most Honest About Algorithms and Brain Worms: Spree

It’s bitterly ironic that the film that most adeptly critiques the problems with social media and technology was lost in the digital morass of streaming at home; it also fucking sucks. Riffing on Eugene Ionesco’s “The Lesson,” Spree follows Kurt Kunkle (Joe Keery), a streamer who finally goes viral by recording himself killing passengers while driving for a rideshare app. Although this premise sounds like two trends thrown together, it evinces the logic of someone like Kurt, who has been completely warped by digital culture—specifically the perversity created by algorithms that endeavor to keep users on their platform as long as possible—and the inherently pathetic mechanics of shit that actually goes viral. Director Eugene Kotlyarenko adopts the aesthetic vernacular of those who relentlessly document their lives—how they frame themselves, how they dress, the inane intonation of address, the low-content of their one-sided conversations with their audience—but infuses them with a cinematic sensibility and piquant sense of humor, a Hi, Mom! for our times. (At one point, the “real” footage of multiple streams create a visual misdirection worthy of the oft-abused adjective “Hitchcockian.”) Kotlyarenko, who, like De Palma, punches from a further-left position than polite mainstream liberalism, begins with caricature (the people Kurt kills are pretty awful) and slowly pierces the surface of his mobile slasher, ending up with something that’s far messier, sadder, and realer than you’d anticipate. Similarly, a high-speed police chase on a freeway goes from a thrilling genre exercise where Kurt drives against traffic to a chilling statement on how the subaltern are treated when he drives beneath the freeway, crushing the homeless in their tents screaming about their worthlessness and lack of social media presence.

Jesse (Sasheer Zamata, who finally has a role worthy of her talents), the stand-up comedian Kurt eventually faces off with, has similar but vastly different tech problems: she wrestles with the pressure to digitally present both her personal life and stage persona, while attempting to dodge stereotypes supposedly enlightened white people online have no problem attributing to attractive black women (i.e.: “slay kween,” that gif of Viola Davis shaking her head and picking up her purse, etc.). In the end, she too is blessed and cursed with viral fame, and gains a fanbase that’s much larger but no less heartfelt than Kurt’s; both of them get what they wanted in the worst way possible. Spree is unsparing in its view of new and old media (there’s a delicious zing on New Yorker profiles, if you’re into that thing), fame, the surveillance state, and of our daily, self-imposed submission to Silicon Valley technocrats. It also refuses an easily tweeted “take” while fluently speaking the language of online, where everything’s a joke until it’s not. —Violet Lucca

Party of the Century: The Year of the Discovery

A kind of Lovers Rock avant la lettre, Luis López Carrasco’s brilliant debut feature, El futuro (2013), was set at a raucous house party in 1982 on the eve of a landslide election of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party. His most recent film, The Year of the Discovery, deals with a moment exactly a decade later, and is set entirely in an actual working-class bar in the Murcian city of Cartagena—a dense, nicotine-stained atmosphere contrasting sharply with the jubilant ambience of 1992, which saw the celebration of the quincentenary of Columbus’s voyage from Spain to The New World and the Summer Olympics in Barcelona. As in the previous film, López Carrasco constructs both a complex formal and temporal gambit and a rich materialist (counter)discourse on Spain’s recent history as seen from below. Through bifurcated images, shot in the fuzzy colors of Hi-8 videotape, the film compiles documentary interviews into a novelistic portrait of a cast of characters—nearly fifty in total—whose recollections of daily life, labor, and struggle generate resonances between the encroaching neoliberalization of the 1990s, the economic crisis of 2008, and the struggle as it continues into the present. —Leo Goldsmith

Best TV: Dau

Early on in the pandemic, filmmaker-madman Ilya Khrzhanovsky began to issue films in his Dau series online at a rate of about one per week, rentable for just a few dollars. The project—a several-thousand-strong battalion of cast and crew members inhabiting and performing on a massive live set that was documented nonstop for several years—alleges to tell the life story of Soviet Nobel laureate physicist Lev Landau. Yet over the course of 14 films, ranging in length from standard feature to hours-long epics, following dozens of major characters across decades, a larger portrait of the idealistic rise and exhausted collapse of Soviet Russia emerges. Tuning into the latest release each weekend presented the opportunity to dip back into a group of familiar characters, experience the progression of central storylines or witness key events from entirely different perspectives. Two-hander chamber drama DAU. Nora Mother gives way to the epic madness of DAU. Degeneration. DAU. New Man reframes crucial happenings in Degeneration while DAU. Katya Tanya or DAU. String Theory splinter off to focus on characters glimpsed but left subsidiary in other films. Each new film explodes the world outwards. Calling Dau TV here isn’t meant to invoke the tiring “is it cinema?” debate. But if the things we call “TV” revolve in some ways around questions of repetition, continuation, and interval viewing, Dau could be considered the among the best the small screen had to offer in 2020. —Jeff Reichert

Best Ensemble: Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets

Key to the deceptive vérité of Bill and Turner Ross’s Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets, an explosive, elegiac documentary-narrative hybrid about the last day and long night of a shuttering Vegas dive bar named the Roaring ’20s, is the film’s collection of relaxed, affecting, and symbiotic performances from real-life topers and toilers playing dramatized versions of themselves. Presiding over the loosely structured, largely improvised chaos is the sozzled, scraggly vagrant rendered with fascinating introspection, occasional volatility, and not an ounce of self-pity by Michael Martin, an old hand of the New Orleans stage. But no amount of training is required to make the nonprofessional performers who surround him any more compelling and distinctive. Shay Walker, seen too briefly as the mother in Benh Zeitlin’s Wendy, inspires instant devotion to her raspy, circumspect barmaid, already envisioning life beyond last call. Pam Harper deftly teeters between the roles of blowsy, tits-flashing blowhard and hand-clasping mother hen, while Rikki Redd exudes the unbothered self-possession of a barroom luminary; the latter’s enlivening lip sync of Aretha Franklin’s defiant “My Way” reclaims that tune away from recent Trumpian associations. And few screen actors have cut deeper in recent years than Bruce Hadnot, whose heartbreaking Black Vietnam veteran is a walking wound of a man, swilling down cold ones into a body long drained of its hopes yet thick with disappointments that can barely be articulated before the tears begin to fall. Like any year, 2020 saw laborious turns from thespians who should know better. But their vessel-bursting efforts pale in comparison to the pained, pleased, and experience-marked faces on display in Bloody Nose, in which no person is merely an extra, but the sum total of a life lived and now expressed with all the honesty that can be spared. —Matthew Eng

Best Pig: Gunda

Worst Pig: Sam Spruell in Mangrove

Best Risk-Taker: Her Socialist Smile

Director and professor John Gianvito has taken a noteworthy risk in the midst of an unceasing documentary boom. Indeed, Her Socialist Smile affords viewers access to Helen Keller’s passions—her under-discussed leftist politic, her literary bite, her willingness to be ornery for the right cause—all while avoiding go-to genre conventions: dramatizations, redundant use of sparse archival materials, and talking heads galore. Instead, Gianvito showcases Keller’s political prowess through filmic experiences that bear proximity to hearing and visual impairment. Aside from two of the only known recordings of her voice, Keller’s words largely appear in a white sans serif typeface on a black background. Walls of text linger without the anticipated score or voiceover companions; to truly hear and see Keller, and reap the staggering benefits, the able-bodied viewer must put in work. Gianvito’s risk certainly pays off, rendering the documentary a challenge and reward to viewers. To know Keller, one needn’t hear her, or even hear commentary from those versed in her biography. Sight and sound, though considered vital to cinema, aren’t always formidable metrics for identifying and uplifting a woman who was ravenous for life. —Sarah Fonseca

Best Valediction: Labyrinth of Cinema

Following Nobuhiko Obayashi’s death in April 2020, Labyrinth of Cinema took on a meaningful aura as it traversed last year’s festival circuit. A dark room and big screen would have certainly intensified Obayashi’s colorful phantasmagoria, but most who saw Labyrinth likely viewed it on a laptop or a home television. What a gift. During a year when the act of visiting a movie theater became glossed by a powerful yearning, what better than a film in which Obayashi’s trademark surrealism allows characters (and, by extension, viewers) to pass through the mesh of the screen and enter the film world itself? To watch this final film is a full-bodied experience of both mourning and celebrating an artist whose energetic, category-evading body of work pulsates with historical criticality. —Katherine Connell

Hood Ornament Prize: The Rental and Relic

In August, months into the first wave of the pandemic that had shuttered movie theaters across New York, my husband and my bubble buddies and I piled into a rental car and headed upstate for some open-air delights. Foremost among them was the not-inconsiderable pleasure of attending a drive-in double feature in Warwick. Not having seen any feature films projected onto screens since the fateful weekend in March when we took in both The Invisible Man at the multiplex and Woman in the Dunes at BAM, we acknowledged that it didn’t really matter what they were going to show. It could have been two hours of Fancy Feast commercials; it could have been a new cut of Cinderella Man; it could have been Drive. We’d have been rapt no matter what. So the IFC Midnight double feature was starting from an enviable position. And so it went. Four words that would have normally made me put the car in reverse—Dave Franco’s The Rental—heralded 88 minutes of “tight” and “economical” thriller material that had me shrugging and nodding in pleasure, while I forgave the second feature, Natalie Erika James’s Relic, its queasy Alzheimer’s-as-haunted-house metaphor for reminding me how marvelous a pitch-dark screen can look, especially when one can just make out its borders below a nearly full moon. The night was warm but not oppressive, the sky was clear, and the movies were competent. We drove home with the joy of cinema buzzing in our ears. After months of being locked up in our respective homes, trying to make movies happen again—as comfort, as sustenance, as communal activities—it was a pleasant reminder that for movies to really work on you, you need to be tiny, decentered, a small face in a crowd. —Michael Koresky

Best Character Names: Atarrabi and Mikelats in Atarrabi and Mikelats

Worst Character Name: Gatsby Welles in A Rainy Day in New York

Most Unhinged: Russell Crowe in Unhinged

The phrase “Russell Crowe road rage movie” ping-ponged inside my brain like the last Tic Tac. It was the beautifully simple log line that instantly cinched Unhinged as a potential balm for the bored—and angry—lockdown doldrums. To see the swollen actor (himself famed for violent, occasionally telephone-wielding outbursts in the late ’90s and early 2000s) go ham on some unlucky bad drivers seemed like it could provide catharsis via vicarious fury release. But it was catharsis repeatedly deferred, as the pandemic forced a hedge-betting Solstice Studios—who hoped the film would tempt audiences back to cinemas—to keep delaying release, from May to July to August, when it was finally released in theaters a full two months before arriving on VOD. I’d since moved on, but of course watched anyway, and though the film doesn’t live up to such an epic rollout, it delivers on its promise of Russell Crowe doing road rage. His Tom Cooper is a divorced, recently unemployed, bitter member of the silent majority who in Crowe’s paws is a sweaty, snorting, teeth-grinding oversized meatball of resentment. He’s scariest when attempting semi-politeness, as when he growlingly educates Rachel (Caren Pistorius), the single mother whose honking kickstarts the film-long showdown, on the etiquette of the mini-honk “courtesy tap.” Crowe, allegedly in padded costumes (he was likely inhabiting corpulent Roger Ailes in Showtime’s The Loudest Voice around the same time), is a thick mass of menace in an almost Noah-worthy beard and a blood-flecked blue button-up, out of which his poundage practically begs to pop. Derrick Borte’s film is largely a series of adequately choreographed car chases around greater New Orleans (held up in the middle by the memorable diner butchering of a divorce lawyer played by Jimmi Simpson). Bland Rachel makes a mostly uninteresting sole target, but Crowe’s shameless, wrathful emoting borders on greatness. —Justin Stewart

Most Numbing: On the Rocks

I had meant to write a more extensive review of this one, but frankly each time I sat down to eke out a few more words a wave of disinterest came over me. I imagine that’s how Sofia Coppola felt while writing the script: floating between pleasantly cozy boredom and willful indifference. Rashida Jones—a charisma vacuum—is a good fit for such sleepy, milquetoast material, which traces Coppola avatar Laura as she learns the valuable life lesson that when you’re filthy rich, the worst thing you can do is be a bore. At the beginning, she’s taunted by an empty word doc, yet the stakes are low because she’s been given an advance. Uninspired and unmotivated, her mind—as blank as her draft—wanders. Bill Murray steps in as her dad to fill the pages with misogynist maxims that bring both excitement and distress into Laura’s life. Might her hubby be two-timing her? (When Laura chuckles at Chris Rock on the tube, delivering a bit from Never Scared, his 2004 stand-up special—“Nobody tells you that once you get married, you will never fuck again”—one wonders if Rock’s insights are meant to register as timeless or trite.) Laura is a character who lacks the depth and interiority to meaningfully scrutinize her own unhappiness. Dad sends her on a wild-goose chase, when all she had to do was ask her husband if he’s cheating—and voila, the writer’s block is solved and her autonomy regained. Meanwhile Coppola gestures at potentially compelling elements (the NYPD’s cushy treatment of her father, Laura’s mixed-race background, how the arbitrary value of art mirrors the characters’ privileged existence), only to lose interest with such little compunction. This year, Force Majeure was given the Hollywood treatment (i.e., lobotomy) with Downhill, yet the threat of a Toni Erdmann remake carries significantly more weight. You can imagine my horror when I realized it had already landed. —BL

Worst Update: Rebecca

Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again...and it was dull as fuck. Daphne du Maurier famously wished she had been a boy, so successive generations of boys have obliged her by adapting her best works: Hitchcock (thrice), Roeg, Gore Vidal, Welles (whose Campbell Soup radio players’ presentation of Rebecca closed with a live broadcast of a transatlantic phone conversation between Welles and du Maurier herself), as well as countless television “showrunners” (as I understand writers are now called). And now, for no reason, comes Ben Wheatley with a pot of Netflix cash, indulging in a brassy, classy “sure thing” adaptation of Rebecca which looks like every other goose-shit-green and mustard-yellow prestige production you’ve seen in the last two years and contributes precisely nothing to Daphne du Maurier’s tragic account of the identification of a woman. Lily James, whose ubiquitous presence on our screens has the flavor of intense vanilla, is good casting as the bang ordinary second Mrs. De Winter, who grabs her chance at romance while in service of a monstrously unkind Ann Dowd in Monte Carlo. Her plight, once she arrives at Manderley Castle, is to be set upon by all comers, when all she wanted was to prolong her passionate love story with Armie Hammer’s intoxicating Maxim (whose dark blond three-piece suit is apparently so iconic that he has to wear it every day). He was ravenous when whisking her off to the Plage du Larvotto for a champagne picnic, but now they’re hitched, he barely acknowledges her presence on the few occasions he’s even around. One genuinely creepy sequence with Jane Lapotaire as Maxim's demented old mother recoiling at James's presence, reminds us of Wheatley's skill (and waning appetite) for the truly unsettling. Chief among the second Mrs. De Winter's tormentors is the legendary literary hate figure of Mrs. Danvers, who is played here as a Kristin Scott Thomas-like character by Kristin Scott Thomas. But the real threat in Rebecca is the mythic Sphinx (and Lamia) Rebecca herself and her torture of this poor replacement from beyond the grave. This classic gothic story places psychology (jealousy, paranoia) in coalition with metaphysics, while mirroring du Maurier’s own anxieties of failing to live up to the expectations of her own gender. But none of this interests Ben Wheatley, so it follows that nothing in his pitiful film interests us. —Julien Allen

Worst Mythmaking: Hillbilly Elegy

I have been thinking about writing a memoir—perhaps the first of several volumes—titled Bohemie Elegy. It’s not set in the Czech Republic, but rather in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, a medium-sized midwestern city that has an opera, North America’s largest cereal plant, and was blighted by the loss of nice blue-collar jobs during the ’80s and ’90s. The narrative would retell the guidance I learned from my Czech grandfather, Milo, who would lecture my ear off every time we got in a car about the values of hard work, equality, and reading. (A perpetually cranky non-drinker, Grandpa would sit in his favorite chair in the parlor and complain about the conservatism of the Cedar Rapids Gazette and refer to Iowa’s then Governor Terry Branstead as “Terry Braindead.”) It would also explore the gifts imparted by the rest of my dysfunctional family, like my mother (who spent most of her life in ineffectual, public mental health facilities) and my aunt (an overweight public-school teacher who’d lecture me about the importance of feminism and guilt me about academic performance). Bohemie Elegy would provide key insights to a state that flipped from Obama to Trump, and show that middle westerners actually know you’re supposed to dress up for job interviews—like what, we don’t have television and movies there!? (I drank chardonnay from boxes and from bottles in old Ioway!) In addition to sketching a loving yet honest portrait of my family, I would pathologize any negative parts of my upbringing and culture in order to push my socialist politics. Hopefully I could get a job with some big, high-paying socialist think tank after publication. Those exist, right?

Like every unhappy family, every middle-sized Midwestern city is unhappy in its own way—Cedar Rapids, Iowa, is not the same as Middleton, Ohio, and to pretend otherwise is foolery. As Lyz Lens (a liberal columnist for the Cedar Rapids Gazette) notes in the introduction to her excellent book God Land: A Story of Faith, Loss, and Renewal, the midwest is a place full of contradictions, yet is supposedly so normal that it resists characterization or a coherent identity. J.D. Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy, and its subsequent film adaptation, wants to do a lot of world-building for terrified coastal elites. Both properties not only err in claiming it is the Rosetta Stone of flyover state Trump voters—you know, because the only people who live in these states are conservative whites, right?—but by arguing that these angry honkies’ problems are of their own making, specifically a problem of “Scots-Irish” culture, which is distinct from the WASPs of the northeast. The sub-Wonder Years narration gestures toward the long, slow decay of (white) America: “Whatever better life my grandparents were chasing, they never got it … something was missing, maybe hope.” But it also saves most of the ideological punching down for J.D.’s sassy, swearing grandma. If you tear away the putty from Glenn Close’s face, there’s only bootstraps ideology beneath: “Two years from now those idiots will be on food stamps or in jail,” Mamaw hisses when little J.D. falls in with the wrong crowd. While the makeup isn’t as janky as the trailer made it seem, there’s an obsession with it that beggars belief—Hillbilly Elegy’s end credits show side-by-side comparisons of the real people with the actors who just portrayed them.

It’s deeply unfortunate that Hollywood’s rare foray into the midwest—one where Reganomics, NAFTA, the opioid crisis, and the 2008 financial crisis have taken their toll, and no assistance is coming—is, above all else, a series of mewling pleas for Oscar gold. There seems to be nothing else thanthe supposed fidelity to the original, as the film fails to touch on what it actually means to be poor: the waiting, the wanting, being told no, the shame, the wish to be that intangible normal everyone else’s family has. Despite spending so much time with J.D. and his struggle to achieve his boring-ass dreams, the film offers no clear idea of what success is. Do we all have to go to Yale with a bunch of snobs and become an “entrepreneur,” even though we don’t know which fork these pricks use for salad? Does getting a TI-83 calculator from your grandma and buckling down in middle school only work for white people? (His Indian-American girlfriend, Usha, played by Freida Pinto, who literally phones in her performance, draws a laughable parallel between the immigrant experience and J.D.’s journey.) In a year where the abyss of poverty has so greatly expanded—precisely because state and national governments have at once failed to be “big” (provide sufficient financial assistance to citizens) and been too big (hamstringing small businesses with ineffectual restrictions that have only prolonged the pandemic)—being served this bootstraps myth, that one where we are actually masters of our own destiny, is especially revolting. —VL

Most Pleasing Junk: The Invisible Man

Least Pleasant Hunk: Martin Eden

The “Thrill Isn’t Gone” Award: The Grand Bizarre

It remains a seemingly unshakeable part of our collective consciousness—call it the persistence of our puritan inheritance—that emotion, sensation, or other byproducts of our bodies are widely seen as obstructions to thought and not the very things that plunge us most into it. In cinema, and experimental practice in particular, this attack on visual pleasure has led to a league of execrable (and frankly boring) filmmaking and theorizing that seems to mistake an ascetic world for an emancipated one. Thank goodness for Jodie Mack. The Grand Bizarre, Mack’s 60-minute, stop-motion barrage of patterned textiles and electro bops, may very well earn the label of “structural film,” its play between difference and repetition being central to its aesthetic strategy, but not once do we sense that its self-reflexive investigation into the limits of our perception is done out of any sort of malice (as though we should be castigated for not seeing or hearing in a manner that transcends the conditions of the body). It’s no coincidence that watching The Grand Bizarre has been likened to attending a dance party—a comparison that captures the film’s inviting tone, if not its precise kind of sensory overload. Indeed, we aren’t so much attuned to its rhythms as completely out of step with them. You might very well feel as though you’ve hit the wall of the mathematical sublime: confronted with a sensory mass so large it defies all extensive forms of measurement, our minds grasp this flurry of images as an abstract whole even as our imagination fails to comprehend the density of its parts. —Josh Cabrita

The “Show Not Tell” Award: The Assistant

The film industry is not the only system that demands change in the way women are treated. All spheres of society require drastic improvements. If Kitty Green’s The Assistant is “just” one of the most recent in a long line of entertainment products dramatizing #metoo, it is perhaps the first of these that takes revenge on a sociocultural sector that, more than any other, has been under scrutiny since the outbreak of the Weinstein revelations. Piling up in the printer like a crowd of silenced victims ready to speak up, the actress portraits xeroxed by Jane—played by Julia Garner, our Virgil in Green’s descent into modern hell—highlight cinema’s “original sin”: that women are judged on appearance. And yet, as cinema is firstly a visual medium, it can narrate facts directly, without falling into the prosaic fallibility of words. If we could always tell by showing, how much harder would it be to prove us wrong? —Clara Miranda Scherffig

Best Structuring Absences: Yourself and Yours

Made in 2016, the year after Right Now, Wrong Then inaugurated his ongoing cycle of films with Kim Min-hee, Hong Sang-soo’s Yourself and Yours, released stateside in 2020, almost seems haunted by the lack of her. It is a thrillingly free-floating film, flitting between the two halves of a couple, including a woman who keeps denying her identity for unknown reasons. With this set of structural gaps, Hong is free to include all manner of details and interactions that latch in the mind as strongly as the comedy of remarriage that forms its center: an unexpected reunion of schoolfriends, the disrobing of a mannequin, a random makgeolli-sodden encounter. Hong’s universes are always porous and open to possibility, but the holes deliberately created in preserving the film's mystery allow for both these accoutrements and an unexpected, miraculous reconciliation, predicated on a series of persona shifts and acceptances that could not have been achieved without the film’s central absence of fixed identities. —Ryan Swen

Most Lived-In: Nicole Beharie in Miss Juneteenth

This past year featured plenty of resourceful actresses tackling overburdened mothers in films legitimately concerned about their plights, from Hong Chau’s formidable single mom in Driveways to Maren Eggert’s mourning widow in I Was at Home, But… to the masterful Essie Davis as the parent of a dying teen in Babyteeth. Chief among this roster is Nicole Beharie, whose central performance in Channing Godfrey Peoples’s Miss Juneteenth is a revelation, a long-overdue fulfillment of all the promise inherent in the actress’s smaller but no less skillful turns in films like Shame, 42, and Monsters and Men. As Turquoise, a onetime Fort Worth pageant queen-turned-barmaid pushing her skeptical daughter towards the same crown, the Julliard-trained Beharie digs so deeply into this role that she renders herself indistinguishable from the film’s love-starved, dog-tired heroine. Beharie has eyes of tremendous, soul-searching depth, and it’s astonishing to watch the actress turn her gaze inward as Turquoise silently second-guesses her indomitable drive or else replays a past in which she could feel her significance first-hand. Beharie shows Turquoise entertaining many options—professional and personal—while making one wonder what it is that Turquoise truly seeks in this life. Even as Turquoise chafes against the patronization of those eager to make her the sum of her missteps, Beharie appears utterly at home in the character, carrying the movie to its joyful finish. Her recent Gotham Awards win notwithstanding, Beharie seems unlikely to rack up the prizes she deserves in the coming months. Even so, Miss Juneteenth should be all the incentive directors require to hand Beharie more parts on a par with her excellence. —ME

Best Throwback: Sertânia

Those who think the Modernist film so common in the ’60s and ’70s is dead ought to track down Sertânia, the latest film by octogenarian Geraldo Sarno, whose contributions to Brazilian documentary and the depiction of Brazil’s impoverished Northeast still await widespread Western discovery. Sertânia’s black-and-white is as sharp as any Glauber Rocha film, and its narrative—both fatalistic and metaphysical in its depiction of a dying man, Antão, recalling his journey from São Paulo to his Northeastern childhood home—is as intellectually dense as any film of the era. But Sertânia is no mere throwback: Antão’s odyssey is also an exploration of history and nationhood that speaks as sharply about the present as it does about its past. —Forrest Cardamenis

Best Old White Male: "Old White Male" in The Lobby

Being yelled at by an old white man isn’t typically my idea of entertainment, yet some of the most fun I had last year at the movies (or what remained of them) could be described as just that. In Heinz Emigholz’s The Lobby, the director’s frequent collaborator and screen surrogate, John Erdman, stars as “Old White Male”: a nondescript, curmudgeonly figure who unleashes a relentless monologue about mortality and its discontents (death, sex, religion, capitalism, Nazism, shit, and so on) while seated in the glossy lobbies of various upscale buildings in Buenos Aires. All-knowing as only those of his ilk are authorized to be in our culture, Old White Male addresses the viewer directly, lecturing, chastising, and even preempting our responses, but when he invites us to look into the mirror with him, he sees only himself. This central illusion of cinema becomes in the hands of Emigholz and Erdman a clever, comedic little puzzle box of solipsism. Old White Male reaches for universal knowledge but encounters at every turn the circular limits of his own mind. And so he claims conquest over the ultimate unknown: death. “I am way ahead of you,” he says, “because I am dying, and I know it.” —DG

Grimmest Beginning: Collective

Happiest Ending: Days