The View from Here:

Reconsidering the Video Essay at MoMI

By Dan Schindel

Expanded Screens: The Video Essay shows January 3–5, 2024, at Museum of the Moving Image.

The rise of affordable filmmaking tools, the internet, smartphones, and social media platforms have led to many words written in the 21st century about the broadening power to create and distribute cinema. In parallel, there has been a related but less-discussed rise in the essay film. Once specialized territory for the likes of Chris Marker and Thom Anderson, the video essay—or at least, some discursive form related to it—has grown to become a primary communicative mode. A representative sampling of noteworthy videos from the past two decades comprise MoMI’s series Expanded Screens, a survey of the essay film’s recent evolution. Programmers Will DiGravio, John Gibbs, Evelyn Kreutzer, Kevin B. Lee, and Mara Oliva are all video essayists themselves and thus suitable guides for this realm.

Within cinephile circles, video essays broke into new prominence in the early 2010s, as video-sharing sites (particularly Vimeo, which emphasized higher visual and audio quality and more producer-friendly tools than YouTube) brought experimental and scholarly works by film professors and students to wider audiences. MUBI began sharing video essays in 2010 via its criticism site Notebook; Fandor started a dedicated section for video essays on its Keyframe blog around the same time; and [in]Transition, the first journal on the form, launched in 2014.

Coming from the world of film-focused academia, these essays are concerned primarily with some kind of analysis and/or criticism. Popular YouTube channel Every Frame a Painting, for instance, appealed to a broad audience by explaining filmmaking techniques through salient examples—using the work of Spielberg to illustrate long takes, Satoshi Kon for editing, etc. In this period, the cinephile video essay was directly related to other forms of internet sharing that almost fetishized isolated imagery and moments from film, like Tumblr GIF and photo sets. Another essayist, kogonada, parlayed his popularity here into collaborating with Criterion to make videos accompanying such releases as House before going on to make his own feature films.

The first program of Expanded Screens, Where Does Film Live?,presents essays that explore film through film. In Void (2023), Kevin L. Ferguson examines the cyclorama, a featureless solid-color background that’s become a staple of music videos and advertising. The various works on display in Ferguson’s film all seem to take place within the same setting, emphasizing his analysis of their use of negative space. Jessica McGoff’s My Mulholland (2020, pictured above) stands in for the rich vein of personal film criticism that’s emerged in this genre, interspersing her written reminiscence about her burgeoning cinephilia as a teenager with scenes from Mulholland Drive, as she describes the impact the iconic diner parking lot scare had on her.

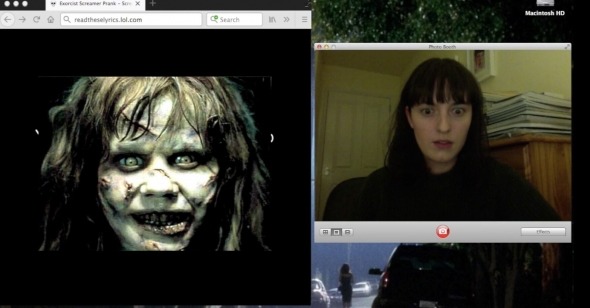

My Mulholland is also partially a desktop film—a format in which unpacking cinema in cinema finds perhaps its purest practice. Such works simulate the medium through which viewers engage with them. Maria Hofmann’s Sticky (2024) evokes the sense of ambient horror that’s now an everyday part of browsing the web. It makes literal the act of compartmentalization, showing videos of the Mediterranean migrant crisis in a window alongside more mundane ones for email and work.

Video essays can also dissect the relationship that media builds between people and familiar spaces—which MOMI’s second program refracts specifically through videos about NYC, titled Remixing New York. One of the archetypal examples of how formal playfulness can translate to online virality, LJ Frezza’s Nothing (2014) is a supercut of shots from Seinfeld, famously “about nothing,” which contain no human beings. In the absence of the actors whose scheming and collisions animate the sitcom, the essay draws out the sets that usually recede from the viewer’s attention, encouraging them to notice the subliminal details of production design that flesh out this world. It takes a lot of effort to make a long-running series about nothing. Frezza went on to work as an editor on How To with John Wilson, an epochal take on life in modern New York. The public becomes keenly private in 2010’s The Best of Everything Chapter One: Quantum of Solace, in which Steven Boone utilizes the essay as a memoir. Through his edits, scenes from films he’s been thinking about and scenes from New York are part of the same stream of consciousness, filtered through reminisces on his life and moviegoing habits in the city over the previous decade.

Some essayists interrogate modern media’s relationship to older mediums, as seen in the fourth program, Out of the Past. Lee’s visit to the site that was once home to a movie theater that was a staple of his childhood (closed off to him due to COVID-19) becomes the basis of Explosive Paradox (2020). In it, he reflects on seeing Platoon and how its portrayal of violence and handling of race (along with his father’s reaction to it) has lingered to this day, the mundane suburban milieu grating against the darkness of his spoken recollection. Cydnii Wilde Harris surveys the relationship between cotton-based agriculture, slavery, racism, capitalism, and cinema in Cotton–The Fabric of Genocide (2018), which collates newsreels, educational films, and ads. In just four minutes, Harris sharpens this series of images toward a pointed demonstration of how mass media can sanitize bloody history like a bleached cloth, closing with a sunny modern ad from Cotton Incorporated’s long-running “The Fabric of Our Lives” campaign.

As the name suggests, the third program, The New Avant-Garde, presents essays that break the aesthetic or discursive mold. One of the most consistently intriguing voices in this space is Maryam Tafakory, whose 2022 piece Nazarbazi is a terrific representative for her oeuvre. Many of Tafakory’s essays deal with Iranian censorship of the arts, with this one addressing the sanction on physical contact between men and women. Rather than merely explain this history to the viewer, she creates a tone poem of repressed lust and romantic longing out of charged romantic scenes from Iranian films, which had to convey their characters’ emotions despite the prohibitions at play. The gaze becomes similarly perilous in Christopher Harris’s Reckless Eyeballing (2004), an optically printed rapid-fire montage of Black and white faces intercut with newsprint alluding to the Jim Crow law the title refers to, which forbade Black men from looking at white women.

Within the modern maelstrom of information, those who make video essays as a dedicated practice—whether they’re academics, independent filmmakers, or Patreon-supported YouTubers—can help us thresh the noise for useful signals. All the selections in these programs demonstrate the ways video essays can condense multilayered topics without losing any of their complexity. Films like Sticky, Nothing, or Cotton take apparently simple premises but reward careful attention and invite continued revisiting. Removed from their regular home on the internet and projected in a theater, they can command audience attention anew, and reveal further layers.