The Weight

Michael Koresky on William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take One and Take 2 ½

One of the commonly held wisdoms about digital video technology is that it provides easier, lighter, more affordable access for young filmmakers. In other words, those who are just starting out and who may not have a foothold in the business or a bottomless checking account but who want to get their voices heard—it’s an idealistic sentiment, and not without truth or precedent, yet as the practice of shooting on video has become a more omnipresent, less controversial alternative to film, it’s crystallized that the technology’s accessibility has had wide-ranging effects not only on the industry but also on the techniques of filmmakers of the old guard. The eyebrow raising that met the digital dalliances of Spike Lee and Jean-Luc Godard way back at the turn of the millennium (when Bamboozled and In Praise of Love were thrust into a nonsensical continuum with Chuck and Buck, Tadpole, and their cruddy ilk) now seems an awfully quaint symptom of technological distrust, even if the intentions (and reactions) wildly varied—Godard’s midfilm transition to video was a distinctly gorgeous, color-saturated move as tactical as any stock shift he achieved in the sixties; Lee’s technique was opposite, using video to cast a dyspeptic pall over his film, as though the image had purposely been dunked in raw sewage.

Meanwhile, as we reached the second half of the decade, even more classically trained, legendary filmmakers began to drift toward digital with less public ballyhoo, and rather than wrestling with new technologies, directors such as Robert Altman and David Lynch effortlessly wielded video as a natural extension of their already well-practiced gifts—the former for mobility, lightness of effect, spontaneity, lushness; the latter for texture, pixelation, nightmarish image quality, cheapness. At this point, there’s no longer any fair method for easily categorizing movies shot on video from those shot on 35mm, by cost or point of origin (audiences for Zodiac or A Prairie Home Companion, treated in most theaters to images that have been transferred and blown up from video to film for projection, often aren’t aware they’re not watching a 35mm-filmed image); yet for those longtime auteurs without the cachet of a Lee or Godard, and who don’t come with a built-in audience or established reputation, the use of video for its abilities continues to transform the process of filmmaking, if not reception.

The fascinating career trajectory of William Greaves perfectly exemplifies these issues, in no small part because of his outsider status. A Harlem-bred African-American actor who studied at the legendary American Negro Theater in the Forties and at the Actor’s Studio in the Fifties before turning editor and finally documentarian, Greaves was both an up-and-comer and an industry pro by the time he made his most wonderfully foolhardy experiment, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, in the Sixties. It would be the type of work that might have served as aid for funding of future projects had anyone seen it at the time; yet following years of assembling footage shot in Central Park, in 1968, Greaves never found distribution for his film, and it wasn’t given any sort of public screening until 1971. Even after this, it remained for all intents and purposes buried for decades, turning up here and there to appreciative festival audiences, from Sundance to the Hamptons.

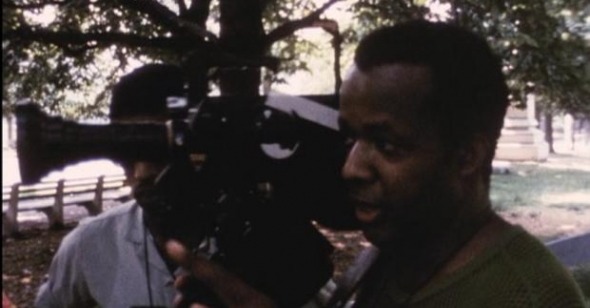

While mainstream success seems a long shot, it’s plausible that Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, with its likeably freeform blending of meta-documentary tricks and avant-garde theater explorations, might have established Greaves as some sort of cult figure earlier in his career—under different circumstances of production and distribution. These days, with his resurgence officially sanctioned by cultural institutions like Sundance and this year’s Full Frame Documentary Film Festival, where he was the lifetime achievement recipient, he’s more prone to receiving veneration; were his gambits sui generis or “ahead of their time”? Coming into awareness of Greaves solely by virtue of Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, one might assume to be witnessing the work of a visionary; yet for all of Take One’s multilayered daring and intellectual heft, Greaves is less idiosyncratic artist than a reliable workhorse with a strong self-awareness. Seen onscreen lugging heavy equipment, often with a burdensome 16mm camera on his shoulder, radiating a deceptive sunniness that masks a canny ability to dramatically manipulate his crew into doubting his authority, Greaves is a technician of the first order—but not “technician” in that oft-used way that connotes a disinterest in content. A craftsman of nonfiction with a multidisciplinary arts training, Greaves wields his self—his professional, racial, artistic identity—and his apparatus with graceful force in Take One; in this self-conscious deconstruction of the group dynamics of film sets, the booms, wires, the slate, and the multiple cameras take on a totemic quality, becoming characters just as much as the crew members themselves.

It’s this focus on the very stuff of filmmaking—the arduous task of getting from here to there, the stock, the grain, the polyphony of on-set voices—that marks Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm project as something of a relic, the sort that would today only exist as an experiment in nostalgia. The film’s insistence on detailing process also makes it more concrete and accessible than its avant-garde pitch would sound: a director, with only the vaguest blueprint of what he wants (outside of a mission statement furnished for his crew before shooting), drags an increasingly confused, disenchanted group of filmmaking assistants through endless takes of badly scripted psychodrama, histrionically acted by revolving-door pairs of actors, in Central Park. Though these intensely contrived conversations, spitted out with pseudo-Albee venom by a hapless married couple named Alice and Freddie, seem more like screen-test outtakes than components of a viable narrative, Greaves appears insistent on constructing them into a workable whole. Unaware that their director has deliberately called his own authority (and, by extension, intellect) into question, the crew, led by the somewhat self-satisfied, but nevertheless invigorated and observant philosopher-cum-sound recordist Jonathan Gordon and exasperated cameraman Terrence McCartney, enact a mutiny of sorts, filming behind-closed-door conversations of their own befuddlement, unbeknownst to Greaves (this footage was given to Greaves after the shoot was over, as he worked on piecing Symbio together in the editing room). The crew’s drama is then intercut with the psychodramas of Freddie and Alice, variously inhabited by performers wildly different in age, race, and delivery (including, in a particularly Stanislavskian moment, two who sing their dialogue to one another to achieve a more expressive vocal intonation), as well as footage of Greaves himself directing his actors with a jocular nonchalance that further alienates the sober-minded assistants surrounding him. Greaves’s demeanor isn’t exuberant exactly, but he emanates an impish delight in experimentation that his collaborators don’t seem able, or willing, to inhale. And they’re necessarily in thrall to this man of whom they’re not necessarily enthralled; inspiration comes to them when they least expect it, however, as evidenced by their oppositional backroom stance.

It’s perception of Greaves’s identity then—as director/commander, as visionary/flibbertigibbet, as African-American—that fuels his filmic subterfuge. Symbio essentially functions as an unspoken sociological experiment and simultaneous avant-garde immersion (strip away easily soluble meaning from a project that seems like it should have strict narrative parameters, and watch the unwitting subjects internally combust or form separate alliances), but Greaves never fails to foreground the tactile, strenuous physicality of filmmaking. The effectiveness of Take One is unthinkable without film itself: the audacity of the effects (split-screen images, little visual riffs in which the picture is contained in alternately enlarging and shrinking boxes) inextricable from the weight and burden of the equipment and the inventive postproduction processes that got them there. Greaves has a camera shooting the crew shooting the actors, so there are always at least two planes of action at any given moment, and the sheer effort of the double tasking adds to the crew’s apprehension about the film’s validity. By the time we get to the main “action” of the film (which Greaves tells some passersby will be called, improbably, “Over the Cliff”), Freddie and Alice have already been irretrievably distanced from the viewer, their over-rehearsed dialogue and multiple performances mere palimpsests, their nattering, implausible viciousness (“You’ve been killing my babies one after another!”) bordering on the satiric. The lasting image in the viewer’s mind of Freddie and Alice is of barely discernible figures far removed from the camera, facsimiles of human beings, fading into Central Park’s greenery; they’re abstracted by the very equipment meant to capture their “truth.” Though playing with documentary form, Greaves heightens their falseness, and in the process makes those working behind the scenes, wielding the tools harnessing this intentionally artificial reality, into the writers of their own narratives.

Thirty-five years later, when Greaves returned to the Symbiopsychotaxiplasm template (he intended to make “Take Two” in the Seventies, yet the inability of the film, barely seen, to accrue a following curtailed that plan), the modes of operation had changed drastically. Documentary-fiction hybrids from unknown independent filmmakers were unlikely to get funding to shoot on film, and, honestly, it now seemed foolish for them to even try. Interest in Symbio had been drummed up again following a 1999 Hamptons Film Festival screening and again at a 2003 Sundance Film Festival revival of Greaves’s work, where the original film had caught the attention of both Steve Buscemi and Steven Soderbergh, the former for its acting exercises, the latter no doubt for its playful meta-trickery. Despite the support of such indie-Hollywood crossover darlings, any follow-up would naturally be relegated to video status. Yet with video’s cost, accessibility, and, yes, weight, the transition was not merely out of necessity or practicality; as the original had done with film, in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm Take 2 ½ the video becomes a character in its own right.

Greaves hasn’t been the first filmmaker of a certain age (he was 69 when he made Take 2 ½) to extol the virtues of shooting with lightweight digital cameras; for every Spielbergian film purist there are seemingly ten others thankful for the less arduous methods encouraged by video. In a recent interview, George A. Romero fondly remembered his experiences filming Diary of the Dead with quick, “guerilla-style” setups and his gratitude for postproduction CG effects, his recollections the musings of an aging filmmaker both nostalgic for his independent roots and relieved that he no longer necessarily has to expend the same physical energy. If there’s a whiff of understandable defeatism in this outlook, it plays right into the visual texture and emotional fabric of Greaves’s Take 2 ½, which, though still assembled from and playing to various layers of cognizance (on the part of the viewers and the crew members), mostly replaces technical and conceptual rigor with casual wistfulness. Greaves begins by shuttling back to the set of the original film, excavating more 16mm footage he evidently would have used in the Seventies had his project continued uninhibited; there’s a good half-hour more of Freddie and Alice’s tortured, unresolved confrontations, yet this time Greaves focuses not on actors Don Fellows and Patricia Gilbert (so shrill in their performances and objectionable in their off-camera personae that they had effectively become Take One’s antagonists) but on a pairing barely seen in the original film, Audrey Henningham and Shannon Baker. And it’s revelatory: rehearsing her lines in a nearly complete run-through while applying makeup, Henningham, in 35-year-old footage, makes Alice a suddenly poignant being, while Baker’s Freddie receives her cross-examinations with patient incredulity rather than arrogant frustration. Aside from the fact that Henningham is the only black actress we’ve seen embodying Alice, she’s also the only seductive, plausible inhabitant of a character who’d been crass and grotesque the first time around. So many years later it’s quite a shock, yet Greaves isn’t merely incorporating deleted scenes, or even changing perception for its own sake; instead, he’s laying the groundwork for Take 2 ½’s singular narrative, which will return to Freddie and Alice, as again played by Baker and Henningham, to more directly investigate the nature of role-playing—a return to Greaves’s early years as a student of acting.

After this first half hour, the original film’s familiar grainy 16mm textures give way to a rather cheap-looking video image of an audience watching the footage in a small, not-quite-filled-to-capacity theater at the Hamptons Film Festival, in 1999. We then see part of a question-and-answer session Greaves conducts with the viewers (with the content and image quality one would now normally associate with a DVD extra), and thus the film’s reception becomes a component of its own narrative, as well as a visual bridge between media. When Greaves rejoins with Henningham and Baker five years later, again in Central Park—this time during the New York City marathon, a strangely, purposefully disruptive and ebullient backdrop—the technology has been slightly upgraded from the home-movie caliber picture quality of the Hamptons Q&A to a more progressively scanned image, shot on a 24fps Panasonic camera. Surrounded by crisp, slightly dulled autumn leaves, Freddie and Alice are reunited after 35 years—and given the foregrounded documentary-like visual treatment (handheld, low-grade camerawork), it takes us quite a while to figure out if we’re watching a joyous reunion of actors or characters. Eventually, we realize it’s the latter, and though Greaves will continue to intercut Freddie and Alice’s story with behind-the-scenes footage (including a useless, overly rehearsed attempt at a second crew mutiny, some technical dalliances of on-set helper Steve Buscemi, and Greaves himself casually straight-shooting with his actors and assistants), Take 2 ½ is more intent on watching these actors passionately try to inhabit these vaguely sketched roles, once again saddled with volatile, emotionally impossible psychodramatic situations.

Though Greaves’s approach in the 2004 segments is hardly conventional, and barely narrative-driven, he uses more commonplace elements to buoy his experiments, such as establishing shots and dramatically inclined shot/reverse shots. Is it the use of video—its mobility, the allowance of endless takes and pickup shots, the cheapness of the tape—that has permitted Greaves to construct Take 2 ½ with more traditional images? In other words, had the burden and cost of shooting on film in Take One forced him to forgo these familiar tropes, relying instead on whatever captured images he could assemble into a somewhat chronological whole? The answers aren’t easy, but that the questions remain testifies to the thin line between invention and pragmatism in experimental filmmaking, as well as the fortuitousness that contributed to Take One’s brilliance and the lack of spontaneity that makes Take 2 ½ more of an interesting oddity than an equally valuable work.

The awkward poignancy of Take One’s ending, in which an loquacious, alcoholic park-dweller stumbles upon the filming location of “Over the Cliff” and proceeds to regale the crew with his life-story, is here replaced with ascending overhead images of the marathon winding through and around Central Park, an event Greaves and his crew must have known would be taking place; the first film’s unexpected moment out of time has been recast with a commemorative moment on a clearly set date. Obviously the method of capturing images will always be subordinate to the nature of the images themselves, while forces of nature (time, age, weather) will remain factors in filmmaking equally crucial to technological advance. Is Greaves’s use of 16mm truly more “gritty” or “penetrating” than the more glib video textures used years later? Whatever the answer, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm provides something of a road map of the development of cheaper avenues of imagemaking, as well as illustrating the limitations of imposing a reading on either film or video as verifiable truth. Finally, Greaves is unburdened, the weight of film, of the past, is sloughed off, and his camera simply rises.