Text of Light No. 5

Here and Elsewhere: The Cinema of Vincent Barré and Pierre Creton

By Jordan Cronk

Earlier this year at the Play-Doc International Film Festival in Tui, Galicia, I met Pierre Creton and Vincent Barré, partners in art and life whose films I had belatedly discovered when Creton’s A Prince premiered as part of the 2023 Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes. Together they were at Play-Doc to present their latest co-directed feature, 7 Walks with Mark Brown (2024), a lyrical portrait of the eponymous paleobotanist which won the top prize in the festival’s International Competition, capping a successful run that saw the French duo make a rare stateside appearance the previous fall at the New York Film Festival.

When we met, they were preparing to return to New York for the film’s U.S. theatrical opening, despite Creton’s aversion to traveling. “He’d rather be with his plants,” Barré cheekily remarked as we walked through Tui’s cobblestone streets, referring to the fact that Creton is not just a filmmaker but also a farmer. This is something that seemingly every article about Creton must point out, and not without reason, as most of his work deals in some way with nature, wildlife, or horticulture itself. In an interview with Nicholas Elliott conducted during NYFF and published by BOMB, Creton admitted that “there is something a little paradoxical, even contradictory, about traveling all this way to show a film about these walks. It’s a compromise.” Indeed, one gets the feeling while watching Creton’s films, which are largely shot around the Pays de Caux region of Normandy where he lives, that he would be perfectly content never leaving the French countryside. For him, it’s a matter of ethics as much as energy or enthusiasm.

Barré works primarily as a sculptor, having only come to filmmaking in his early fifties. By the time of his first short, Les Chambres (1998), a tranquil study in light and space shot between his sculptor’s studio in Saint-Firmin-des-Bois and a cabin in the Charousse mountains, Barré had spent more than a decade studying and working in North America—first with celebrated architect Louis Kahn in Philadelphia and then throughout the 1970s with the Barton Myers architectural firm in Edmonton and Toronto. Upon returning to Paris, Barré pivoted full-time to sculpture, developing a flair for large-scale objects rendered in cast iron, bronze, and aluminum—a monumental style belying the modesty of his future experiments with the moving image. Like Les Chambres, Barre’s five subsequent shorts flit between provincial France and various far-flung locales, something that definitively separates his solo work from Creton’s, which rarely ventures beyond Normandy. (Not for nothing is the French DVD set of Barre’s films titled Voyager – Filmer.) The following year’s Fragments of Landscape, for example, finds Barré filming in two different locations in Spain’s autonomous Castile and León province, where he sketches a largely observational portrait of the region’s rugged terrain, while 2001’s Amer uses the story of a boy the artist met in his youth on a trip to India as a framework to reflect on the region’s tumultuous history in the years since, from the 1984 Bhopal gas tragedy to a 2001 incident in which the Taliban destroyed a pair of Buddhist statues in Afghanistan. (Barré has described the theme of the latter film as “sculpture as resistance.”)

“Vincent likes traveling, I don’t,” Creton wrote in a 2019 program note for the Viennale about the first film he made with Barré, 2005’s Detour, followed by Jovan from Foula. “Nevertheless,” he continued, “we will try something: to film together to see if our experiences of traveling and of sedentariness align.” Thus far, the arrangement has proven fruitful: two decades of coauthored work has followed, with each film an ever more revealing microcosm of their respective passions and peccadillos. Far stranger and more playful than their backgrounds might suggest, Creton and Barré’s films subvert both narrative and nonfiction traditions, as well as notions of autobiography. Just as the duo often appear in their documentaries, they frequently perform in their fiction films. In 2017’s Creton-directed Va, Toto!, the filmmakers play a pair of neighbors-turned-lovers in Normandy, where an old woman’s pet boar disrupts the community as it grows larger and more ornery. Meanwhile, the aforementioned erotic fantasy A Prince (also credited to Creton) features them as two-thirds of an intergenerational gardening throuple. In both films, direct dialogue is minimized in favor of voiceover narration by famous actors, including Mathieu Amalric, Françoise Lebrun, and Jean-François Stévenin, creating just enough distance between the performers and the characters to upend any strict correlations between the stories and the couple’s relationship, though the biographical resonances are hard to miss.

The further one delves into Creton and Barré’s catalogue, the more the films begin to feel like pieces of an indivisible whole, one that encompasses the entirety of their personal and professional lives. (“My life is made for the films,” Creton says later in the same BOMB interview. “At the outset there might have been a life choice before an artistic choice, but very quickly everything was intimately connected.”) To fully appreciate the formal and interpersonal particulars of 7 Walks with Mark Brown, one would do well to consult 2006’s The Arc of the Iris, Souvenirs of a Garden, in which Creton and Barré examine plant life in one of the highest-altitude places on the planet: the Spiti Valley in the Himalayas. Here, the cinematic herbarium conceit of the new feature is seen in chrysalis, with radiant images of the region’s flora—much of it the same, they discovered, as what grows in their gardens in France—paired with onscreen text denoting each species. It was at an early screening of Iris where Mark Brown suggested that the artists make a film with a similar concept in Normandy, an idea they returned to almost two decades later with the scientist himself as de facto tour guide. Structured in two parts, 7 Walks follows Brown across Pays des Caux as he searches for plants for an ancient garden. The first half, shot digitally, documents these journeys, while the second half, narrated by Brown, presents a visual record of his findings in 16mm. Slippery but never showy, the film’s shape reveals itself with the same sort of quiet ingenuity as Creton and Barré’s more fantastical fictions.

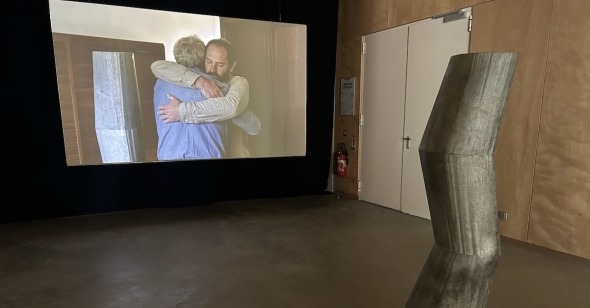

A couple of months ago, during a stay over in Paris between the Locarno and Venice film festivals, I spent a day about 120 kilometers south of the French capital at Barré’s farm, where the barn-turned-studio seen in his early shorts had been picked through for sculptures for a career-spanning exhibition at Les Tanneries–Centre d’art contemporain in the nearby hamlet of Amilly. Before heading to the museum, we stopped at a farmer’s market and then at a patisserie, where Barré loaded up his car with bags of leftover bread for the geese that reside on his land, followed by a homemade lunch of lamb, cheese, salad, bread, wine, and potatoes—all locally sourced, with the exception of the latter, which, Barré noted, came from Creton’s garden. Arriving at the multilevel exhibition—its title, “A Family of Rooms,” perfectly evocative of the floor plan, in which an atrium filled with the artist’s sculptures (plus a single-channel video projection of two men embracing, taken from 2019’s A Beautiful Summer) sits beneath of pair of galleries featuring works by a selection of Barré’s influences and contemporaries, as well as his own sketchbooks and drawings—I was struck at once by the enormity of his vision and the intimacy of his craft. His sculptures, oftentimes arranged in pairs and positioned on their side or at oblique angles, resemble fallen objects as readily as they do medieval-ish contraptions; variously beveled, jagged, naturally textured or treated, they set assumptions regarding the found and the finessed in stark relief. Barré is something of a local celebrity, and his work can be seen throughout Amilly, whether in front of municipal buildings or along the turnpike; with the mayor who commissioned these pieces recently retiring and the sociopolitical climate in the area shifting toward the far right, Barré considers the exhibition a kind of spiritual capstone to a decade’s long relationship with the community.

Sitting in the courtyard outside the exhibition, Barré—still a little tickled that a cinephile from Los Angeles a few decades his junior had traveled thousands of miles to discuss his practice in person—graciously answered my questions about his winding career path, his films with Creton, and the relationship between his work in cinema and sculpture.

Reverse Shot: When did you first meet Pierre?

Vincent Barré: The first step was through Sophie Roger, the assistant cinematographer on 7 Walks with Mark Brown. She was a student when I was coordinator of the master’s program at École des Beaux-Arts. We had a good relationship, but we didn’t know each other so much yet. After the term had finished, she asked me to come to Normandy to show me some works at a studio she was trying to establish. When I arrived, she said, “We’ll have lunch at a friend’s place. He lives in a chicken house under a cliff.” The friend was Pierre.

He received us that afternoon with potatoes from his land—the same potatoes you and I just ate—and cabbage from the cliff. So we had cabbage, potatoes, and snails from the sea. He had no electricity and no running water. He lived there for maybe ten years. This was 1994. And ten years later, I’m back there—I sold a sculpture in a nearby village to some collectors. I came to install it, and I think to myself, “Oh, this is close to where my student Sophie had taken me. What is the name of that guy I met? Oh yes, Pierre. But Pierre what?” I can’t remember. Then I see a poster that says something about a Pierre Creton film screening. So here I find his name in this small town, and I call up Sophie and I ask, “What happened with this guy?” A few months later, she asks me to visit her studio, and this is when I meet Pierre again. When I get there, he’s filming—it was an open works exhibit, so there was work by Sophie and Pierre and a figurative sculptor friend of theirs. This is actually the scene you see at the end of Secteur 545 (2005), which is a film Pierre made while working at various farms, milking cows and taking samples of each cow. At the time he was working at something like 20 farms every month, mornings and evenings. After a while, after figuring out who the people were and how they worked, he decided to start shooting, and he made this film, which is outstanding. It's his first feature. It's a key film for most of what came afterwards.

So this day when I came to visit the studio, he’s shooting the end of his film. And there I am with a stupid red and black shirt, cowboy style, chatting and showing off. But I didn't know what he was doing. I said, "What the hell are you doing?” And he said, “Oh, just making images” He didn’t tell me he was shooting a film. A little while later we met again, and that’s when I showed him my films, and he showed me his films. But before then I didn’t even know he made films.

RS: What did you think he did?

VB: Just rural labor. And drawing. This was all I knew. He showed me this bizarre drawing with sperm splashed between two sheets of paper. He explained that he had spent a whole residency in a hotel room, not going out, just jerking off. [Laughs] It was so bizarre to me. But this is how we met, and you can imagine the end of the story.

If we hadn’t decided to make films, I am not sure what sort of friends we could have been, because we can’t just stare at each other and melt in love forever. Films allowed us to do things—even just walk together. Because the first films are walking films, like Detour, which was shot in Scotland, then The Arc of the Iris, which was made in the Himalayas. Even Petit Traité de la marche en plaine (2014), which is based on writings by the Swiss poet Gustave Roud—it’s about a walk through the plains. This is how we started.

RS: How did you come to cinema? What kind of movies were you watching before making your first films?

VB: At the beginning, I wouldn’t have called or considered my films cinema. I didn’t make a link between what I saw as movies and what I do. I also have no memory, so I forget the names of films, actors, filmmakers—everything. When you talk to Pierre, he’s a dictionary—it’s incredible, for cinema as well as literature. He can tell you the music of that film and what other films this filmmaker has done. I feel like an asshole when I listen to him speak to other people about cinema. But it’s not that I had no culture at all. I had seen a lot of Japanese films on my own because I would escape from high school and go to the Left Bank movie houses. I saw Japanese films, Russian films. I saw Tarkovsky films very early on.

RS: What Japanese films, like Kurosawa or Ozu?

VB: Kurosawa, yes. I discovered Ozu much later. I saw Russian films like Alexander Nevsky (1938)—these sort of films. But always old films. Stuff like the nouvelle vague—I didn't even know what that was about. Godard would have been too fussy for me. I knew literature because people would talk to me about it and recommend things for me to read. I learned about ancient music the same way. But I was a self-made man with cinema. When I look back on the way I made my second short, Fragments of a Landscape, I put together short sequences, one after the other, with no apparent link, and in a rather naive way. I thought, “Oh, each shot has to be five seconds long, bum bum bum…” Occasionally something is moving in the image, so the camera follows what’s going on, and other times it’s still, and a figure passes through the frame. I call them my baby films.

I had some intuition. I knew a little about photography, because of people like Daniel Boudinet, whose photos you see in the exhibition. Daniel was a great friend; he died very early of AIDS. He made photos in my studio, and he would speak about landscape and framing. So I had a real sensitivity for framing and for sound—hearing sounds. But it took me a while to incorporate words. My first film is totally silent. I didn’t want to romanticize my story or express my feelings. I found that indecent. What I did instead is write in my sketchbooks. So for Detour, our first film together, Pierre picked sentences out of my sketchbook and had me read them while the camera moves in fixed 360-degree pans of the landscape—ten shots corresponding to the ten years we were separated after first meeting. That was his idea.

RS: What do you think it is about your process or personality that made Pierre want to work with you?

VB: What he often says is, “I make films with people I love.” So first came the relationship. And then he said to me, “You are a traveler. You know how to travel. I cannot. So the condition is that we make a film. And then you make all the decisions. I trust you.” Which he really did, even though these were difficult trips. But he’s physical; he’s strong; he has a good mind; he’s not fussy with anything; food is never a problem. The only thing is he gets a fever when something is too much for him. His body reacts. For example, we arrived in India [to shoot The Arc of the Iris] after three days of travel—by plane; then a bus through a small town at the foot of the Himalayas; then another bus for one full day through a pass at high altitude. It was very dangerous, and we could hardly find food. He had a 40-degree fever for three days. Even as late as last spring when we had to go to Ghent, in Belgium, which is one hour by train from Paris, he got sick the day before. Somehow he didn't get sick when we went to New York this summer.

RS: How do you come to your specific duties on each film? Sometimes you’re credited as a co-writer; other times as co-director; for the new film you even did sound.

VB: Yes, it’s different duties each time. For 7 Walks, I couldn’t handle any of the cameras. I felt useless. So, I said, okay, let me take care of the sound. And I’ll make sketches. I followed what was going on, and listened to Mark when I could, but I was often recording ambient sound. It depends on the tools. If I have a small camera, I can shoot myself. Then we have Pierre’s rushes and my rushes, and we can put them together. Early on, for the films in the Himalayas and Scotland, we shared tasks like this. Eventually he changed cameras, and now I’m often either performing or speaking.

RS: Has anything else changed in your process between those early films and 7 Walks?

VB: We had a very intimate way of working together for the first ten years. Through Pierre, I understood that cinema is a real collective action. It’s not abnormal to have a three, six, eight people around. I’m solitary, like he is, but he knows the economies of cinema. So, for him, it’s natural, and he enjoys it. Like I said, he makes films with people he loves. For 7 Walks, there’s Sophie, whom he has known since adolescence; Pierre Sudre, whom he has known 35 years; Antoine Pirotte, the cinematographer, is probably the most recent one.

RS: It was just you two for the early films?

VB: Yeah, just the two of us. And now—it’s not big compared to normal productions, but for me, it’s a lot. What’s new, too, is that in the last eight years, Pierre has made fiction features—fictions from life, but fictions. And he’s asked me to participate on the scripts, and eventually to perform as well. So, in Va, Toto!, I played the Vincent character. I write easily when it’s my story. I couldn’t make a totally invented fiction. I have no imagination for that. I like to find a path with my own stories.

For Va, Toto!, I told Pierre that as a child, around the age of 15 or 16, I would be punished on weekends because I was lousy at school. So what would I do? I would go cruising outdoors on the riverbank, where there were these little shops where they would sell animals, including tiny monkeys. I fell in love with these monkeys, and I started fancying that I would make a jungle in my bedroom for these monkeys, and they would be happier in my room than in life. This was an early example of the erotic mixing with fantasy. At this time, I was being beaten badly by my father, while also discovering my sexuality—and Pierre knew this, so he picked all these elements in the script to build up. There are elements of my story in that film and A Beautiful Summer, and even more in A Prince, where the teacher character I play takes a young guy as a lover for a night. I write heartedly because it's my life.

RS: You mentioned to me that you believe your sketches are a key to your work, or a way into looking at your cinema. Can you expand a bit on the correspondence between the sketches and what you film?

VB: Sketching is a way of sitting and memorizing where I am, what I see, what people I am with, places. But the correspondence doesn’t always come at the same moment. Last year, around this same time, I came back from the Himalayas, but because of an issue with a bone in my back, I only did one or two drawings in four weeks. That was a sign. It was a message. The idea that I just leave home and then here I am in the middle of nowhere, sketching, thinking, having wonderful thoughts—this is romantic. It’s how I spent my teenage years, and then my young professional years, and so on. But now I have changed. To find this state of peace or innocence, it has to come from a decision. That’s how it is when I do things with Pierre. It begins with a decision, and then we let it flow—it’s very fluid. There’s no effort, no chaotic moments. So I have to find that by myself again.

RS: At this point in your career, do you consider yourself one thing over another: a filmmaker or a sculptor, a visual artist or just an artist?

VB: I feel split. Because these two practices, filmmaking and sculpting, have little to do with one another, unless I conceive a film around my activity as a sculptor, like Mètis (2007), or my first short. For the first film, I didn’t know Pierre, but for Mètis, he accompanied me and we did the editing together—we basically made it together. But it was clear going in that I wanted to make a film of my own about sculpture, and I wanted to shoot between my studio and a Mediterranean monastery in Greece. So I went alone to Greece and I filmed, and I chose the texts, and I didn't add too much. When doing these films I’m another person, in a way. I am the same Vincent, but it’s different tools. For example, the sculptures for this exhibition—everything was installed in the beginning of May. But before that I was completely paralyzed in my studio. I couldn't do a thing until three days before, when I had this assistant stay with me and we decided on what to include. Then I was more confident to continue. Like a lot of artists, you fear the end of your inspiration. The way Pierre reacts to this is that as soon as something is finished, he starts something else. So what happens is he has five things going at a time with different friends. And this is the way I used to be; when I was an architect, I had several projects going at the same time. Now it’s different. Maybe I have to come to the stage of my life where I’ve realized that I’m not David Lynch, who kept rushing like a bull until the last breath. For me, it’s now a moment when I have to maybe consider being still, even if people often tell me that I have to make another film.

RS: Why did you stop making your own films?

VB: I’m shy with the camera. And the camera that I fell in love with, my first camera, was stolen from my farm. Now the technology has changed, and I can’t find the equivalent. I need something easy, small, that I can carry with me. Everyone tells me, “You can shoot with your telephone.” I find that horrible. But it will happen. I will go on. I have to. I’m 77, but I am young. I have to go forward. I will make a film.

Photos: Jordan Cronk