Wild America

by Jeff Reichert

The Illinois Parables

Dir. Deborah Stratman, U.S., Grasshopper Film

As evidenced in her latest feature, The Illinois Parables, Deborah Stratman hasn’t much altered her strategies for historical filmmaking from those she employed in O’er the Land, her 2009 post-Bush gloss on national (in)security and militarism. Thankfully. In both films, Stratman, a one-woman filmmaking army (she’s credited as director, cinematographer, producer, editor, and occasional sound recordist), exhibits a knack for choosing historically significant locations and then, through careful framing, the addition of the right sounds, the introduction of primary source texts and other unexpected choices, she slowly unpacks the history of the place we are looking at. She seems drawn to scenes that put the present in direct dialogue with the past, and the fictional in competition with documentary, as in O’er the Land when, after showing images of a group of men in colonial uniforms waging battle in the woods with muskets, she cuts to their audience, arrayed in bleachers and wearing present-day clothes. What we first might have assumed to be a historical fiction staged for the camera is revealed to be an “actual” restaging of a different sort for different aims.

One of the first scenes in The Illinois Parables works similarly. It features an ancient, massive Cahokia burial mound pictured from a few angles. There are no traces of modernity at first, so it startles somewhat when Stratman pulls back to reveal the white painted lines on asphalt of a nearby parking lot. Not long after, shaman Raven Wolf walks through her frame drumming and chanting an indigenous song (he’s far from the camera, but the closeness of the recording reads as intimate), and then gaily introduces himself to the camera. In The Illinois Parables, Stratman seems fully unbound by the sense that anything she films need be, in her final assemblage, just as it seems, that by dint of capturing her images in an ostensibly “documentary” mode she is automatically allied with the surface reality of her images.

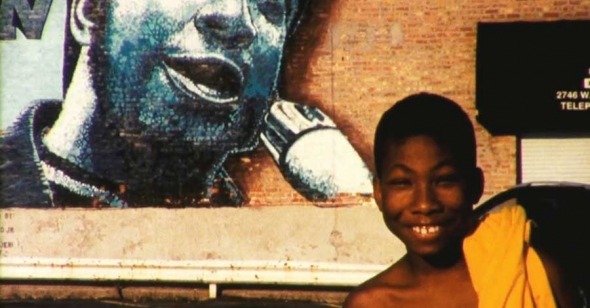

Broken into eleven discrete sections,The Illinois Parables gambols blithely through 1500 years of history, while paradoxically seeming like it never moves at all. Stratman’s camera remains locked firmly in place as it captures the variegated landscapes of the Prairie State at length and her methodology of juxtaposition allows these static frames, all obviously captured in our present moment, to be placed anywhere she likes in history. Shots of a faded museum diorama of native life near the film’s beginning take us back to the 1600s in Alton upon the arrival of the white man. Later, a weathered mural of Fred Hampton is meant to locate us in Chicago in the late 1960s; in this same chapter, the chilling hilarity of her black-and-white recreation of the raid that left the Black Panther murdered, performed by a bunch of deadpan police stand-ins, strikes a complex contrast with the young black boy she films in front of the mural in color.

She maintains a sense of free play throughout, even as her film marches resolutely forward through the historical record. Filmmaker David Gatten (The Extravagant Shadows) is “cast” as Ralph Waldo Emerson, and in Stratman’s formal universe, the inclusion of both Gatten and Emerson reads as significant. To retell the story of a tornado that killed hundreds in southern Illinois in 1925, Stratman tracked down witnesses and survivors, interviewed them, and placed that audio over newspaper headlines and sketches of the event. Though each chapter references highly specific histories, you don’t need an expert’s grasp of the material. You might not know who Enrico Fermi was—that he created the world’s first nuclear reactor, that he did so out of the University of Chicago’s Manhattan Project—to glean from Stratman’s combination of sound (Fermi essays read aloud) and blueprint and technical sketch imagery that Illinois played some role in a major scientific breakthrough.

In her personal vision of history, more recognizable events are placed side-by-side with lesser known stories: a decent chunk of The Illinois Parables’ running time is given over to the Icarians, a long-extinguished French-speaking Utopian community. Their home base of Nauvoo in the mid 1800s also happened to be the site of anti-Mormon violence that led to that sect’s exodus to Utah. In uniting the places she’s chosen through cinema, she’s asking us to contemplate the permanence of landscapes that consistently see new communities, new ideologies, new sciences, new enemies of the state, new human disasters. Implacable Illinois watches over all.

Stratman’s works exist in the lineage of landscape documentary that includes James Benning (usually marginalized as simply avant-garde); Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet’s Too Early/Too Late; Varda’s Mur Murs; Kossakovsky’s Hush! But as much as The Illinois Parables may be aligned with this subset of nonfiction filmmaking there’s something to Stratman’s maximalist, skipping-stone approach that’s equally reminiscent of recent fact-based episodic prose fictions such as John Keene’s Counternarratives, which sought to retell the American story (North and South) from the vantage point of its black people, or László Krasznahorkai’s Seibo There Below, which examined ideas of art and grace through a series of globetrotting, history-spanning episodes linked by the Fibonacci sequence. Further back, we might call up William Carlos Williams’s seminal work of resistant history In the American Grain.

With these high-wire works, which seem able to go anywhere and inhabit any moment, there comes a sense that master narratives haven’t served us well—that the ur-text contemplating history from a single angle or perspective only leads its appraiser to a sense of false mastery and fake confidence, that fragmentation and splintered narratives might be more appropriate tactics for inviting awe at complexity and conjuring intrigue around contradiction. Contrast all that’s contained within the brief The Illinois Parables with what little is communicated in another recent cinematic attempt at excavating history, Nate Parker’s execrable The Birth of a Nation. The Illinois Parables is a universe full of U-turns, roads untraveled, curious crevices worth further exploration. Parker’s film flattens out a crucial episode in our national story into a simplistic revenge narrative and presents itself as definitive. It’s a saddening truth of commerce and taste that far more people will ever see Parker’s work than Stratman’s, but I’m hopeful The Illinois Parables will be more remembered by those who see it.

At times The Illinois Parables feels like a movie that could have existed even before movies. This feeling of agelessness is surely abetted in this era of too-crisp digital projection by Stratman’s insistence in shooting and exhibiting on 16mm. As the images flicker and wobble to the tune of the pops and hisses of a never fully silent optical track, we’re brought back to earlier days of cinemagoing, not far distant from us, but ever-receding. A film like The Illinois Parables, whose only agenda is inquiry and discovery, feels necessary right now. There’s something calming and liberating in Stratman’s approach, a feeling that there’s solace to be found for those tuned in. Especially in this moment when so many took easy refuge in a facile idea of our country, its traditions, its problems, and its future, it is warming to come into contact with fellow travelers still reveling in the weird and wild of America, insistent on letting it roam free, and finding forms that fight actively against tamping it down.