Live Wire

Sarah Fensom and Chris Shields on The Art of Tom Cruise

The screening series Tom Cruise, Above and Beyond runs June 20–August 17, 2025 at Museum of the Moving Image.

Near the beginning of Top Gun: Maverick (2022), Pete “Maverick” Mitchell (Tom Cruise), a captain in the United States Navy and a decorated test pilot, is told that the Navy is planning on scrapping the hypersonic aircraft program he’s been diligently working on. The logic is that drones should replace military aircrafts operated by pilots, due to the myriad needs and potential vulnerabilities of humans. But, as we already know from 1986’s Top Gun, it’s Maverick’s nature to defy both protocols and limitations, so he takes the jet into the air and hits its heretofore unachieved target speed of Mach 10, proving what humans can do after all. (Though, it should be noted, he does destroy the prototype when he can’t resist pushing it even further.)

That Maverick is played by Cruise somehow provides more information about him than any preceding film ever could. Tom Cruise characters are known for having chips on their shoulders, excelling at their chosen fields, and achieving things that nobody else can. His movies, like his most recent outing, Mission: Impossible—The Final Reckoning, even include pieces of dialogue that explicitly acknowledge that his character is the “only one” who can achieve a specific goal (here, vanquish a dangerous, rogue AI, presumably both Ethan Hunt’s and Cruise’s real-life inhuman nemesis). In the case of Top Gun: Maverick, Cruise’s goal, as the movie’s PR made clear, was just as challenging as his character’s: he was to bring audiences back to the movie theater in the wake of COVID-19 and consumers’ near-complete transition to streaming services. While promoting the film, Cruise also emphasized that the action was done using practical effects and stunts, providing the audience with a sense of immersion and realism that CGI can’t achieve—touting man over machine, just like Maverick.

Cruise’s quest in Top Gun: Maverick emphasizes the reflexive nature of the actor’s Hollywood career. He is in many ways the meta-movie star, with the characters in his filmography and the trajectory of his career charting the same path. Cruise’s roles have evolved from the brash young colt who is preternaturally talented but needs to be tamed (The Color of Money, Top Gun, Cocktail) to a series of radical roles that subverted his own persona (Born on the Fourth of July, Eyes Wide Shut, Magnolia) to the singularly capable middle-aged superman (Jack Reacher, the later Mission: Impossible films). As an actor and a star, Cruise has similarly evolved from the manic, sometimes histrionic performer (expertly lampooned by Ben Stiller in a classic sketch during the 2000 MTV Movie Awards) to a much more staid presence—now in charge of saving movies and protecting the 20th-century American movie theater experience.

But the current myth and meme-ification of Tom Cruise leaves out many of the specifics of the actor’s versatile and daring career. Following a handful of supporting and ensemble roles in films such as Harold Becker’s Taps (1981), the surprisingly heartfelt teen sex comedy Losin’ It (1982), and Coppola’s young-star-studded adaptation of S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders (1983), Cruise would achieve true lead status with Risky Business (1983). In Losin’ It and Risky Business particularly, the gorgeous young actor imbued his teen characters with a level of vulnerability that helped give the horny proceedings an unexpected depth. Cruise brings both gentle, boyish uncertainty and exuberant teen physicality to his portrayal of Joel in Risky Business. These two dimensions—the fragile and the performatively physical—became hallmarks of Cruise’s best performances, the two coalescing to create both a hardness and an open accessibility on screen.

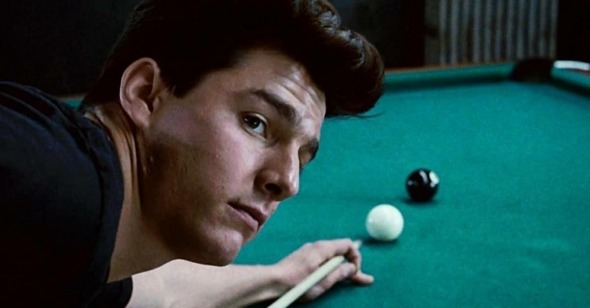

In Scorsese's The Color of Money (1986), Cruise plays opposite Paul Newman, who reprises his role of “Fast Eddie” Felson from 1961’s The Hustler. Newman’s Eddie, with his smooth talk, camel coat, and Cadillac, prides himself on always knowing the score. Cruise’s Vincent, by contrast, is a hyper kid barely out of high school, whose understanding of the world is shaped solely by the way people react to his talent. As Vincent, Cruise is at his most tri-state (the actor went to high school in Glen Ridge, NJ), with big, blow-dried hair, an Italian American–coded sense of style, and a sort of facile machismo. As in his previous films, The Color of Money is an outlet for Cruise’s explosive physicality, not only as he shoots one winning game of pool after another, but also as he showboats after his victories, whipping the cue around like Bruce Lee wielding nunchucks. In essence, The Color of Money resembles a martial arts movie in its old master and young apprentice conceit, with Cruise performing his physical prowess, and Newman doing more subtle, cerebral, and languid work. Like Scorsese acknowledges, much of a film's success lies in the casting, and the pairing of Cruise and Newman creates an implicit dynamic tension between stars of different eras at very different points in their careers. It’s a potent meta-story of the old and the new, and everything that comes along with being either. The film feels like a turning point for Cruise, acting alongside one of Hollywood’s greatest stars rather than his young peers, and perhaps because of this (and his director), the actor delivers some of his finest character work. In The Color of Money, he’s not Tom Cruise, but rather Tom Cruise channeling his talents through the character of Vincent, an important distinction.

Though Cruise provides a necessary and transfixing foil, The Color of Money is Newman’s movie, for which he won the Oscar. The opposite is true in Barry Levinson’s Best Picture–winning Rain Man (1988), which positions Cruise as protagonist Charlie Babbitt, with Dustin Hoffman as his foil, playing his autistic brother, Raymond Babbitt, whom Charlie only learns about after his estranged father’s death. Rain Man finds Cruise at his most rigorous, channeling all his gifts into a frustrated and deeply wounded character, who’s grasping desperately at whatever seems like control. When Charlie, a slick but failing foreign car importer, meets Raymond in a high-end care facility, his overwhelming feeling is irritation, and the frustration that Charlie feels early in his relationship with Raymond offers Cruise a new and interesting playground for his naturalistic aggressiveness. He’s often having emotional outbursts yet stifling his true feelings at the same time—lightning both in and out of the bottle. Throughout his career, Cruise utilizes a form of delivery, akin to the classic acting exercise, in which he says a line at a normal register, then repeats it, raising his voice and throwing his body into it. In Rain Man, this technique is at its most meaningful, as Charlie is trying to communicate with someone he fears doesn’t understand him. Notably, later in the film, after Charlie believes he and his brother have emotionally reached each other, he grows more sensitive and subdued, with his desperation now coming from his desire to prove his love, not to get answers about a situation and relationship he finds confusing.

Throughout the film, Levinson tends to shoot Cruise more in the mid-shot than close-up, which captures the subtlety of the actor’s gestures. Charlie wears flashy suits and jewelry, and Cruise lightly flicks out his wrist as if his expensive gold pinky ring is too heavy for his hand. The actor has a habit of looking away from his fellow performers in a scene, then clenching his jaw and slightly defocusing his eyes as they brim with unshed tears; he employs this technique a number of times in Rain Man. But seen from the greater distance Levinson maintains it suggests that the character is holding his feelings back, rather than using them to punctuate a cinematic moment that needs an injection of emotional depth in order to seem important. (This is something Cruise is called upon to do repeatedly in the later Mission: Impossible films.)

Hoffman took home the Oscar for Rain Man but there is no Raymond without Cruise’s Charlie. He is both the audience’s surrogate in the face of the challenges Raymond presents and a deeply nuanced character on a delicate human journey of healing. Rain Man may be Cruise’s most perfectly balanced performance alongside one of his best partners. As in The Color of Money, the casting makes the film. Hoffman’s immovability and unpredictability stymie Cruise in a way that creates electricity. And what this particular dynamism allows for is unique for a Cruise character. Unlike in Top Gun or Days of Thunder, the actor does not succeed in his chosen mission, he does not defy the odds to prove his great talent. Instead, he learns. It’s beautiful to watch. Cruise’s Charlie gains something, a new emotional register and a new relationship and understanding. Free of the trappings of other Cruise vehicles where some great, external odds must be overcome, the film creates a space for purely dramatic, character work—the stakes are lowered but the impact is far bigger.

The subtlety and restraint of his performance in Rain Man were purposely jettisoned for Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July (1989). The film features perhaps Cruise’s most ambitious performance, as Ron Kovic, a wounded Vietnam veteran who eventually becomes a notable antiwar activist and veterans’ rights advocate. All the bombast Cruise can muster is brilliantly harnessed by Stone, or more properly thwarted for a purpose. Cruise is in a wheelchair for a large part of the film, and this impediment to his usual physicality gives the film a palpable tension, allowing the actor to embody seething, impotent violence as sadness. Stone’s casting of Cruise, the military hero of Top Gun, gives the film a postmodern radicality as an antiwar statement. One of the film’s most painful and subversive scenes is an inversion of the typical, iconic Cruise scene where the actor showboats and struts. In the veterans’ hospital, Kovic is told he’ll never walk again, something he can’t accept. We watch as the paralyzed vet hoists himself around the hospital on crutches dragging his legs behind him. Ron shouts in glee, affirming that he is healing and on his way to walking once again, yet, there’s a sense of foreboding. His movements are out-of-control, his energy manic, and soon he falls, hurting himself more severely. His accident is the definitive answer that he’s been dreading—he won’t be on his feet again.

After Born on the Fourth of July, Cruise’s next notable work came in Rob Reiner’s A Few Good Men (1992). Playing opposite Jack Nicholson, the actor finds another meaningful foil. In the film Cruise plays a hot shot military lawyer who is tasked with defending two young marines who have killed a fellow soldier. Nicholson is the arrogant, self-important embodiment of the military status quo, the unquestionable last line of defense for America. His belief is that when it comes to protecting the country (but really his own status as above that of the civilians he’s allegedly safeguarding) anything goes. Cruise on the other hand is a young preppie who doesn’t think much of military protocol or tradition. His hope is to move on to big money and success in the private sector. The film creates a space for two major face-to-face conflicts between the characters and actors, the most famous being Cruise’s relentless interrogation of Nicholson on the stand, which results in an explosive confession. It’s like an exhilarating car race between two expert drivers jockeying for position at high speed. But the actors offer something perhaps more unexpected and unique in their first encounter. Cruise’s character flies to Cuba to get a statement from Nicholson, a fairly perfunctory part of the legal process, but once there the old military man can’t help but dress down the young lawyer and show his contempt for him. It’s Cruise once again playing against his usual bombastic type, suffering Nicholson’s arrogance and insults without much of a reaction. These two scenes create a strong character dynamic which pays off in the film’s powerful finale.

Neil Jordan’s Interview with a Vampire (1994) turned the tables on Cruise; in the film he acts alongside Brad Pitt, a talented young star and sex symbol who was ostensibly Tom Cruise 2.0. Cruise plays the aristocratic vampire Lestat with a foppish flair. He luxuriates in his surroundings, melting into chairs and couches, decadently guzzling his victims’ blood. The performance represents a big swing for Cruise. This recontextualization of the actor as the expert indoctrinating the ingenue is meaningful but less so than his persona-subverting work with Stone and Stanley Kubrick, and while the pairing of Pitt and Cruise is conceptually intriguing, it doesn’t generate the spark he created with former co-stars. With Mission: Impossible (1996) Cruise synthesized his movie stardom and abilities. Brian De Palma’s film is both a big-budget action spectacle and a tense, well-acted thriller. Cruise is giving his all, never forsaking character and psychological realism. The reality of Mission: Impossible, its expert direction and Cruise’s intense, layered performance, are maybe what has driven the massive franchise for so long—in the beginning there was a film of real substance that has been able to endure a steady dilution in its sequels.

Cruise would continue his persona subverting work in Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (1999). The film, similar to Born on the Fourth of July, makes him a voyeur rather than the man of ecstatic action. The legendary director famously made Cruise do take after take (up to 70 by some accounts) perhaps to sap the actor’s energy, in essence making a virile performer impotent in a film about sexual fantasy and jealousy. It’s a clever and pointed use of the actor, less politically meaningful than Stone’s but very much in the same line of attack. Cruise’s Ron Kovic is literally impotent as well, in fact it’s one of the key parts of his character but not all. Kubrick’s film takes this idea and runs with it for perhaps more Freudian and class purposes, subverting both the actor and the idea of Cruise as sex symbol and energetic performer. More than a refutation of the American myth (the “big fucking erect penis, Mom” in Stone’s film) it is a refutation of a mythic masculinity.

Cruise would again be used to riff on his own energetic, sex symbol persona in Paul Thomas Anderson’s magical realist Magnolia (1999). In the film Cruise plays a back-flipping, proto-manosphere motivational speaker and dating coach. His showmanship and anger are exhilarating, but while this is an often hilarious performance up to a point, Cruise’s dramatic work with Phillip Seymour Hoffman and Jason Robards win the day. He plays two sides of the coin, the preposterous alpha and all the hurt vulnerability beneath. It’s a somewhat simple characterization but a powerful one nonetheless that puts a fine point on what was popularly understood to be “Tom Cruise.”

While many great films followed, this is arguably the end of Cruise’s serious dramatic work. He would bring his impressive abilities to Vanilla Sky (2001) and enliven his two collaborations with Steven Spielberg in much the same way he energized Mission: Impossible, and he delivered an effective villain turn in Michael Mann’s Collateral (2004), against another great foil, Jamie Foxx. As the 2000s went on, Cruise would slowly become what we know him as today: the biggest star in the biggest movies. The return to the earlier success of Top Gun is notable however, mainly because it is not a subversion of his persona but an affirmation of the Tom Cruise myth. This myth would have less meaning, however, without the great, subversive performances that came before it.