First Night:

Nosferatu

Bring your carving knives—it’s time for Reverse Shot’s fifth annual weeklong “Great Pumpkins” celebration. Usually during this festive time of the year we bemoan the lack of great contemporary horror movies while recommending seven scary selections from years past (which needn’t be exclusively horror films, per se, but which have to be appropriately Halloween-y in some way—see complete list below of prior Pumpkins). In 2009, we were able to take a break from deploring the fright-flick landscape, in the light of such terrific terrors as Drag Me to Hell, Paranormal Activity, Orphan, and, expanding the boundaries of the category a touch, the sensationally creepy Coraline. Now, in 2010, there’s no such luck. We’ve had silly Splice (which has its defenders, I suppose, but which seems to me a half-baked Cronenberg riff with ten too many unintentional howlers) and the momentarily effective if forgettable Frozen (which requires a little category expansion itself). For me, the jury is still out on The Last Exorcism, though it appeared to be promisingly low-fi. Otherwise, there was a bunch of stuff not a lot of people seemed to see or care much about: The Crazies? My Soul to Take? Hatchet II? (By the way, what and when exactly was Hatchet I?) It’s perhaps worth mentioning that Shutter Island was as close to horror as Scorsese’s come since Cape Fear, though its impressively Grand Guignol atmosphere got drowned out by its somewhat tasteless reliance on real-life horrors to help boost its dramatic credibility (not to go into detail, but let it just be said that Rivette’s famous abhorrence of The Tracking Shot in Kapò could never have compared to the outrage he might feel if he saw Scorsese’s own tracking shot down a line of Holocaust victims as they’re being machine-gunned to death…but I digress).

Horror moviemaking this year has been frightening indeed (and I’ll happily refrain from any particular sociopolitical diagnosis—there’s still the same mix of torture porn and slasher remakes from any other recent year). So I can think of no better way to start this lineup of Pumpkins than by getting almost as far away as possible from 2010—all the way back to 1922, in fact, to F. W. Murnau’s still chilling chestnut Nosferatu.

Why revisit this oft invoked, screened, and studied adaptation of Bram Stoker now? Well, because I had the pleasure of taking it in this weekend at the glorious Loews Jersey Theatre in Jersey City, one of the country’s few remaining movie palaces. Renovated and reopened by a nonprofit volunteer organization almost ten years ago, the monstrously beautiful movie house has remained something of a nicely kept secret; the audiences for their monthly film screenings have been ever growing in size but have remained exclusive enough that there’s a palpable camaraderie amongst those who show up. Though the 1929 entertainment temple has been made once again into a usable event space, it still feels like it’s filled with phantoms. Bedecked and gilded with detail in every gorgeous nook and cranny, the Loews Jersey is inviting yet austere—its chandeliers glisten majestically above, almost taunting visitors with the luxuriousness of a bygone era; mirrors surround the second-floor balcony landing, so that one might see figures passing from the corner of one’s eye wherever it may dart; the haunting pipe organ blasts ominous entrance music as audiences shuffle in from the ornate lobby to their seats. All in all, an absolutely appropriate place to watch Murnau’s iconic work of expressionism, grasping out at us as an apparition from the dark ages (of movies). Even if this particular Loews Jersey outing felt considerably less hush-hush (recent publicity, including a Village Voice choice in their Best of New York issue, resulted in a huge turnout), the ghostly quality of the place, its intense blast of nostalgia, and the resplendently ominous live organ accompaniment contributed to an extraordinarily uncanny viewing experience.

Despite the richly evocative surroundings, it’s the film that remains most bewitching of all. Nosferatu retains its stark and shadowy dreadfulness, in a way that elevates it above all other Stoker adaptations, whether from Tod Browning, Terence Fisher, or Francis Coppola. Of course there’s the vampire itself, defined by the famously fearful makeup and performance style of Max Schreck as the film’s Dracula figure, Count Orlok—and with his hawklike stare, sharp fangs and talons, and a ramrod-stiff posture that makes it seem as though he’s on a conveyor belt when he walks, Orlok would indeed seem to be an image from the deepest recesses of anyone’s nightmares. Yet it’s also the way Murnau uses that terrifying face and body within each composition; there’s an astonishing use of space in this film, which seems to get lost in the discussion of the film’s sophisticated deployment of expressionist lighting or parallel editing. When we, and the film’s Jonathan Harker character, Hutter, first see Orlok transformed into the evil creature, it’s from an eerie distance, a long shot from the doorframe of Hutter’s guest room in Orlok’s castle. Orlok stands remotely, and spine-chillingly still, his gaze fixed on us and Hutter. We don’t see him move closer, though we know he is approaching; Murnau simply cuts away to Hutter’s horrified expression and fruitless attempts to hide. Then, the latchless door slowly swings open, its impossible creak seemingly audible.

Whether he’s immobile and staring out across the street while clutching a window, rising from a coffin in the basement of a sailing ship as though attached to invisible pulleys, or mounting a staircase in silhouette, claws outstretched, he cuts an intimidating figure, and remains, 88 years on, one of the most effective single moving images ever recorded. This particular incarnation of Dracula, and Schreck’s impersonation of it, are so iconic at this point that his first appearance in the film elicited a round of impassioned, genuinely appreciative (as opposed to ironically distanced) applause from the Loews Jersey audience. The name Max Schreck might not be as recognizable as Bela Lugosi, but it’s the face of the former that will haunt your dreams. Murnau knew in 1922 what so many of today’s horror auteurs don’t seem to grasp—that simplicity can shock. And judging by the audience response to Nosferatu this weekend, many of us still crave that simplicity. Perhaps it’s because what we remember of so many of our nightmares stems less from situations than from single images—usually, in my case, faces. If movies are often reflections of ourselves, then it’s the twisted likeness staring back, mouth agape or grimacing, eyes wide or narrowed, that is perhaps most awful of all. Schreck’s Orlok is not simply a dangerous beast, but something too close to human for comfort. —Michael Koresky

Second Night:

The House of the Devil

“Are you not the babysitter?” For those who haven’t seen The House of the Devil, this is an innocuous question; for those who have, it will undoubtedly elicit shudders of recognition. The line of dialogue comes at a decisive turning point in the film, and instigates the first real blast of violence. That Ti West’s truly frightening horror film is not prone to such explosions—the director is more interested in the emotional toll of creeping terror on the audience—makes that moment, and the words that precede it, all the more disturbing. West proves to be a master of the unexpected in The House of the Devil, but the surprises aren’t the literal events onscreen so much as how he manages to withhold information and traditional scares without creating an iota of slack.

The House of the Devil is two things, successfully, neither of which is easily pulled off: a sustained exercise in minimalist tension and an uncanny eighties nostalgia trip. That these two modes don’t cancel each other out is something of a minor miracle, or at least announces the official arrival of a major talent (Devil is West’s third feature). Structurally similar to something like Tarantino’s Death Proof in the way it attenuates suspenseful build-up to drastic, nearly absurd lengths before paying off with bursts of extreme bloody horror (though missing that film’s deconstructionist sophistication), The House of the Devil excels at slow burn. In fact, that’s what most of the film’s 95-minute running time is. The eerily slight plot concerns a beautiful yet prim college sophomore named Samantha (an immensely likable Jocelin Donahue) who accepts a dubious, last-minute babysitting job from the ominous Ulmans (Tom Noonan and Mary Woronov, too perfectly cast perhaps) to find a way to pay the deposit on a new apartment; detailing the rest of the narrative blow by blow would undoubtedly ruin the film’s chief pleasures, which have to do less with what ultimately happens than how it happens, or rather how West shows it to us. He directed, wrote, and, crucially, edited the film, and it’s rhythmically quite sophisticated. Much of the film is preoccupied with watching Donahue creep around the Ulmans’ house like a curious feline, turning lights on and off, peering into doors, looking out windows.

The stretched-out anxiety grows unbearable, and even though we’ve been given clues here and there about what might be going on (the film even opens with a faux-sobering litany of onscreen facts about real-life Satanic cults), West invests the film with enough off-kilter details and odd nuances to keep us on our toes. The House of the Devil has its share of shocking gross-outs and demonic makeup effects, but days later one might instead recall the way Samantha’s friend Megan (Greta Gerwig, a naturalistic breeze here) wrinkles her nose when eating a slice of pizza or a piece of hard candy (food becomes a surprisingly crucial element in the film) or just how light hits a stained glass window on the Ulmans’ foyer staircase. It’s about as elegant as any horror film in the past decade, not least because of its shooting style, employing a host of hauntingly composed slow zooms that gradually penetrate all of the film’s calmly appointed interiors.

Yet this is not another Shining riff: The House of the Devil proudly announces its antecedents right from the beginning—it’s not an homage to Kubrick, but rather to dingy, cheap 1980s American horror movies. Not only is the film clearly set in this particular past (check out Samantha’s trusty oversized walkman, Megan’s baseball jersey, the pizza joint décor) but it also apes the filmmaking style of the era. The opening credits come on in thick, freeze-frame-accompanying yellow font, backed by synth pop: yet just when one’s about to dismiss West’s film as “Wet Hot American Horror,” the singular, sculpted meticulousness of the film’s design (of which nostalgia is a part, but not the whole) begins to provoke and unsettle rather than lull or distance. Homage is simply West’s vessel; the result is genuine, and clearly the work of a director who puts more love into each composition and perfectly timed beat than he does into foregrounding period signifiers (once we get into the Ulmans’ house, the film could be taking place at any time, regardless of Samantha’s high-waisted jeans).

There is indeed payoff to all this delicious dramatic dawdling. If it all happens too quickly, after an impressive period of everything moving so wonderfully slowly, then at least it leaves us wanting more (a surprising response to a film given to fits of sudden excess, perhaps). There are horrifying images in the last fifteen minutes of The House of the Devil (West gets a lot of mileage out of one flashing ghoulish visage), but most memorable is the endless anticipation. Of course, when The House of the Devil was first acquired for release following its festival premieres, distributors suggested West “tighten” his film, quicken the pace, remove some of the slack, in an effort to make it more commercial. West didn’t cave. Let’s hope he continues to stick to his guns; I can’t wait to wait again. —MK

Third Night:

My Dinner with André

No, this isn’t a Waiting for Guffman–style jest. While by no means a horror film, Louis Malle’s My Dinner with André is in some ways the ultimate campfire tale, in which we lean forward and open our ears and minds to a persuasive, grave storyteller who’s at times seemingly bent on raising our hair. Not convinced? Then you haven’t really sat with André Gregory as he recounts his epic Halloween anecdote.

In inimitable hushed manner, Gregory is the ultimate yarn-spinner, talking in dulcet, yet subtly self-amused tones, leaning forward in his seat to beckon his table mate Wallace Shawn (and us) ever closer. Gregory says a lot in the course of his epic Upper East Side restaurant conversation with Shawn; so much that it often feels more like a monologue—fitting for a theater director, perhaps. But of all the choice, exotic experiences this garrulous, birdlike man assaults his companion’s ears with, perhaps none made more impact on this viewer than his relation of his Halloween night on moonlit Montauk. Ever the name-dropper, Gregory casually mentions that this gathering of nine or so people (“mostly men,” he emphasizes) took place at the wilderness surrounding the home of Dick Avedon there at the tip of Long Island, which he describes as “like Heathcliff’s property.” Surely, Gregory must been in the same New York art circles as iconic Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and New Yorker photographer Avedon, and My Dinner with André, borne out of Gregory’s real experiences trying to find the spiritual in his life, was certainly partly autobiographical, so is the following story true?

It seems too fanciful (and elaborately terrifying) to be so, but Gregory paints it with such vivid, frank passion that I choose to assume that it did happen. For four minutes—in an unbroken shot—Gregory is nearly shaking as he describes his tale. This is no mere pumpkin carving party: the gathering of invitees (presumably of the Manhattan art and theater elite) found that over the course of a few nights, three of their party kept disappearing, and that it soon became clear that something grand was in the works. Finally, at midnight on Halloween (or, as Gregory also calls it, “All Souls Eve”), the remaining guests were beckoned to a cliff, naturally “under a full moon.” From there, Gregory explains, his voice slowing and lowering with quivering, dramatic flair, they were led to the basement of a burned-down house near the property. Inside, a table had been prepared, laid out with papers, pencils, and wine; here they were ordered by their hosts to write down their last testaments. It’s clear that this Halloween celebration was intended as a confrontation with death.

Soon Gregory is blindfolded, then brought to a room filled with a harsh white light, where he is laid out on a table, naked and sponged, before being led at a brisk pace, sightless, through the cold, still forest. The inevitable comes: he is put on stretcher and lowered into the ground into one of six freshly dug, eight-foot deep graves, his valuables placed on his body, wood covering him, dirt shoveled on top. Then, the point—the resurrection, the release from the earth, the catharsis, the bonfire where everyone was reunited and danced till dawn.

Gregory’s need to be nearly buried alive and reborn is of course just one of many examples of his own maddening narcissism, his unending quest for enlightenment and cleansing rituals (which also took him to the forests of Poland with an experimental theater director, the Sahara with a Tibetan Buddhist monk, to Scotland, to Belgrade). The narrative is chilling, both in its details and its implications about Gregory. From the way he summons them with such sinister skill, Gregory clearly knows his exploits at Montauk ultimately amount to nothing more than a good spook tale. (And how else should Shawn—and we—respond than with a quizzical stare? When Malle finally cuts away from Gregory’s close-up, we can see Shawn’s bemused profile) “I really feel that everything I’ve done is horrific,” Gregory soon states with ease, and while it’s hard to see this statement as anything more than attention-seeking and a form of self-aggrandizement, the impresario’s confessed need to debase himself, body and soul, resonates. There’s a dreadful power to his scary story that hangs over the rest of the film.

Almost immediately after, the quails are served, their little legs sticking straight up. Of course we can’t help but think of Andre on his death slab.—MK

Fourth Night:

The Thing

What makes The Thing really scary is not the special effects. Unlike Phantom of the Opera (1924), wherein all the terror begins and ends with the indelible image of Lon Chaney’s unmasked face (see, in similar vein, Pumpkins III’s treatment of Mr. Barlow in Tobe Hooper’s Salem’s Lot) there are many unforgettable coups de théâtre by Rob Bottin in The Thing by turns disgusting, bewildering, sickening, shocking, and more often than not absolutely hilarious—but not scary. Not really. If anything, these magnificent plastic pyrotechnics operate as a welcome release from what is truly horrific about John Carpenter’s 1982 flopzilla (now cult favorite)—and that’s not knowing what it is that you’re afraid of.

You see, The Thing is not just a clever title. The enemy, a corrosive alien organism which kills and replicates its prey, by its nature has no distinct face or personality of its own—a trite “conquer and survive” motivation is ascribed to it but it defies any description, hence the impotent references throughout to “that . . . thing.” It only exists visually as either a complete replication of one of the characters, or more often a repulsive abortion of its own attempt to do so. Whereas the exact same observation could be made of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, that film was very quick to define the enemy (and its motivation) by reference to a familiar concept of global paranoia. Despite Wilford Brimley’s character being driven mad by the prospect of the Thing incubating and destroying every human on earth, The Thing is really just haunted house drama—the primary aim of each character is his own immediate survival within the confines of an Antarctic base, cut off from the outside world by a snowstorm. For this, each character needs to know who he can trust to help him.

But if you don’t know what it is you’re afraid of, then you’re afraid of everything. So once the immediate danger is defined as the possibility that any one might be “infected,” the film becomes a thrilling reimagining of Jean-Paul Sartre’s short play No Way Out, wherein Garcin, trapped in a single room with his two female companions, utters the immortal Sartrean aphorism: “Hell is . . . other people.”

This close-quarters horror culminates in an unbearably tense dialogue/action scene wherein MacReady (Kurt Russell, who is no more trusted than anyone else, but who has the presence of mind to go first dibs on the flame thrower) ties all the survivors up onto a bench and tests blood samples from each of them to try and trigger a defensive reaction from whichever is the Thing all while the trussed victims bark their innocence, resentment, and fear at him. The satisfaction of the scene, as with so many others in the film, is in the impossibility of the audience to properly relate to any of the protagonists—a gruesome pocket version of Ten Little Indians, where the killer changes into the victim on each occasion.

So what of these “other people”? Here is where Carpenter seems to have stolen directly from Ridley Scott’s Alien, by having his cast of characters comprise a group of ostensibly tedious scientists. They are as far removed from the genre stereotypes as possible, but Carpenter takes it even further: respected theatrical character actors Richard Dysart, Donald Moffat, and Peter Maloney are amongst the nerdlingers easily brushed aside by MacReady when it comes to getting serious about killing the Thing. Though these straight batsmen, like Gregory Peck in The Omen, seem meant to add credibility, they will all be violently (and delectably) transformed into some of the more repulsive entities in horror cinema—the graphic implausibility operating as comic relief from the taut cheesewire atmosphere of distrust and fear. As Thomas Waites says when Charles Hallahan’s disembodied head grows arachnoid legs, turns upside down and scuttles out of the door in silence while the others simply watch: “You have gotta be fucking kidding.”

The Thing ultimately represented for Carpenter the opportunity to throw onto the screen what Halloween’s restricted budget forbade him. And just as a cash-strapped Carpenter devised an apparently omnipresent ghost in Halloween (Michael Myers is a now-you-see-him-now-you-don’t creature of the shadows, who could strike from anywhere), so in The Thing, the same claustrophobic sense of present danger is more terrifying than any special effect. —Julien Allen

Fifth Night:

The X-Files: "Home"

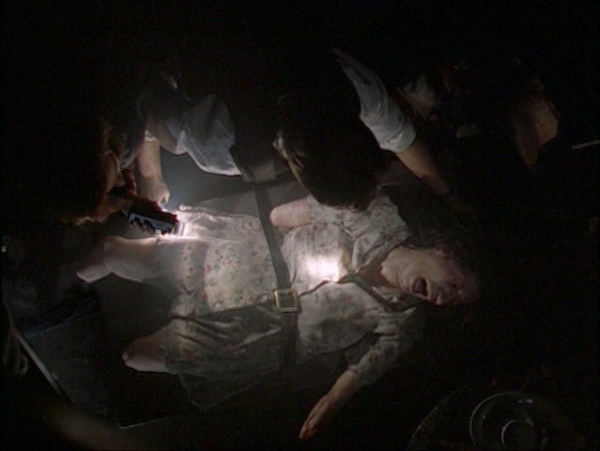

It’s all about that cold open. The camera drifts down through darkness, as Mark Snow’s feverish score plays in the background. Then thunder cracks and lightning illuminates a house in the distance through the rain. An axe or scythe is perched on a barrel in the foreground. The next cut takes us inside the house to a close up of a screaming woman. In the lowest of low-key lighting, male figures tend to the woman, grabbing an object (a knife or scalpel?) from a bowl. Lightning flashes, and then there’s a squeal. We see the men cut an umbilical cord, and we hear a baby gasp, struggling to breathe. The camera cuts outside, near the floor of the porch, and three pairs of feet walk past. The men walk to a field and dig a hole in the ground, as one of the three cries in the background. They place the baby in the hole and begin to fill it. Then we get a point-of-view shot from the baby’s perspective as the mud is shoveled on top of it. The two men console the third. Cut to credits.

I first saw that cold open to the X-Files episode “Home” when it aired in 1996, and at the time, it was probably the most disturbing thing I’d ever seen on broadcast television. And then it got worse. After the commercial break, the episode, written by Glen Morgan and James Wong and directed by Kim Manors—a crackerjack team by X-Files standards—returns to Home, Pennsylvania, as a group of boys start a baseball game in the field next to the same house we saw before. After a ball flies over the fence, to the yard in front of the house, the right fielder who refuses to retrieve the ball identifies the lot as “the Peacock’s property.” So the kids find a new ball. The batter rubs his hands in the dirt, taps home plate, and begins to dig his feet into the ground. Suddenly, his foot kicks up a pool of blood, and the baby’s hand becomes visible.

Perhaps this imagery is no more grotesque than what audiences might now see on a typical episode of CSI, but it caused quite a stir back in 1996. After its first broadcast, the Fox network refused to rerun “Home” because of its incendiary content. The episode’s incestuous mutants may have been the cause of the ban, but my money’s on the dead baby blood. As revolting as those opening images are, though, for the most part, the plot of “Home” just recycles some familiar generic tropes—a family of inbred, deformed Southerners (when it comes to horror, is there any other kind?) kill their deformed infant, then a few people who try to meddle in their business—and the body count is fairly low. What makes “Home” so effective and affecting isn’t so much its audacity as it is the elegance of its construction.

Like the best monster-of-the-week X-Files episodes (and this is certainly among them), “Home” terrifies because its writers and director demonstrate a perfect command of the mechanics of genre. Morgan and Wong’s script delivers an immediate shock and builds to its climax through a perfectly paced 44 minutes, while Mulder and Scully (David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson) piece together the wretchedness of the Peacocks’ condition one scene at a time, bringing a welcome levity to diffuse the overwrought proceedings. Manors, meanwhile, deftly deploys long shots, close ups, obscure angles, and low-key lighting to convey the threat the Peacocks pose while delaying the reveal of their monstrous appearance.

The episode culminates with the grand entrance of Mrs. Peacock, a multiple amputee who rolls across the floor and under the furniture on a low, four-wheel dolly. She is a pitiable and hideous creature, a monster just recognizably human enough to be truly terrifying. Forget the sewer fluke or the tumor eater; Mrs. Peacock may be The X-Files’ single most memorable one-off creation. After meeting her once, who needed a rerun? —Chris Wisniewski

Sixth Night:

Empire of Passion

When an established auteur breaks away to make his or her first—and in many cases, only—horror film, watch out. Film history is full of such instances, from old masters (Clouzot’s Diabolique, Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf, Kubrick’s The Shining, and, to a certain extent, Pasolini’s Salò) to contemporary art-house arbiters (Claire Denis’s Trouble Every Day, Bruno Dumont’s Twentynine Palms, Lars von Trier’s Antichrist); these are films in which the director’s concerns don’t get displaced but rather find a pure outlet of expression. Utilizing horror tropes can give filmmakers free reign for extremes, whether in terms of extraordinary content, stylistic flourish, or, of course, violence. (Don’t we wish Bresson had made a horror film? I suppose L’Argent does come awfully close…) One of the great one-off horror auteurs is surely Nagisa Oshima, although considering the way it was marketed for years, his 1978 Empire of Passion has not long been widely known as the gruesome ghost story it is. Consistently paired with In the Realm of the Senses (even released here as In the Realm of Passion), Empire may have contained echoes of that prior film’s obsessive, destructive eroticism, but it’s a different beast altogether—a kaidan about supernatural vengeance.

It may still come as a surprise, then, to even some of his admirers that Oshima—iconoclastic, fiercely political Japanese New Wave groundbreaker—made a horror film at all. Throughout the 1960s, Oshima was solidifying his stature as an artist working resolutely outside of the studio system, constructing difficult, idiosyncratic movies that explored such pet themes as carnal desire, death, the failure of the left, and his country’s attitudes to race; strong, unsettling works such as Pleasures of the Flesh, Death by Hanging, Japanese Summer: Double Suicide, and Violence at Noon all contain extreme elements that would feel right at home within horror, perhaps, but which functioned within noirish or absurdist frameworks. By the time he made Empire of Passion, following the cause célèbre of the hardcore In the Realm of the Senses, Oshima had become a globally renowned name in art cinema, and like that previous film this was another international coproduction. But neither of them show signs of compromise—in fact, though narratively more accessible than his more experimental works, Empire of Passion contains some of the director’s rawest, most brutal imagery.

Unfolding like a Meiji-era Postman Always Rings Twice, Empire of Passion (its original title, Ai no borei translates as “Love’s Phantom”) transitions from an erotic, explicit tale of amour fou to an eerie, nightmarish creepshow, yet one that defies easy categorization. The film contains risen ghosts seeking revenge, thick mists, brooding specters, and deep dark holes in the earth dug for the purpose of hiding corpses—yet Oshima wasn’‘t interested in creating a mere spook story. This is a gripping evocation of rural desperation and village life at the end of the nineteenth century, as well as a truly unsettling depiction of crime and punishment. In it, Seki, the wife of a simple rickshaw puller named Gisaburo, murders her husband with the help of her amoral younger lover, Toyoji. Their ecstasy is temporary: their feelings of guilt manifest as Gisaburo’s wicked, dead-eyed, sometimes bleeding ghost, who eventually not only frightens and haunts the couple but takes physical revenge on them.

Empire of Passion may not be a traditional horror film, but some of Oshima’s imagery is unforgettably horrific, including an ultra-stylized midnight ghost-rickshaw ride and a climactic sequence in which Seki and Toyoji are trapped in the well where they threw Gisaburo’s corpse, only to be showered with dirt, leaves, and twigs, one of which pierces Seki’s eyeball in close-up, Fulci-style. Nevertheless, what makes these moments so shocking is that they feel like genuine disruptions to the fabric of the film, which is more a clinical study of domesticity and a dramatic evisceration of two people haunted by some seriously bad decision-making. Whereas in a true genre film, a director will hit certain expected beats, Empire of Passion‘s shocks often truly come out of left field, and leave the audience woozy. Ultimately what makes Oshima’s film so disturbing is the pity the director feels for the dead and the pitilessness with which he views the living. Gisaburo is a melancholy, wandering spirit, but his murderers are far worse off, living in a state of constant permeating dread. —MK

Seventh Night:

Rosemary’s Baby

The history of horror cinema is besotted with effective scares, unimaginable scenarios, gallows humor, effortlessly eerie performances . . . but how many films of the genre can claim perfect storytelling? A great many of even the greatest are cursed with sputtering storylines, even the most epochally frightening among them designed as machines lurching ahead to the next great gotcha set piece. Are we watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for the interstitial moments between massacres? Halloween for the little connections its flat characters make amidst Carpenter’s careful, classical compositions? Are we invested so much in the lives of Regan and Chris MacNeil that we would happily forgo The Exorcist‘s roller-coaster second half? Are the kids in A Nightmare on Elm Street multifaceted enough that we care about them before they’re eviscerated? Rosemary’s Baby is one of the few horror movies I can name that is so compelling in its minutiae, so perfectly structured, or sculpted, rather, and most importantly, such a completely realized portrait of recognizable humans caught up in a bizarre situation (from its hero to its many villains), that by the time its characters’ idiosyncrasies have been revealed as indicative of something far more sinister, we’re already emotionally invested enough that we dread rather than crave shocks.

As most agree, Roman Polanski’s effortless masterpiece perfectly mixes a paranoia thriller with the supernatural Satanic, while creating cinema’s most disturbing, persuasive pro-choice narrative (the true horror of the film comes from young Rosemary’s lack of control over her own body, which has been corrupted by nearly every person around her). What makes it special is in the telling: Polanski’s casual brilliance with narrative and space is matched by his adeptness at screenwriting here. With a few elegant strokes, entire back stories are sketched: Rosemary’s Catholic upbringing is portrayed only through abstracted dream sequences and her obvious discomfort at an anti-pope dinner party conversation; her husband Guy’s narratively crucial out-of-work-actor desperation not belabored upon but taken as a sly given; and Polanski wisely allows the creepy next-door Castevets to be almost wholly defined by the amusingly eccentric behaviors and mannerisms of Ruth Gordon (fussy, fidgety, nosy, aloof) and Sidney Blackmer (self-righteous, self-amused, with a piercing stare). These people (including Rosemary’s dapper elderly friend Hutch) are individually fascinating enough to each warrant their own film; all are utterly different in decorum, and their neuroses and needs bounce off of each other with ease.

The most terrifying character of all is Guy’s. It’s tempting to wonder what Robert Redford, originally courted for the role, might have brought to this ultimate egotistical actor, with his golden boy deadness, but there’s no doubt that the role is now unthinkable without John Cassavetes. With his devilish handsomeness (one second youthful and penetrating, the next gaunt and soulless, always with expressively arched eyebrows), he certainly looks the part of a villain, in this case a monstrously selfish husband who sells his wife (and her body) down the river for his own future; but unsurprisingly Cassavetes brings so much more to the role, underscoring Guy’s every action with a shocking degree of contempt and self-loathing. Whether or not some of this characterization sprang from the actor’s own famous discomfort with being directed by Polanski (Cassavetes often looks as though he wants to pounce out of his own skin), the result is a terrifying act of constant disdain. Guy (such an indistinct, nameless name!) clearly hates no one as much himself: if there even is such a thing as happiness, clearly everyone around him is a roadblock—especially Rosemary, as it turns out. He clearly despises her simply for being, and once Guy has arranged with the Castevets to have her impregnated by Satan, he only finds her even more repulsive, unable to touch her sexually or even otherwise, naturally recoiling from the child in her womb when she encourages him to feel its kicking.

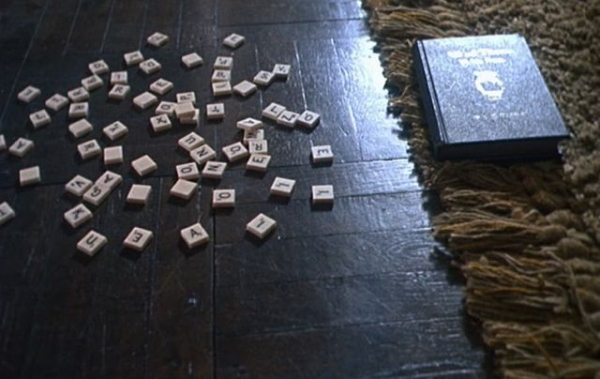

“ALL OF THEM WITCHES,” reads the title of the book (and a fruitless Scrabble anagram) the ever suspicious Hutch bequeaths to Rosemary before his untimely death, and Guy is certainly among them. Polanski’s brilliant stroke to also put Cassavetes in Rosemary’s nightmares as a heavily made up, beastly Satan cements his image as one of cinema’s great devils. And if Rosemary’s defiant final punishment of Guy (to silently spit in his face) seems a mite too small, consider that it’s probably the best she could have done: remember, you can’t beat the devil. —MK