New Corridors:

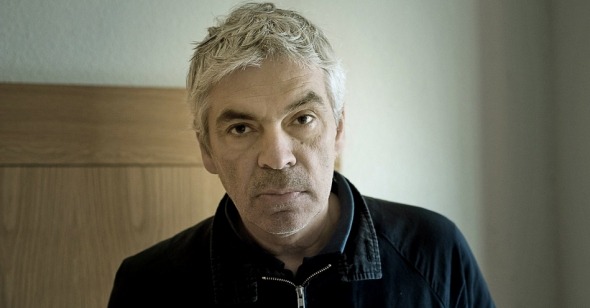

An Interview with Pedro Costa

By Daniel Witkin

Since the turn of the millennium, Pedro Costa’s has been one of the least compromising voices in contemporary cinema. For many cinephiles, In Vanda’s Room (2000) and Colossal Youth (2006) signaled nothing less than a possible new direction for 21st-century cinema. Boldly (and controversially) combining documentary and fictional modes, his films have simultaneously been documents of a very specific time and place, bold experiments with the possibilities of digital cinematography, and idiosyncratic cinematic poetry. His new film, Horse Money, is at once another leap forward and a return into the medium’s past, drawing on 1940s genre flicks to achieve a tense psychological urgency. I had the good fortune to sit down with Costa at the Film Society of Lincoln Center, where he programmed a series of films to play alongside a complete retrospective of his work. In line with the director’s omnivorous cultural background, he touched upon his would-be collaborator, the late Gil-Scott Heron, the Beatles, and the legacy of punk.

Reverse Shot: What can you tell me about the photographs by Jacob Riis that open the film? What attracted you to them?

Pedro Costa: I’ve known his photography since the eighties. In film, photography, and music, I’ve always been more interested in what you might call the realistic— photographers of reality, documentary, or simple photo-reporters. So he’s in that category. He’s more than a photographer—he’s a researcher and anthropologist. He wrote and talked about his work. He lived in the places he worked. It’s almost filmmaking.

RS: So why did you choose you put them in Horse Money?

PC: It felt right. When I had the film almost completely edited, I already had the idea of adding a set of ten to twelve photos, but I didn’t know where. Seeing the musical sequence as a series of interior portraits of people in the neighborhood, I thought that it could be an echo or rhyme if I placed the photographs in the beginning, showing almost the same people with silence and with music.

RS: In your previous films you shot a lot inside homes in Fontainhas. This seemed to inform a lot of your process, both in terms of the intimacy it gave you as well as a certain freedom from the pressures of a more traditional production model. How did you adjust to shooting in these various institutional spaces, including hospitals and offices?

PC: We were shooting in public spaces, but they were vacant, empty, deserted, abandoned. Everything is sort of like a leftover of something else. The hospital is not really a hospital, it’s just what’s left. The factory is abandoned. All the streets are very empty of humans, of life. They’re more like catacombs. I think that’s because the places where the characters in the other films lived disappeared. The old neighborhood was demolished. The new neighborhood is nonexistent. It’s a no man’s land. It’s a fictional land, less real than the other films.

RS: Can you tell me a bit about the setting of the film? What made you want to center the action around a mental institution?

PC: The mental and physical state of Ventura and the rest of the characters, the signs they show, the trembling, the shaking, the vagueness, the shivering, the soft-spoken voices, are all a reflection of what’s been happening since the beginning, which is that they’re losing everything. It’s almost a state of war—we call it austerity, we call it economic crisis, we call it war almost. So they’re losing everything and they have nothing left, not even a house, not even a neighborhood, not even a roof. So we don’t have sets to shoot in. We almost don’t have a wardrobe—that’s why Ventura’s in pajamas. I’m joking, but everything is a way of showing the human condition, as we used to call it.

RS: Could you tell me a bit about your artistic collaboration with Ventura? You’ve mentioned that while making In Vanda’s Room you would do dozens of takes per shot. Is this something that you’re also able to do with Ventura?

PC: Yes. We had practiced before on Colossal Youth, so we had worked a lot—lots of takes and lots of rehearsals. He needs the rehearsals and the repetition, and I need it too, because we don’t work with a screenplay, we just have some notes. So we have to find our narrative, we have to find our building, our house. He’s used to work. He used to be a bricklayer, and he always says that a film is a joke compared to building a house brick by brick.

It varies from sequence to sequence. In some sequences, he does more reacting to other actors who are more prominent, such as Vitalina. But that long, long 25-minute sequence inside an elevator took us more than three months to shoot, and it was tough for him and for all of us. We had to find the sequence, the gestures, the tone of voice, everything. It was a very difficult scene because he was really acting. It’s almost like a superhero movie, like Marvel. He was acting with a puppet, with no one, with a kind of monster, a virtual creature, so he had to force himself to believe that this creature was real.

RS: Music is a big part of your work in general, but it seems particularly central in Horse Money. You’ve mentioned that Gil Scott-Heron was going to be involved before he died. How much did his brief involvement impact your conception of the film? Do you think it had an effect on the finished product?

PC: Well, I hope something remained because I really loved him. I always loved his music, and his lyrics, and his attitude. Not just the music, but his position. He was a true citizen, reacting to what was happening in his community. I’m very moved by this kind of artist, who is not confined to the arts. Art needs something else—if it was just a film or a record or a painting, it would be useless. It has to involve a kind of attitude towards this, towards society.

So I hope something remains, but I had just three meetings with him. He wrote something, but I never got it because he died suddenly and nothing was found, then I lost contact with his people. But I think that in Vitalina’s melody and chant, there’s something from him. I think that the polyphony of voices in the elevator is close to what we thought of doing, which was something much more abstract. It was going to be musical and a sort of prayer, but a cantata, but…

RS: A psalm?

PC: A rap? It would be probably have been sung by Gil himself, or Ventura, or just lots of other voices. I don’t know but it would be a kind of long poem or prayer, probably much more fragmented.

RS: You mentioned that you were a musician before coming to cinema? How has this affected your work?

PC: I wasn’t really a musician—I played guitar in a band. It was ’78–’79; everybody had a guitar. It was that punk rock moment, everyone was trying to do something without knowing how to play or how to paint. It was a very vibrant moment, very political and energetic—incomparable to today, I’m sure. What was fantastic for me and my generation was that we were living everything at the same time and with the same intensity, without priorities or differences—a photograph by Frank or Walker Evans would have the exact same power for us as a film by Godard or John Ford or a song by Wire, the Clash, or Gang of Four. Everything was exactly the same kind of lived experience. It was in the streets, it was palpable. It was not consuming things in record shops; it was different.

RS: During the musical scene in Horse Money, I was reminded of the very stylized shots of peasants in Dovzhenko’s Earth that precede the hero’s death. In previous interviews, you’ve alluded to the influence of the Russian silent filmmakers on your work. Can you tell me more about this?

PC: They are companions. That’s what it’s called, companionship. I thought about a lot of scenes in a lot of films, Russian or German. The Russians are closer to documentary or realism or whatever you want to call it.

Those films and filmmakers are constantly with me. They were very important for structuring my thoughts, my eyes and ears and everything. They are very, very strong editors: Eisenstein, Vertov, Dovzhenko. The montage of attractions us something that counted a lot for us and for every serious filmmaker.

RS: I found the editing in Horse Money to be more immediately apparent than in your previous films. At a Q&A following Trás-os-Montes, you mentioned how much you considered AntĂłnio ReĂs and Margarida Cordeiro to be “real editors.” What did you mean by this? How did you approach this aspect of filmmaking?

PC: Well, I hope all of them are edited. In this one, the scenes are less built on one shot. The scenes themselves vary a lot. The elevator is faster than the rest. With Vitalina, it slows down. The other films are more contemplative, but this one is faster. The models were B-movies, thrillers, detective movies. The idea was not to let the viewer think too much, but to get to the next shot quickly.

RS: Clearly, the memory of Fontainhas plays a big role in Horse Money. Though it’s never seen, the neighborhood becomes a sort of structuring absence. Do you think that nostalgia has a place in your films?

PC: Melancholy does, but that’s a different feeling. Ventura, I think, is melancholic. All of them are, but they’re not nostalgic for something that’s no more. I think that all of them would say that they prefer the old house, the old neighborhood, the old style of living, the old traditions, the old everything, but they are not nostalgic. They don’t have it in them. But they always were and they always will be melancholic—it’s in their music and their beings. Being melancholic is more about longing for something that we’re almost sure will never happen, it’s more towards the future, more pessimistic. Fatalism is very common among Cape Verdeans and Portuguese, even in our poetry. Pessoa said everything there is to say about that. He was a master of pessimistic melancholia.

RS: Do you feel that you’ve become more pessimistic over time?

PC: Yeah. It’s like the Beatles’ song that says, “It’s getting better all the time.” We’re going back to the dark ages. I mean the real dark ages, because the Middle Ages were very spiritual compared to this absurdity that we are living today. Very dark, very dark.

The film seems modeled on the horror film and the thriller. We shot in catacombs. But it’s really just a reflection of what’s happening in some parts of my city in a certain community. But that community is about 90 percent of humanity. It’s at least 50 percent of this country, maybe more.

RS: Significantly more.

PC: It’s Europe, it’s Asia, it’s South America, it’s North America.

RS: So that covers the “Money,” why “Horse”?

PC: That’s the hard part for me to talk about. I can only talk about the money. Ventura had this horse called money, which was the idea of a better future for him, a kind of son, a beach alone in the islands. Then, like he says in the film, his horse was eaten by vultures.

RS: Do you think that Money is a good name for a horse?

PC: Yeah, why not? I like the title because it confuses, it divides, it’s strangely beautiful. Horses are okay, but I like having money in the title. It’s not just for them, the rich guys. We can also have money in our work, even if we don’t actually have it.