Crossover Appeal

Bob Carroll on Hedwig and the Angry Inch

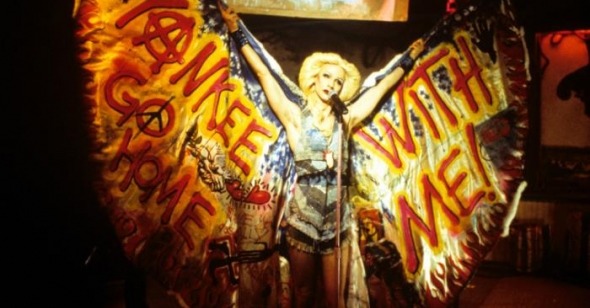

Hedwig hasn’t appeared to cross over. Sure the character crossed the Berlin Wall on a “balloon of love,” crossed the boundaries of gender, barely but spectacularly. But Hedwig never became as iconic, crossed over into the general hegemony, as readers of alt-fashion magazines Dazed and Confused or ID were told to expect. Her harshly made-up face framed by an extreme perm-tastic blonde wig was unavoidable just a few summers ago; Hedwig screaming into a mike, damn near swallowing the thing, was everywhere you glanced. Yet readers of aforementioned publications—and let us remember sometimes it can be hard to find anything that resembles words in these vacant, vague things—have never been interested in making the next big thing actually big. They are live-for-the-moment types, into what is expected to be cool without ever lending their support after they’ve rested their fanny on the bandwagon for 15 seconds. Irrespective of quality, being tagged as hip these days is the kiss of death. Hedwig and the Angry Inch may be trashy, camp, messy but it is quality. It’s just remained a cult thing. And considering its origins, that’s probably for the best.

A chance meeting between theater actor John Cameron Mitchell and punk band Cheaters bassist Stephen Trask set in motion a project to perform rock monologues. The character of Hedwig, a drag performer touring America, who, between songs, reminisces of her childhood in Communist East Germany, her romances, and her botched sex change operation which left her with the eponymous angry inch of penis, debuted and developed during lip-synch amateur nights at New York club, Squeezebox. This was kind of revolutionary in its own right. Drag acts were generally men in dresses doing glorified karaoke routines; Hedwig was a full-blown vaudeville routine with jokes, drama, and a repertoire of innovative punk and funked-up ballads. Most of these survived through to the play that Hedwig metamorphosed into, a one-man show that became as popular as an off-off-off Broadway show possibly can. Much of Hedwig’s catty asides, thrift store innuendo, and, most importantly, punk-infused showtunes survived to form a rock opera which emphasised the Cold War origins and immigrant narrative as much as the gender and sexuality aesthetic. The character of Yitzhak (played by Miriam Shor in both the film and initial theater line-up) was added, Hedwig’s Eastern European husband who loves and hates the prima donna star and hints at a talent stronger than the show’s front (wo)man. The fact that Shor is a woman playing a grungy, bearded man not only gives the songs she backs a tentative off balance shift in octave to Hedwig’s mannered huskiness, but it helps keep the theme of sexuality as a border to be crossed the prevalent theme.

Of course, once the stage show became a hot ticket in New York and went on international tour, the movie wasn’t very far behind the soundtrack, the T-shirt and polystyrene, souvenir blonde perms, and now an all-star indie-rock tribute album. What’s surprising is how much of Hedwig survived the transition and inevitable opening up of the narrative. While the film enhances the importance of Hedwig’s toy-boy lover turned international rock star plagiarist, Tommy Gnosis (another personal John Cameron Mitchell creation played on the big screen by Michael Pitt), to give the film a romantic arc around which to structure Hedwig’s various rises and falls, all the previously mentioned spunk, wit, mirth, and music remain intact. This is obviously thanks in part to the continued active participation of Mitchell, Trask, and Shor in pulling their theater piece out of the motion picture birth canal, but the involvement of production company Killer Films surely was the slap on the arse that made sure “Hedwig the Movie” was a wailing, fluid-covered classic and not a stillborn camp curio. They previously played midwife to transgender critical darling Boys Don’t Cry and failed but high profile glam rock opera Velvet Goldmine.

Although the sing-a-long subtitles during “Wig in a Box” flirt disgracefully with rote audience participation, Hedwig does not want to be the new Rocky Horror. Its live floor show roots ensure that it fulfils all camp requirements outrageously and effortlessly. The “car wash,” in which Mitchell would dangle and rub the hem of his tasseled miniskirt over audience members’ faces, survives here when he performs “Sugar Daddy” to a group of unsuspecting Bilgewater diners—the adaptation constantly reaffirms that Hedwig may be unloved in her own world but has an audience in the cinema who would give their untickled brows to be eating some surf ‘n’ turf in the theme restaurant that houses Hedwig’s rather lackluster tour through her stolen hits and broken but triumphant life. Enthusiasm, energy, and the clever taint of melancholy keep this conceit fluid and epic, many of the musical numbers are performed in the anonymous restaurants with little invention yet they still manage to rock the auditorium wherever Hedwig screens. Floor fillers like “Angry Inch” and “Tear Me Down” could stand alone in their own right outside of this tale of unrequited love, punk performance, and identity shifts. Great tunes are what make a great musical, and Hedwig is the finest, funniest, and most multi-layered of this genre to saunter into the limelight for years.

If Moulin Rouge, with its passionless CGI enhanced dance routines and recycled soundtrack, is the benchmark of the modern musical, then give me Hedwig any day and twice on Fridays. Sure it cannot match Luhrmann’s “cast of thousands” pound for pound in the ring; most of Hedwig’s showstoppers take place on the same barely redesigned set. Yet Moulin Rouge completely fails in the “camp” aspect it so desperately desires to instill, an aspect that Hedwig has in natural abundance. Despite gaudy recreation of Montmarte and Kylie Minogue cameos, Moulin Rouge, with its heavily marketed wide opening, could never be called an actual cult item, and it doesn’t seem to have attained the queer following it so enthusiastically courts. Hedwig, on the other hand, is slowly building back a reputation through word of mouth, through reviews like this, through late-night screenings that would have been its starting point if wasn’t snapped up on the festival circuit so quickly. Mitchell’s flawed gem does have bundles of cheap camp—any movie that marks its protagonist’s rise by the blondness of it wigs (dishwater dirty for breakdown, peroxide white for blissful romantic nirvana) clearly has innate grasp of that mixture of fabulous and artificial that have given classics of the genre their gay followings. Hedwig’s day may come and she’s bound to make a catty remark about that.