Here Comes the Son:

An Interview with Steven Bognar (Personal Belongings)

By Asha Phelps and Jeff Reichert

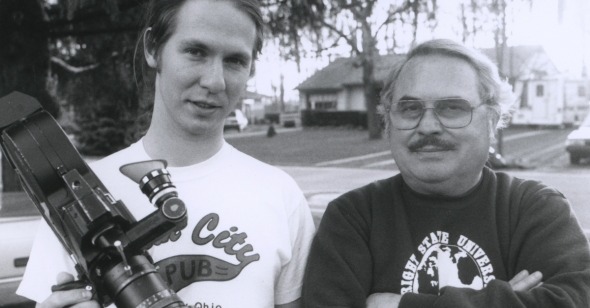

Academy Award–winning Ohio-based filmmaker Steven Bognar is best known for the overwhelmingly empathetic observational films he codirected with Julia Reichert, such as A Lion in the House and American Factory. But before he and Julia became filmmaking partners, Steve embarked upon a near-decade-long odyssey that became his first film, a documentary about his dad and mom and himself and the end of the Cold War—among other things—called Personal Belongings. That film premiered at Sundance in 1996, then screened on the PBS nonfiction series P.O.V., but hasn’t been widely available in decades.

On the occasion of the film’s recent restoration, Steve’s niece and nephew, programmer Asha Phelps and RS co-editor Jeff Reichert curated a 24-film showcase of first-person documentaries from the 1990s for Museum of the Moving Image. They spoke with Bognar about the extended making of Personal Belongings, how it shaped him as a filmmaker, and just how exciting that moment of documentary really was.

The series Personal Belongings: First-Person Documentary in the 1990s starts this Friday, September 20 and runs through the September 29 at MoMI.

Asha Phelps: The title Personal Belongings so adeptly seems to hold the experience of watching the film. We obviously like it so much that we used it as the name for the entire series, but I wonder if you could talk about how you landed there.

Steven Bognar: I had a list going for years, and I would share options with Julia Reichert, my partner at the time, but not my filmmaking partner, not yet. A lot of them were bad. Some of them were okay. One that was sort of half not terrible was Homeward Son because my father was a son of Hungary looking for his home. That was a title I could use to apply for grants. Later, I had a title that was quite bad: Gone, Daddy Gone.

AP: …wow.

SB: Yeah, or Long Gone Daddy from a line in Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA.” I still have that list somewhere; it's one of those things you just keep. So, in the seventh or eighth year of making the film, fairly near the end, the title Personal Belongings popped into my mind while I was in the edit room. I wrote it down on a piece of paper and walked over to Julia, and I didn’t say it out loud because most of us read titles first and shared it. And she nodded and she said, “Yeah, I could see it.” It does seem to resonate with displacement, the loss of home. What you carry, both inside of you and outside of you, when you lose your home, or leave your home and family, too.

Jeff Reichert: I wonder if you could talk a bit about how this became your first movie. Tell us a little about the convoluted road to making it.

SB: In February 1986, I realized my dad was going to go back to Hungary for the 30th anniversary of the Hungarian Revolution, after which he left the country. This was huge. It wasn’t permitted to be celebrated because it was still the Cold War. I immediately thought that this could be a film. Sometimes we overcomplicate things, and later you realize the simpler solution is the better one. My dad had three high school friends with whom he had gone through his youth and the revolution with. My first concept for making a documentary was about these four friends and how their lives turned out. I wrote that out on a piece of paper, weaving their stories together. But the immediate job was: film my dad.

So, I started thinking: “How do I do this?” There were these gurus of Super 8 in the ’80s and ’90s, Bob Brodsky and Toni Treadway. I was living in New York, and I thought, I’m gonna call Bob and Toni. I didn’t know them, but they took my call and they gave me all kinds of advice about how you could get a Super 8 sound camera, and put a baffle made out of carpet and Velcro around the camera. They told me to get a Sony Walkman pro and a lavalier mic at Radio Shack for 50 bucks. I had no money, and it was gonna cost me a lot to just go to Hungary. I bought a Bogan tripod, which I still have to this day and it's very dear to me. And I just started building my kit up and planning on how to do it. In October, we went to Hungary, and I brought 40 rolls of Super 8 sound. The anniversary of the revolution is October 23rd. It's a date that you just know if you’re Hungarian. We filmed all over Budapest and we were stopped repeatedly by plainclothes police. My dad knew he would be stopped, but he was an American citizen and so was my mother. They took our passports, and they wrote shit down and they didn’t arrest us, they didn't try to take the footage, which I was braced for. And then, when it was time to leave, I just thought, “Okay, it’ll be okay.” And I stupidly took all the footage with me, and it was confiscated on the train.

That was really crushing, and I was so ashamed that I didn't think it through. And also I put my Hungarian family in danger. I can still picture the ash in my aunt's face. She said, “You're gonna leave, but you put us in trouble. Whatever you're doing, it could really get us in trouble, and we live here.” As a documentary filmmaker who tries to be mindful…I mean I could not really call myself a documentary filmmaker then, I was a dumb kid with aspirations, but that just like it hit me like a punch. Fuck.

AP: It must have seemed like the film was dead.

SB: I just thought I'd lost the film. I was sort of done. But as you see in the film, my dad was so mad that he just started this slow and steady campaign of calling our senators, calling representatives, trying to put pressure on to get our footage back. I wasn't filming that at first, but then, my smarter friends like Julia and Bob and Toni advised me to film this limbo, film this process, because you just don't know, it could be pertinent. I resisted but I did start documenting, and I'm really glad I did because of course they were right. And it became part of the story.

In spring of 1988, I got an Ohio Arts Council Grant for five or ten thousand dollars. I also got a National Endowment for the Arts regional fellowship for emerging artists. It was like three thousand dollars. This was huge. The moral support, the boost of confidence was so big. And then, of course, all the changes in Eastern Europe started happening. Suddenly the Cold War was ending. I knew it was off to the races.

JR: Watching it again today, I was thinking about how the finished film carries traces of those other films that you could have made—the one about the four friends, the one about your dad’s journey home, the historical document of that moment in 1989. How did you eventually reckon with all your strands and wrestle them into this movie? Thinking about the timeline, it wasn’t until 1996 that you finished, so was most of that time editing and shaping?

SB: I really thought after the Berlin Wall fell in the fall of 1989, that the movie was almost over. And then in the spring of 1990, my parents went back to Hungary. You see it in the film. And they're going to a democratic Hungary and my dad was so proud and happy. That shot where they're getting on the plane and my dad's waving, I thought that would be the last shot of the film. And I literally held that shot of just the door for another two minutes imagining that this is where the credits would roll. Pretty soon after, my mom and dad started having trouble in their marriage. And yet, I'm editing the film that ends happily at the airport where he's waving and getting on the plane! At some point you tell yourself, it's okay, this is my film, not real life. But I had to hit stop on the Steenbeck and say, “This is not working. It's not true anymore.” I told my dad, and then my mom separately, that I needed to include what's happening with their relationship. Because it's otherwise not a true film. That was hard. They did not sign up for that.

AP: And it raises a whole extra level of ethical questions.

SB: Everything in documentary filmmaking is an ethical question. Every placement of the camera. Every question you ask or don't ask is an ethical choice. But the hardest choices are made in the cutting room because that's when you really are saying, this will be seen by the world. You need to edit the best film you can before you show it to the people in the film. So that you've made your best case and if people object to something it's not because you did a lame or half-ass job. Number one. And number two, so they don't lose confidence in you as a storyteller.

JR: But your subjects ended up being your Mom and Dad.

SB: I arranged to show it to my dad on a VHS filmed off the Steenbeck, And then later my mom. My Dad…it's funny: he liked the parts he liked and was willing to kind of not get upset about the parts he didn't like. For my mother, it was really hard. I know I was asking her to endure some real pain. And she said it was a good film and that she never wanted to see it again. It was a very generous thing for her to say, given how personal and how painful it was.

AP: Let’s go back to shaping the film, because I think the process you undertook is pretty inspiring.

SB: I started editing in 1988. I started cutting clips for fundraising in 1989. And then I had a first cut. It was a big mess, and I didn't know what I was doing. I was 26! Julia was supportive, but she was not sitting with me in the edit room. For almost two years, I was trying to figure out the structure, the flow. Would I be a character in the film? Did I need to start writing myself? Not as a neutral narrator but as “Steve the Son.” You watch the film now, and it seems like it just kind of unfolds. But of course, it was not always that way.

I’ll never forget July 4th in 1992. We did the first rough-cut screening. Julia could see that I was floundering in the edit room and just not making decisions, rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. She knew the film was a mess and not really a film. It was the worst rough-cut screening ever. And at the end, I realized the audience was just confounded. I'd already been working on the film for six years. I was crushed, and yet it was essential to the process. And after feeling terrible for a week or two, I realized this was really good and I had a lot of work to do, and then I got down to work, and for the next three years I cut the film.

AP: And you eventually submitted to Sundance...

SB: In the fall of 1994, I thought I'm rounding the bend and I'm gonna submit. As soon as I submitted it, I thought it was a mistake. It wasn’t ready. So, I actually did something I don't even know if you can do anymore: I called Sundance and I said I want to pull the film from consideration. And then I worked on it for another six or eight months. I had a small team doing all the sound work and clean-up work and going out and recording Foley. Georgiana Gomez did the original score, and it was beautiful to work with her. And then it finally became a film.

In the summer or early fall of 1995, I went to the IFP market. Younger folks won't remember this, but the IFP, which is now Gotham, used to have this insane carnival every August or September for all the indie films in the pipeline that wanted to get eyes on it for a festival programmers and buyers. And the Angelika in NYC would become a zoo of people dressed as space aliens or nuns with dildos passing out truffles. The film got some attention and then I submitted it to Sundance.

I premiered it there along with half the films you're showing in this program! I remember meeting Ruth Ozeki and watching her film Halving the Bones there. Troublesome Creek is a wonderful movie and should really be seen again. A few months later, Thomas Allen Harris and I met in San Francisco. His film Vintage was showing and we were both lucky to win Golden Gate Awards. In the summer of ’96, I met a young filmmaker named Alex Rivera at the Flaherty Film Seminar where our films were shown together. His film, Papapapá, about his immigrant dad, was 30-ish minutes long. My film turned out to be 63 minutes, a ridiculous length for any practical purpose, but those two films make a nice 90-minute package. Alex said we should go on the road with these, and he came up with this great name: “Papapalooza,” because Lollapalooza was, of course, a big thing in the ’90s.

Some of the films you are showing in this series were deeply important to me while making Personal Belongings. One of the things my film needed was a voice and a tonal style. This is a film about a guy who had no impact on the world. So why should we care? No one ever heard of him. Why should we watch it? And I would watch films like Lise Yasui’s Family Gathering and Su Friedrich’s Sink or Swim, both of which are part of the series. These were family docs that were so stylized and so thoughtful. I saw a lot of them at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, where sometimes the filmmakers would come. And then I would find a way to get a VHS or something and watch them again and again. So many of these films of that era were just creatively playful in a way that I don't feel like we see so much anymore. Or maybe it's harder to be so bold because there are commercial considerations.

AP: Can you talk about the restoration, both the practical decision to take on the restoration work, and how this may have changed your relationship to and with the film and your dad?

SB: The film had a good life in the world in 1996, ’97, ’98, and my dad felt, ultimately, very good about it. After it premiered, my dad sat me down and gave me a lecture. He said, “Okay, you have made the film. Now you need to get serious about your life and your profession and what you are going to do, and you need to go to graduate school. so you can get a teaching job.” I realized he had been saving up that lecture for years. And to think of that, that’s actually a wonderfully generous thing. When I was lost in despair over the movie…floundering, he waited until it was done.

Any documentary has a life out there in the world that tapers off, and it gets quiet. For a while, the film lived on VHS and 16mm, and that's it. And then in the early aughts, I started thinking I should make a DVD, but by then Julia and I were making A Lion in the House, and we were helping our friend Ed Radtke make a feature film called The Dream Catcher, so the idea of making a DVD of Personal Belongings just took a back seat.

Five years ago, I just started to think, okay, what would it take to restore this film? And I realized all the footage would need to be retransferred and scanned in 2K. So, I had all the Super 8 transferred and then I had all the 16mm, not the raw footage but the master positive DuArt film lab had made. All the subtitles had to be redone because they’re hard to read in the original, and a wonderful young filmmaker with whom we would work on American Factory named David Holm took it on himself to literally work frame-by-frame, line up, and then retype the subtitles in Photoshop and recreate the whole sequence. We rebuilt the visuals of the film step by step, and it took months to do that.

The original sound mix was done by legendary mixer named Rick Dior. He won an Academy Award for Apollo 13. This is where the genius of Julia Reichert comes in. She wanted to get a good mixer. And she was asking around and Rick Dior had a week off between major Hollywood movies and she got him on the phone, and, in a way that I can only imagine Julia could do, she talked to him about this film: “It’s gonna be a great documentary. It's so personal.” She sold this master mixer on how it’d be a three-day mix and he’d still have two days off between big films.

For the restoration, I found a stereo mix of the film on a Betacam SP master tape that sounded pretty darn good. And so that's what we used, and my friend Chris Barnett who mixed American Factory took my stereo mix and spent days on making a 5.1 surround sound mix. And it sounds immersive and I’m just so grateful to him for having done that. Now, the film can finally live both as a DCP and in a high-quality QuickTime.

JR: So, you started making this movie when you were 23 years old. You're now 61. You’ve made a bunch of films. How does it feel to look back over that all and place this movie?

SB: It’s a great question because in a way, this film is an anomaly. It’s a first-person movie where my voice is really in it. And I crafted a character named Steve. My later films don't have that. The films that Julia and I made or my shorts that I made on my own they're just very different. But I think that's fine. I'm not a kind of filmmaker who feels that you have to feel the formal through-lines from film to film to film. Cinema is the biggest playground, and I do feel documentaries, especially, should embrace all kinds of ways to play with narrative and with visual technique.

The nine years it took to make the film was how I became a filmmaker. It was my forge. I am a different person on the other end of making that film. I look back to my 23-year-old self when I started making the film and how exuberant and utterly stupid I was. How naive but full of gumption and guile or I don't know what. And then there’s the 32-year-old who premiered the film at Sundance, who had been crushed again and again and had gotten through it.