Match Point

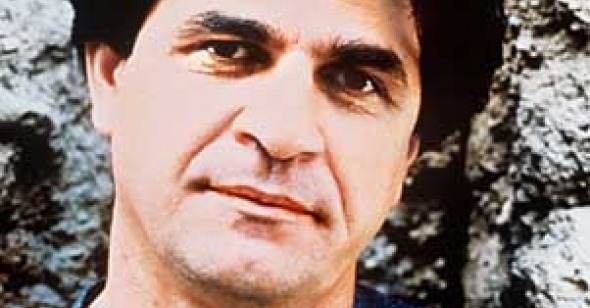

An Interview with Jafar Panahi

By Chris Wisniewski

In one of the year’s best films so far, a group of young women “dress as men and surreptitiously sneak their way into Tehran’s Azadi Stadium to watch a World Cup qualifying match between Iran and Bahrain. These women aren’t (consciously) feminists, and, more profoundly, their defiance isn’t even explicitly political. These women are soccer fans. They want to watch the match because they want to root for Iran and desire nothing more than to participate in this small act of nationalistic fandom, and to cheer for the country they call home, though it officially excludes them from this aspect of public life.”

RS: Congratulations on yet another wonderful movie. I’ve been a fan of all of your movies, and it’s great to see such engaged and impressive work so consistently.

JP: Thank you. I have made a resolution for myself that I should only make good movies, and so, even though it takes me three years to make a movie now, I’m really just trying to make the best career I can.

RS: Offside addresses many of the same recurring themes in a lot of your other work, but it also has a hook that makes it accessible for audiences. Since it’s structured around the central soccer game, the film has a clear narrative trajectory and a satisfying payoff that feels kind of new compared to The Circle or The Mirror. What drew you to this particular story at this point in your career?

JP: You know, I live in this society, and all my subjects come from things I see around me and things that affect me personally. And this also came from something that happened to me personally. I wanted to go see a soccer game a few years ago, and my daughter, who was twelve years old at the time, wanted to go with me. I said, “Obviously, they’re not going to let you in so why bother?” She said, “I’m just curious.” My daughter wasn’t even a soccer fan, but she was curious to see what she was being kept from seeing. So we went to the stadium, and predictably at the gate, we weren’t allowed in. I went in, and my daughter said, “Don’t worry about me; I’ll do something.” And then ten minutes later, all of a sudden, my daughter joined me. And I was surprised and said, “How did you get in?” She said, “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.” And I said, “Well, what did you do exactly?” and my daughter refused to say. If she resorted to a ploy or a trick, what was it exactly? Even to this day, I don’t know how she got in. But this gave me the impetus for making a movie about this subject.

RS: One of the most unexpected aspects of the film is the rapport that develops between the girls and the soldiers. They engage in quite a bit of friendly debate. How much of that was written into the screenplay, and how much was improvised by the actors? How did those relationships evolve?

JP: In Iran, army service is mandatory when you turn 18. So the conscripts are not really representative of the government. They’re just a part of the Iranian society, and as such, they agree with some rules and regulations and disagree with some other rules. So they can be very much direct with the people, and it’s easy for them to sympathize with people. The girls are also quite understanding of the problems of the soldiers. That’s why one of them who sneaks away comes back, because she realizes there may be consequences for the soldiers if she does run away. Both the soldiers and the girls are trapped within social restrictions and the kind of discrimination that is exposed in the movie affects all of them and has consequences throughout society. That’s why, when there are protest rallies regarding women’s rights, you see the presence of Iranian men as well. It shows that they sympathize with women and join their voices to that contest.

I can tell you that only about fifty percent of the screenplay was in place when we started shooting the film. Just half of the script was prepared because we didn’t know the outcome of the game, and we knew the second half of the script would depend on the outcome of the game. And also, as we were shooting the film, we realized that there was more room for the soldiers, and we should give them a little more room to project their personalities, their opinions, their views. So gradually, we made their presence a little more prominent.

RS: The film is somewhat unassuming but also technically impressive. The takes are extremely long and well orchestrated, and the game is really integrated into the narrative. Can you talk about the shooting process? How much visual planning did you do? When you started shooting every day, did you know exactly what you wanted to accomplish in each of your takes?

JP: The narrative in this movie is embedded in a documentary manner. We knew that there were certain shots that we had to shoot on the day of the game that would give the whole movie that documentary feel and make it plausible for the audience. When I started making this movie, I realized that I was sort of confined, and I wouldn’t be able to have the same sort of full control that I had over my other movies. It wasn’t possible to stage the kind of mise-en-scène you see in my other movies, because I knew I had to make it have that documentary feel. At the same time, I knew this was a kind of filmmaking approach that was important to me, and I wanted to get away from what I’d done before. So it was a question of negotiating the circumstances with the elements of style I wanted to preserve in the movie.

I had a lot of ideas when I was shooting and staging the scenes, but at the same time, I wasn’t completely sold on them, and I knew that things would happen, and I had to be prepared for changes to whatever ideas I had and just go with the flow. To give you an example, there’s a scene early in the movie where the girl buys a ticket and a poster to get into the stadium. That was obviously something that we wanted to do. But as she’s walking toward the stadium, somebody out of the blue just knocks her hat off, and she looks around. At the same time, she looks at me outside of the shot, because that person knocking off her hat wasn’t a part of our script. That was just something that would happen in any crowd situation. So when she looked at me, I immediately had to think, “Well, what is my next move?” so I told her to just run away, and that’s what she did. So this was a spontaneous thing that happened in that shot, but it dictated to me what I needed to do in the second shot, which was to pick her up running already and just continue with her running to somewhere else. So the shots that I just mentioned were shot on the same day that the game was being played.

RS: To return to something that you had mentioned earlier: All of your films in some way come back to this theme of social limitations, whether they happen to be gender or class. Your characters have to keep negotiating this idea of the limits that are placed upon them. I wonder, with that in mind: Would you consider yourself to be an activist filmmaker?

JP: No, on the contrary, I see myself as a socially committed filmmaker, not someone with a political agenda. I’m well aware that all our social problems are somewhat politically related, and they come from political problems within the country, but I don’t want that to affect my movies and therefore I don’t make political movies. Because I realize that when you make a political movie, it’s like you’re putting an expiration date on it. And making a great political movie puts a distance between me and cinema, and forces me to give up the sort of power that I’d like to discuss. I’m interested in the humanistic outlook. To protect that, and to protect that in my movies. That’s why you don’t see people who are entirely evil or people who are like angels, really good or really bad people in my movies. And even when you have a person coming from a military background, they’ll have a human quality.

RS: It seems very timely for American audiences to see a film that shows the diversity of opinion and the real social debates that do happen in Iran, given the current political and military tensions. Especially in relation to what you were saying about not making movies to intervene in a specific political moment, how do you feel about the American release of the film coming at a time when it does seem especially relevant?

JP: My movies reflect my own beliefs, and every one of my movies are about those personal beliefs of mine and how the films are received in America or other countries—I really don’t have much control over that. I firmly believe that our people are civilized people and educated and intelligent enough to start to fight for their own rights, and to satisfy their own needs. Any changes in my country will be because of the people’s own recognition, the people’s own knowledge, and how they want to rectify any situation. I’m dead opposed to any power or foreign country invading Iran and changing the situation through military means. We’ve seen through example the consequences of this sort of move, which is nothing but destruction. The kind of dialogue you hear in my movie between the girls and the soldiers in nothing new in our society. It’s almost a daily dialogue that you hear in the streets, in the cabs, on the buses, and everywhere you go. These are the things that people talk about in our country. Unfortunately, there are two forces that refuse to believe that people themselves are intelligent enough to take care of their own problems: one is the current ruling government in Iran and the other one is the foreign power that because of their own interests, is trying to use the situation in Iran as a pretext to justify military action. And the two individuals who symbolize these two forces are Ahmadinejad in Iran and George Bush in America.

RS: The movie gives a sense of the similarities between the political dialogue in our society and the political dialogue that happens in Iran. And I hope that audiences who see this film realize that any ruling party doesn’t necessarily speak for everyone within a given society.

JP: I hope the people in America share your views and feel the same way. And hopefully, finally, these powers will come to their senses.