The World of Never-Were and Almost-Was

An Interview with Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson on The Forbidden Room

by Eric Hynes

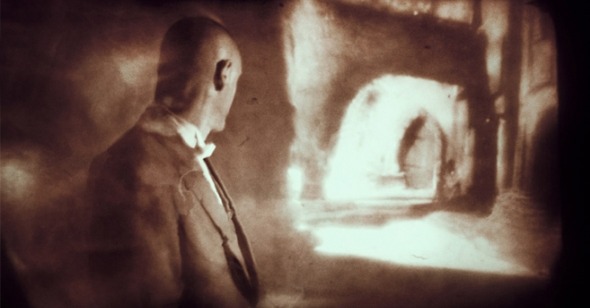

The screening for Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson’s The Forbidden Room that I attended at the Sundance Film Festival in January almost immediately became legendary, and counts among my most memorable viewing experiences of recent years. From an opening title sequence comprised of a seemingly infinite variation of fonts, textures, tones, and styles, directly into a direct-address monologue on “How to Take a Bath,” complete with silken bathrobes and fleshy indulgences, to a doomed submarine narrative in which flapjacks provide emergency oxygen, to the weirdly heroic exploits of a smitten woodsman, the film takes off at flickering speed and never lets up. Ostensibly comprised of the remains—or the rumors, or just the titles—of “lost” films, Hollywood and otherwise, The Forbidden Room indeed comes across more like a room, a giant holding cell for ricocheting narratives, than as a single narrative. One story leads to, blends with, morphs into, and invades another, seemingly without rhyme or mercy. Meanwhile the surface of the picture blends and morphs as well, changing color and quality like a deep-fried dream. Or nightmare. Or phantasmagoric fish tank. Or Lava Lamp.

I’d estimate that about a third of the audience left the Library Theater during the first hour of the screening—perhaps some were unfamiliar with Maddin’s work, which has always been rich with tangents, perverse asides, and bemused subplots, perhaps others couldn’t switch to Maddin’s gear after digesting Meru or Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, and perhaps some just couldn’t keep riding the bull as it kicked and snorted. You lose the thread. You lose any sense of time. You spend an ungodly amount of it watching Mathieu Amalric struggling to de-pants a corpse. But the benefits of weathering Maddin and Johnson’s storm are considerable. Once acclimated to the notion that no established thread will ever satisfyingly be tied up in the end, you’re freed to exult in the momentary—and to register the gravity behind such a structural assertion, that all that’s lost can only be briefly summoned or glimpsed or guessed at before it fades back away. Then, after completely giving up any expectation of resolution, the opened Russian nesting dolls of the narrative actually do start to come together, culminating in a prolonged, orgiastic, near-simultaneous finale for many of the stories. It’s exhausting, even irritating at times. But it’s also electric cinema. Looking around the room after the conclusion of The Forbidden Room, I saw looks of bewilderment, joy, and post-hypnosis disorientation, often on the same faces. For a few minutes it felt as if the lost stories might continue off-screen, warping around the streets of Park City. Or maybe I just wanted them to.

As the filmmakers told me in the below conversation, conducted during the New York Film Festival, the movie took much longer to complete than other Maddin projects, owing in part to the voluminous research entailed in collating hundreds of lost films. They also embarked on a unique filming process, which involved shooting in public studios at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, at a rate of one day per film, with cameos from the likes of Geraldine Chaplin, Charlotte Rampling, and Louis Negin, a Maddin regular who’s kind of Larry “Bud” Melman reincarnated as a mugging thespian. Their talk tended to emulate their storytelling, winding and detouring and volleying, punctuated by laughter.

Reverse Shot: Since this is your first credited collaboration, I’d love to know what your working relationship was like, in terms of who took the lead on what and when.

Guy Maddin: Often we do exactly the same thing. Like screenwriting. Although within screenwriting, Evan is like the conscience. And I’m kind of like the…

Evan Johnson: Unbridled id. I’m the superego, and the movie is… the ego? I don’t know my Freudian…

GM: In the writing room Evan will just tell me to stop fucking the taxidermy. Or something like that, and tell me why it was wrong. And then by the end of the day our script is fine and it feels like the perfect mixture of unbridled and not insensitive to everybody. We each work about the same, depending on the story. Sometimes these stories came out in one chunk. Literally sometimes a dream just makes its way to the page. And other times they’re really labored over. In the writing room we had this guy Bob Kotyk, who also wrote with us. And then John Ashbery wrote the framing device—the host of the show—by himself as a monologue, his adaptation of Dwain Esper’s lost How to Take a Bath. Then, even though Evan and I are both directors, I’m the one who yells action and cut. I shoot, so does the DP, so there’s two cameras going all at once. But Evan is never more than one or two seconds away from me. Because I sort of have the script in my head, and then I just double-check. Often we’ve got to rewrite on the fly, when we’re running out of time, so we do it together, as writers and directors. But because he’s also, I guess, the postproduction director, he can suggest solutions that can be achieved later on the fly.

EJ: The much-maligned “We’ll fix in it post.” People hate that phrase but…

GM: People would make fun of it all the time, because when you’re pressed for time on the set, in the old analog days, you’d say, “We’ll fix it in post”—but then the fix was kind of patchy. But now in the digital era you don’t just fix it but actually make it in post. And the movie’s very cooked. That’s the right word for it.

EJ: Yeah, it’s pretty cooked. But we wouldn’t have had anything without the footage, obviously. So I think too much has been made of the cookedness of it.

GM: We still had performances, and some of it’s not that cooked at all—it’s just color-timed. It was a real thrill for me to watch Evan take raw, ugly, suicidally depressing footage and just remove colors from it, which all of a sudden transformed it. Even though it was still digital you suddenly saw it as chemicals. What was removed first, to make that standard, two-strip Technicolor look?

EJ: You just sort of channel all the color information through only two colors, a bluish and orangeish.

GM: That’s really exciting. All of a sudden it looks like the product of volatile and really picky chemicals. And then you just kept creating new palettes that wouldn’t really be possible out of simple emulsions. Because those chemicals that create those colors don’t make up film stock. So you were creating emulsions out of new elements on the periodic table. It was kind of fun. So the breakdown was that we’re co-creators of both the feature film and its companion piece on the Internet, an interactive called Séances. We’re just two hemispheres of the same wildly inefficient brain.

EJ: It wasn’t just cooking the footage that we had to do afterwards. The movie looks messy but it has a firm spine. It was about finding some kind of coherent order for everything, though it may not appear to be coherent.

GM: We both read Raymond Roussel’s nesting fictions. This French writer from the twenties and thirties who wrote poetry, short stories, novels, and plays. Everything is nestings within nestings within nestings. You really analyzed it—I read it once and got a great thrill out of it. It was through John Ashbery that I discovered Raymond Roussel—he had translated him into English. I don’t know how you discovered him.

EJ: A Jodorowsky interview.

GM: And then you really took over at that point. Because one of his job duties was to cheer me up. I’m used to films taking about a year, but this one took four or five. And so sometimes he would just lead by example. He was really sorting out the structure of the film. I mean I was there.

EJ: We did that together.

GM: We did do it together.

EJ: We did what screenwriters dream of doing. Which is writing stuff on index cards, putting them on the wall and moving them around.

GM: Yeah my living room just had all these titles of lost movies, and we were organizing them into a basic three-act structure. But I will go on record as saying there were times where I was just really flagging. I wasn’t used to things taking this long. My personal life seemed to be falling apart. And what few decisions I was making were being made from a horizontal position.

EJ: Yeah, you would nap a lot.

GM: Sometimes supine. Sometimes prostrate.

EJ: You’d mix it up!

GM: That’s right. “I’m going to try prostrate today, Evan. See if that helps.”

RS: Watching it a second time through, it was easier to recognize the spine holding it all together. The experience of watching a first time can feel quite unmooring.

GM: I’m sure. There are attention span issues. You pay attention to one thing more than another.

EJ: And it’s kind of tiring.

RS: That’s definitely part of it, but that’s also what I found kind of thrilling. Feeling a little run around and knocked about the nested, runaway narrative. The film is drunk on story, but it’s story as an element among other things, rather than the sole driving force. It’s like story is another surface for you to play with.

EJ: That’s also another thing inspired by Raymond Roussel. His stories are almost pure narrative framework. And then the content itself is mysteriously absent or meaningless. We weren’t trying to have meaningless content—we wanted it to be psychologically true, or true to our lives, or funny.

GM: That’s where we differed wildly from it.

EJ: But there’s still something about the complexity of a structure with a sort of emptiness at the middle. The complexity of the structure suggests that you’re going to find something important right at the end of the reel—the secret. And the key is that you don’t. I mean, that’s a classic technique, a common theme in films that are about desire, or are about wish fulfillment. Say Tarkovsky’s Stalker, where they end up in The Room that’s going to fulfill their desires, but when they get there and they’re like, I don’t know, I don’t have any desires, I guess, or my desires are incoherent.

GM: It’s all effort. It’s all about getting there.

RS: This quality was present in your earlier films, Guy, but you’ve taken it a bit further in The Forbidden Room.

GM: I’m not going to touch any of my old movies, but if I could I would shorten them all. Tighten them, make them more brisk, make it so they don’t overstay their welcomes so much. But this one has a whole different set of criteria. We could have trimmed this down easily to 75 minutes, just by removing seven stories or something. But we wanted it to be overwhelming. We wanted it to feel like on the surface there was a real narrative tempest, that the viewer had just barely survived being drowned at sea, and then is washed up on another shore, panting. So it’s tricky, because it’s hard to guess when too much is just the right amount of too much.

EJ: It kind of needed to overwhelm the viewer. I don’t know about you, but I feel overwhelmed and overstimulated by the modern world. I realize that sounds pathetic.

GM: Too many donut flavors for one thing. Take a look at these things. [Stands up and reaches across the table to open a half-empty box of donuts of various colors and shapes.] It’s unbelievable. Some of these aren’t even donuts. There’s like sweet meats in them, things like that. Anyway, yes, overstimulated.

EJ: I guess there’s something mildly neurologically personal about the experience. As you always say, while we were researching the lost films that we based all these stories on, we were overwhelmed with an excess of research material, of stories that we liked. And then the more we tried to become demographically or ethnically responsible about all of the world’s lost stories, there was too much. Then you look at your bookshelves and you have a hundred or a thousand books that you haven’t read and that you’ve always wanted to read. The sense of being overwhelmed by story is just something that was on our minds, self-consciously.

GM: And yet there were so many that I would have love to have filmed. We just didn’t have the energy or the will anymore. But there were so many cool ones that we had on our list that we could have gone on and on about.

RS: And yet there’s that added tension between what exists and what you’re inventing. You’re telling lost stories but you’re also making them up.

GM: We had to be the mediums through which these almost spirit-like, haunting, once-weres were hovering around, and they had to come through us. And they came through our eyes and our aesthetics. So they ended up rhyming with each other in many ways, because we often had to supply plots where only a very highly suggestive title existed. And so, we were like mediums at a paranormal séance, the whole presentation is spoken in our voices. What we chose, what we didn’t choose, what interested us, what we riffed on, sometimes what we just dreamt or felt, or hated, or wanted to strangle…

RS: Did you come up with full arcs for these, only to shoot a sliver of them?

EJ: Often, yes. Sometimes the full arc is somewhat present in The Forbidden Room, but sometimes it’s just a sliver, an elliptical sliver.

GM: Each one is written to be a fifteen or twenty-minute long movie. Shot in one day. And sometimes a movie was based on more than one lost movie. As if a spirit showed up to be shot who, you know, brought some buddies. Some other lost films. “You mind if my buddies come in to be filmed today?” “Oh, okay.” Some lost Bolivian film coming in. Or a lost Cuban film. “Okay, come on in, you’re lost.”

RS: You talked about your being the medium for these lost films, but to take it a step further, it also seems like this film is a medium for film itself. Because you’re not working in film but the film is comprised of old film ideas and affectations—it’s an expression of film.

GM: That’s true. Digital is a medium for all these film spirits. Or the memory of film, the emulsions rattling around in our heads. Certainly the source material for almost everything is film. We were briefly going to allow cathode ray hauntings into it, because I was really intrigued by the lost Dumont TV network that America once had. You know, The Honeymooners was on it. I think Jackie Gleason invented the Kinescope or something to record The Honeymooners. But when that network went down, no one was recording the shows, so all sorts of really intriguing stuff was lost.

EJ: Isn’t there a World Series that’s lost?

GM: Games three and four of the 1974 World Series were erased by NBC, I think. I watched those games. We were going to, in a Kammerspiel—something set in a living room, maybe an infidelity Kammerspiel—we were going to have someone throwing pick off tosses to first base, with a foot on the couch while catching it, with, like, a dowager maiden aunt diving back on these close plays. Because I remember Herb Washington was the first designated pinch runner in baseball history—Charlie Finley had hired him to be only a pinch runner. He was the world’s fastest runner, the Usain Bolt of his time, and Charlie Finley put him in a baseball uniform even though he’d never played baseball before. And he famously got picked off in the World Series—he was leading off too far, and fastest or not, he got picked off. And that’s lost. I wanted to get that into one of our movies. But we just had so much to shoot. But it would have been nice to have, say, Geraldine Chaplin play Herb Washington and diving back to first.

RS: Do the actors get it? Are they into what you’re doing?

GM: They seem to have a riot, frankly. With the odd exception, the odd meltdown.

RS: It’s almost a kind of perversion, what you’re doing. Taking these incredible legends of cinema and…

GM: Shooting them in public? We were, literally, in Paris. You could watch from the stage level but you could also watch from above, on a kind of a balcony with a railing. And every now and then gum wrappers or half-chewed mouthfuls of baguette would sort of drop down onto the stage. Or just dandruff.

EJ: In case we needed snow.

GM: “Yeah, cut the snow! Oh, ok, never mind.” Some old bibliophile up there scratching his bald head or something.

RS: So Charlotte Rampling is down there being snowed on by dandruff?

EJ: She was a good sport.

GM: She was there for four days. She’s barely in The Forbidden Room but she’s there for four lost film adaptations in Séances. She’s in some western. Is that a Howard Hawks western?

EJ: No, William Wellman. But it wasn’t a Wellman western. We made it a western.

GM: We were starting to mash up. It was Ladies of the Mob. It was a gangster picture but we made it into a western with Udo Kier. But then wardrobe in Paris couldn’t come up with a cowboy hat.

EJ: Now it’s like a sequined cowboy hat. And he’s got like sequins on his vest as well. He’s not the most masculine cowboy.

RS: Does film matter any more to what you do? Is it just the idea? Is film like Obi-Wan Kenobi to you, no longer material but stronger as a spirit?

GM: At the risk of angering Christopher Nolan or Quentin Tarantino, it doesn’t matter to me much. I did bring a Super-8 camera with me to New York to make little sketches. But it’s just—in the history of the world, and in the history of art, mediums change. You keep moving forward and every now and then art looks back over its shoulder, acknowledges what’s behind it, in one fashion or another.

RS: Yet it’s so filmic what you’re doing.

GM: Yeah, maybe just the way some photographers make painterly stuff and some painters make photographic stuff. It’s all just an option. It’s a budget issue as well.

EJ: I like watching film, better [than other formats] probably. But I’ve never even touched film. I grew up with camcorders and stuff like that—I’m comfortable with digital grain, stuff that looks hideous to some people.

RS: And as you described in terms of the color removal process, the movie isn’t necessarily emulative of film—it’s inventing colors and qualities.

EJ: We were trying to blend the worlds together.

GM: It’s taking whatever we can, and using it.