The film series Politics as Spectacle: The Films of Mani Ratnam runs from July 31 to August 2, 2015 at Museum of the Moving Image.

Politics as Spectacle: The Films of Mani Ratnam

By Monty Majeed

Often Westerners will tell me how much they love Indian cinema. They love our songs, the vibrant dance set pieces, the melodrama, the action . . . oh, how colorful Indian films are, they say. Hindi-language films, which in the West are referred to as Bollywood films, and are considered to represent the cinema of India, are in fact nothing but a fraction and a gross underrepresentation of the multitudes that India has to offer. Cinema, it is said, transcends the boundaries of language and culture. But in a country like ours, where films are made in at least eighteen languages, this is far from true. A New Yorker watching a Bengali film and expecting that the Tamilan sitting next to him or her would be able to explain it, should know that they are both in the same boat, equally lost and peering at the subtitles to grasp what’s being said. Yes, there’s a common thread of Indian-ness connecting these films that helps us all relate to them, but even today it is sad that many Indian cinephiles have watched films from European countries, Iran, and other parts of Asia, and remain unaware of many of the brilliant works produced within their own nation.

Considering all this, the three titles to be screened at Museum of the Moving Image’s weekend series, Politics as Spectacle: The Films of Mani Ratnam, become relevant. Though he’s made less than five Hindi films in his thirty-two years of directing, Mani Ratnam and his works are quite popular even outside his region, the southern state of Tamil Nadu. Mani Ratnam was born into a family already in the film business. His father was a distributor and his brothers went on to become producers; Ratnam, a management graduate, took to filmmaking. Having watched films from around the world and read issues of American Cinematographer cover to cover, Ratnam became interested in changing the way stories were told onscreen. Right from his debut, Pallavi Anu Pallavi (1983), he tread an unconventional path. The film told of the relationship between an older, married woman and a younger man, a scenario that, in a conservative society like India’s, would still be spoken about in hushed tones.

It took him three more years to strike gold with yet another unconventional romance, Mouna Ragam (1986). While Indian films at that time were still stuck on young love and mostly set in villages, Ratnam’s story begins, unusually, after its couple is married and was set in New Delhi. Mouna Ragam, which is still considered one of the most romantic films ever made in Tamil, captures the awkwardness of a couple in an arranged marriage. He followed this up with his most acclaimed film to date, Nayagan—inspired by both The Godfather and by the real-life story of Mumbai don Varadarajan Mudaliar—which found a place for itself among Time magazine’s list of All-Time Greatest 100 Movies in 2005.

Drawing inspiration from real-life incidents and people, Ratnam’s films, true to the title of the Museum’s series, are spectacles. They have a cinematic language of their own. Each is marked by visual brilliance, measured writing, subtle performances, and breathtaking musical numbers. In terms of themes, his range is wide. Though he continually returns to the friction and uneasiness inherent in human relationships, Ratnam also takes care to place each of his films in a different milieu, and his diverse subjects include inter-faith marriages, social acceptance of people with disabilities, the Sri Lankan civil war, adoption, youth politics, and gangsters.

But it was Roja (1992), the opening selection in the Museum’s series and Ratnam’s eleventh as a director, which turned out to be his breakout. The first entry in what has been referred to as Ratnam’s “terrorism trilogy,” Roja, with its story of a woman’s struggle to free her husband from the clutches of Kashmiri separatists, struck a chord throughout the country. The film won a national award from the Indian government for its promotion of national integration, but it couldn’t escape the wrath of many academics, including renowned social researcher Tejaswini Niranjana, who wrote a scalding essay accusing Ratnam of portraying Muslims in a bad light and for celebrating its Hindu leading man as a “secular nationalist.” This fueled a larger debate about the religious profiling of characters in Indian popular culture. In a country still struggling to bring in communal harmony among its many religious groups and whose citizens still grapple with multiple identities and affiliations, both Roja and the arguments against it remain relevant.

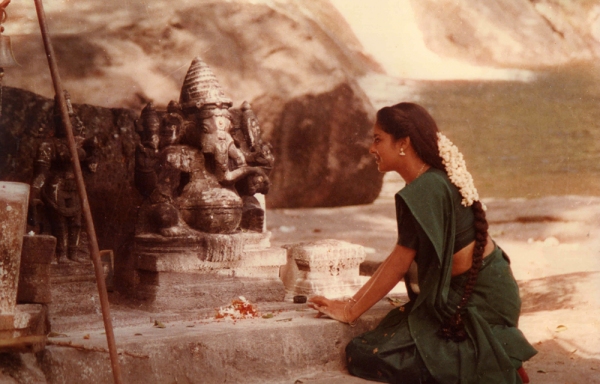

Despite the outcry, Roja is still considered a landmark in the history of Indian cinema. The beginning of a new kind of technically robust class of cinema, the film is important for introducing a number of new technicians to the industry, most notably renowned cinematographer Santhosh Sivan and Oscar-winning musician A. R. Rahman, with whom Ratnam has collaborated on every title since. In most Indian films, songs function as brief breaks from the story, flowing like fantasy or dream sequences, mostly shot in extravagant, beautiful foreign locales. Even though in some cases these musical sequences can eat up more than half of the film’s entire budget, a viewer can skip them while watching the film and it would not change the experience much. But Ratnam is one of those rare directors to use songs to assist the storytelling process. In Roja, every crucial narrative moment is punctuated with a song, and these songs are illustrated with visual inventiveness. When we first meet the cheerful, carefree village girl Roja, Ratnam accompanies her introductory song with a montage of scenes that layer and build her character for the viewer. Songs also show her reluctance to accept her future husband, the cryptologist Rishi, for choosing her over her sister; her relationship blossoming with Rishi, against the giant backdrop of the Himalayas; and, perhaps most movingly, the sorrow and pain felt by Rishi when held captive by the separatists.

Following the success of Roja, Ratnam made two films that tread similar paths in showing the plight of people stuck in larger political or social disruptions. While in Roja he used the Kashmir insurgency, Bombay (1995), the second film showing in the series, took as its subject the 1992 communal riots in Bombay following the horrid demolition of the Babri Masjid. The third film, Dil Se (1998), which was Ratnam’s first foray into Hindi-language filmmaking, is set against the insurgency in Northeast India. All three films follow the same basic trajectory of a couple falling in love and being separated due to reasons they cannot control, and, with the exception of Dil Se, end happily in their reunion. All also provide ample evidence of the realistic yet aestheticized production design Ratnam is known for. The director divulged in an interview that only three days of Bombay’s shoot actually took place in the city of the title; the riots that form most of the film’s second half were recreated down south in the capital city of Chennai. Similarly, in Roja, much of what is passed off as Kashmir was shot in neighboring hill stations or ones in south India.

One of the main criticisms leveled against Ratnam is in regards to class. Bombay’s leading man, Shekhar, is cut from the same cloth as Rishi in Roja: both hail from an upper-caste Hindu family, are educated, modern, and therefore secular (and both are played by the same actor, Arvind Swamy). Most of his leading men are, according to Indian film critic Nandini Ramnath, “attractive, beautifully dressed, and fundamentally decent.” Some claimed that Ratnam, who himself hails from an upper-caste Hindu background, had portrayed Hindu characters as more secular as opposed to the Muslim characters in these films, who come off as more aggressive and rigid. In Roja, Rishi is kidnapped by Muslim separatists when he goes in search of his wife, who is meanwhile praying at a Hindu temple. And in Bombay, which deals with an inter-faith couple trying to make their way in the city only to be caught up in the Hindu-Muslim riots, the Hindu father is shown as more passive and calm, whereas the Muslim father brandishes a weapon at the drop of a hat. Yet it’s important to note that Bombay’s narrative is mostly bent toward nationalism and secularism rather than Hinduism. It’s clear that Ratnam is just being truthful to the stories he wants to tell and to the milieu in which he is personally comfortable.

Furthermore, Roja and Bombay deal intelligently with the reality that India remains divided by language and religion. While a distraught Roja tries to communicate with the Army officers in Kashmir seeking help, she is lost for words, as she knows no language other than her mother tongue, Tamil. And in each film, the leading man saves the day with a long, if a tad simplistic, climactic monologue. In essence, the texts are the same, with a crucial difference: in Roja, Rishi states, “I am not a Tamilan, but an Indian”; in Bombay, Shekhar says, “I am neither a Hindu nor a Muslim, I am an Indian.” An overarching sense of national pride resonates in both films. Probably learning a lesson from the outcry over Roja, Ratnam took care to show both sides in Bombay. In the film, the inter-faith couple stands in for Ratnam’s ideal Indian, one who embraces all religions and cultures; each of their twin boys has both a Hindu and a Muslim name. And when terror strikes, even the warring fathers come together to save each other’s lives.

With Dil Se Ratnam shifts gears, moving away from his picture-perfect endings, pointing toward a more realistic outcome. The film tells the story of Amar’s obsessive love for Meghna, a girl who belongs to an insurgent group and is preparing herself to be a suicide bomber; by focusing more on the characters and on Amar’s obsession, the film avoids making overt messages about patriotism or nationalism. Although it was a huge hit internationally, the film fared badly in India, and many did not take to the depressing climax. Amar, whose father is recalled as an Army martyr, is depicted as driven by love, rather just patriotism, when he tries to stop Meghna from carrying out her mission. And, unlike the other two films, the visualization of songs in Dil Se are more phantasmic in nature. The film depicts various stages of love, starting with attraction, and ends in death. The songs thus stand in stark contrast with the dimly lit, claustrophobic terror sequences in the film, as if hinting that a union between the two leads is nothing more than fantasy.

The brilliant storytelling and technical finesse of these three films—dubbed the “terrorism trilogy”—make them essential, but they are only the tip of the iceberg for Ratnam. Other works equally worthy of your time include his best film, Iruvar (1997), as well as Anjali (1990), Thalapathy (1991), Raavanan (2010, the Tamil version) Alaipayuthey (2000), Kannathil Muthamittal (2002), and Aayitha Ezhuthu (2004). These are stories rooted in his homeland, and which feature Ratnam’s filmmaking at its best. He reinvents himself in every film, experimenting with color, aspect ratios, lighting, camera movements, editing, casting, and music. Ratnam may not be India’s most prolific filmmaker, but he is undeniably a rare breed, walking a tightrope between political and commercial cinema, all the while never failing to keep the viewer engrossed and entertained.

All photos courtesy office of Mani Ratnam.