A Little Chaos

Nick Pinkerton on Going South

Going South plays Saturday, January 19 as part of Museum of the Moving Image’s First Look 2019.

Let us presume for the moment that the end of the world really is nigh. Let us suppose that it isn’t going to be a peaceful chiliastic bail-out, but an end self-imposed by cupidity and negligence and sybaritic stupidity, and that it will be terrible and painful, perhaps experienced by many even now living on the planet. Let us suppose that Paul Schrader, the always Cassandra-like writer-director of First Reformed (2017), is on the money when he states, as he did in a recent interview, that “the odds of our species outliving the century are not very strong,” and that the best we can hope for is that “whoever comes after us, whatever life form or silicone-based life form that is, they’re gonna have a hell of a museum.” Putting all else aside, what might the last room in that museum look like? What should art look like made with the understanding that it might be among the last art being made by human hands?

One possible answer to this question lies in the work of the Quebecois bricolage artist Dominic Gagnon. Gagnon works in the medium of the collage film—we’ll use the term for historical purposes, though celluloid has nothing to do with his practice—a medium that is perhaps particularly if not solely suited to embodying the sensation of social and cultural breakdown, of being buried underneath an avalanche of detritus. Bruce Conner, in the 1950s best known as a scavenger-sculptor and one of the innovators of the modern collage film along with the Canadian Arthur Lipsett, produced a landmark work with his A Movie; a tissue of automotive chaos, odd exotica, softcore cheesecake, athletic novelties, collapsing bridges, aerial warfare, a burning Hindenburg, and the occasional mushroom cloud, it was finished in 1958, shortly before Conner retreated with his wife and child to Mexico in order to avoid what he was certain was an imminent nuclear holocaust. More recently, the collage film has entered a new renaissance period thanks to ready access to home video, online user-generated content distribution platforms, and nonlinear editing systems, allowing for the drubbing derangement of, say, Derrick Beckles’s TV Carnage (1996-) trash television trawls.

Gagnon has been making films for some 20 years, and for at least a decade now has been using uploaded found footage culled from YouTube as his raw material, the first of these works that I’m familiar with being 2009’s RIP in Pieces America, a litany of webcam testimonials united in their having been “flagged for content” and by their air of political disillusion, paranoia regarding Deep State autocracy, and apocalyptic presentiments, with primarily male speakers advising the stockpiling of food and arms in the face of the coming crackdown. Since then he has made works focused on North American women in survivalist mode (2011’s Pieces and Love All to Hell), a parade of online odds-and-ends set to the pronouncements of Guy Debord (2012’s Society’s Space), and teenagers anticipating Armageddon (2014’s Hoax_Canular), an ongoing encyclopedia of imagery of a civilization suspended between Singularity and Spectacle. Presently he is at work on a tetralogy, of which Going South is the second part, following his 2016 of the North—the idea, presumably, is to round the compass. The previous film was comprised largely of footage submitted by users in the Arctic Circle, the majority of them Inuit—the title recalls Robert Flaherty’s pioneering work of documentary ethnography Nanook of the North (1922), but operating from the remove of broadband, Gagnon effectively eliminated the physical presence of the interloping observer-outsider.

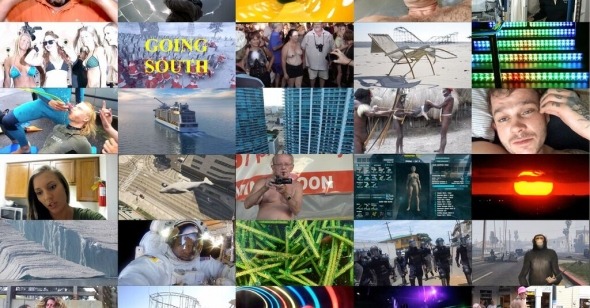

Going South is not so geographically specific as its predecessor, though its recurring scenes of palm trees engulfed in flames do lend a somewhat more tropical air to this travelogue that takes us from Miami Beach to Mozambique, from Hurricane Sandy to Hurricane Wilma. Rather than any single latitude, the imagery here locates us generally in the vague terrain of vacation, retreat, getaway—there is merriment on waterslides, bros in wetsuits barfing up the contents of beer bongs, and a nude woman well into middle age being airbrush body-painted before strolling the precincts of a Fantasy Fest street fair in Key West. Very often, though, there is trouble in paradise, with things found going terribly awry on account of either environmental catastrophe, human incompetence, or a combination of the two. A cruise ship swimming pool is seen sloshing about in choppy waters; parasailers are blown off-course by an incoming storm; airplanes are disturbed by incoherent and insurgent passengers or witnessed in the process of crash landing protocol. Between these vignettes, there gradually coheres an ensemble cast of characters made up of various YouTube vloggers who reappear throughout the film, some of them connected to the travel and leisure industry—a Charlotte, North Carolina-based flight attendant seen guiding her some 47K followers through the contents of her grocery bag, or Andy Mallon, a splenetic middle-aged American expat in Bangkok who dispenses advice as to how to kibbitz with the local bar girls without losing your heart and wallet. (He also, it transpires, hawks his own line of Teespring products.)

While pointing toward equatorial climes, the title also holds a double meaning—Going South as in to deteriorate, to go downhill, to decline and fall. In the space of six chapters introduced by on-screen titles like “dear haters” and “Flat earth theory”—the latter a reference to a clip posted by YouTuber The Real Merkabah, describing with credulity the possibility that the spherical globe is an illuminati-administered sham—we traverse the planet and even travel out into the stars, but find precious little to inspire high hopes for the future of humankind. Self-improvement and self-realization is much spoken of by several of our vloggers, but jumping between confessional entries, what we actually see is a Sisyphean sort of struggle, a process of incremental gains and inevitable backslides. One fortysomething man, self-described on his channel as your “average night owl tattooed music lovin’ car salesmen computer guy... recovering alcoholic, battling anxiety and alcoholism” is seen voicing firm resolutions in between losing his battles time and again. Chloe Arden, a Canadian transgendered teenager, is seen vacillating between euphoric highs of empowerment (“You gotta do what makes you happy because in the end you’ve only got yourself”) and troughs of long-dark-nights-of-the-soul despair, unloosing a depressive soliloquy in a Walmart parking lot and voicing the great conundrum of our times: “I just, like, want more… subscribers, to be honest. I just want a bigger audience.”

Gagnon has not merely laid clips end-on-end here; he is often found suturing different pieces together so as to make them appear to be occurring in the same space, as when the partying of the beer bong bros seems to be interrupted by the goblin-like gibbering of a woman, viewed only as a twitching hand reaching from what appears to be a bathroom door—in fact sourced from an entirely different YouTube clip labeled “Venice Beach Female Transient Freaking & Tweaking On Crack + Heroin.” He routinely lets audio from one clip spill onto the video from another, as when Arden’s monologuing about her coming out plays over Spring Break Nationals Bikini Contest footage; or a confessional from a YouTuber named RV Debs discussing the death of her husband is placed over the Key West party-time footage, creating the false impression that the woman strolling around nude is a recent widow; or when the transient gibbering carries over onto a clip titled “New Guinea Tribes meets white people first time.” (Given what we’ve seen of Western civilization up to this point, the encounter seems a mixed blessing at best.)

To grind unsuspecting men and women into the raw meat of collage is at bottom an ethically dicey proposition—I have long been troubled by a passage in one of Robert Warshow’s essays, “Re-Viewing the Russian Movies,” in which that son of a Russian Jewish immigrant muses of the masters of Soviet montage: “They would have made a handsome montage of my corpse too, and given it a meaning—their meaning and not mine.” Gagnon’s subjects aren’t corpses, of course—they’ve all willingly cast their images out into the Internet ether—but this doesn’t diminish the feeling of there being something almost anti-human in his work, which one imagines being assembled alone in a dank garret by the disheveled artist, toying with his specimens while hunched over a souped-up Macbook.

On one hand I suspect that conjuring this image has a great deal to do with reflecting my own misanthropy onto the artist; on another, I am very far from being convinced that being anti-human is an invalid artistic stance. What I can speak with certainty of, however, is the wicked ingenuity of Gagnon’s craftsmanship. In each clip he is extremely attentive in choosing his introduction and exit points, and as a result they have an almost conversational flow from one to the next. A health-and-wellness raw foods zealot finishes a tour of his spartan apartment with a shot of a book comparing the “Parallel Sayings” of Jesus, Buddha, Krishna, & Lao Tzu, concluding: “People believe in their beliefs but they don’t really believe in what they know because you only know what you know, you know?” This is followed by GoPro footage from a NASA spacewalk that looks out on the curvature of the planet, which is itself followed by a return to The Real Merkabah’s discussion of flat earth theory: “No matter high up you go, when you’re in a building you could be on the 20th, 30th, 40th floor, when you look out the window you see a straight horizon…”

The reappearance of flat earth theory in discourse is dependent on the same increasingly widespread skepticism towards any and all official or expert explanations that has allowed for the proliferation of the conspiracy-minded types who populate RIP in Pieces America, or those who insist on finding ulterior motives behind the science of global warming, even as the ice caps melt—another image that runs through Going South, inviting one to wonder just how long the many beaches we see will remain open for debauchery. Gagnon’s collage offers us a panoramic view of a human race convinced of salvation through the self, including and especially through the optimal monetization of personal branding and validation via metrics, while its shared home dies for want of collective action, mankind unable to find common cause in preserving the environment due to an increasingly epidemic mistrust in any passed down knowledge that isn’t derived from firsthand experience. In the end you’ve only got yourself! You only know what you know, you know?

Without leaving the comfort of his own browser, Gagnon has made a film cosmic in scope, including material that could be taken as his own gloss on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), shuttling as he does between outer space and prehistory, albeit a prehistory of a very contemporary sort. This comes via Virginian octogenarian gamer Shirley Curry’s recordings of her first-person play of the video game Ark: Survival Evolved, which spawns players naked and alone on the shore of a Jurassic beach, addressing an audience of her “grandkids.” (“I’ll see you in the next episode,” she signs off, “when it’s time for me to die again.”), or a clip titled “GTA Vacation Ruined” submitted by penguinz0, a 24-year-old YouTuber who’s attained online celebrity for his narration of game walkthrough footage, here a mordant chimpanzee offering a dry commentary while mowing down humans with a chain gun in a Grand Theft Auto V cityscape, an image to confound any Darwinian idea of species progress.

More than 40 years after the Sex Pistols declared “No Future,” the legacy of punk and hardcore—as an ethos if not as a codified music—remains both omnipresent and squabbled over. This can be found in the renewed attention to the corpus of Mark “K-Punk” Fisher, or in the recent titling of two movements, “Nicecore” and “Hopepunk,” pitched to conflict-averse middle-class-and-up liberals seeking to #resist renascent right-wing nationalism with snuggly goodwill, coinages seemingly oblivious to the actual provenance of punk, which was neither particularly nice nor hopeful. Gagnon, on the other hand, makes work that’s legitimately punk as fuck—bleak, scabrous, and resounding with a madman’s cackle. Watching Going South, I was reminded of some of the most nihilistic of the punk-adjacent music—of Maryland weirdoes No Trend and their howl of “Too many humans—you breed like rats, and you’re no fucking better,” or Akron, Ohio’s Devo, with whom Conner, returned from his Mexican sojourn and submerged in the Bay Area punk scene in the late ’70s, would collaborate, producing a proto-music video for their “Mongoloid.” A tribute to the modern Cro-Magnon in a Gray Flannel Suit, “Mongoloid” was an illustration of the doctrine of “De-evolution” that both shaped Devo’s work and gave the band their name. Founded on a basic rejection of narratives of human advancement, it’s a philosophy that the band member Gerald V. Casale, writing in a 2018 “Open Letter” published in Noisey, believed vindicated by recent events. Of our de-evolved present, Casale states:

“Presently, the fabric that holds a society together has shredded in the wind. Everyone has their own facts, their own private Idaho stored in their expensive cellular phones. The earbuds are in, the feedback loops are locked, and the Frappuccino’s [sic] are flowing freely. Social media provides the highway straight back to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. The restless natives react to digital shadows on the wall, reduced to fear, hate, and superstition. There are climate change deniers, and there are even more who think that the climate is being maliciously manipulated by corporate conglomerates owned by the Central Bank to achieve global control of resources and wealth.”

This last bit comes rather close to something you might hear from one of the subjects in Gagnon’s RIP in Pieces America, and looking to define what Gagnon is after in Going South, you could do much worse than Casale’s screed. And though Gagnon sometimes may seem to ridicule his subjects, on another level his work is at one with them in sharing their sense of impending doom. Summarizing his approach to the collage film, the words of one of RIP in Pieces America’s stars will do quite nicely. “It’s like a goddamn puzzle, man,” says the young man, direct-addressing the camera with an expression of fierce exasperation. “All the pieces are scattered out. Once you put them shits together, you come up with a picture, man. And I’m startin’ to come up with a fucked-up picture. For real.”