This Old House

by Jeff Reichert

The Woman in Black

Dir. James Watkins, UK, CBS Films

Of the three children plucked from obscurity to anchor one of the most expensive movie franchises of all time, I doubt many would have placed bets on Daniel Radcliffe as the one who’d make a real go of it as a thespian. Rupert Grint’s goofy, big-faced geniality portended a lifetime of readily available character work (best case: a ginger Ernest Borgnine?), and as Emma Watson aged into icy gorgeousness, one could envision the string of haughty impossible objects and ill-advised, drugged-out-hooker-going-topless-for-the-Spirit-Award outings in her future. Poor Radcliffe, Harry Potter himself, burdened from the start by the heavy weight of being the Chosen One, both on film and in life, always seemed less at ease in front of the camera than his compatriots, every move and line reading the result of very obvious thinking as opposed to reaction and intuition. Though he proclaimed early on that he loved performing too much to give it up, and did a much-publicized nude stint on Broadway in Equus to boost his chops and cred, many could imagine the story ending not unlike his recent Saturday Night Live Hogwarts spoof: Radcliffe, aged beyond adorability, comb-over in place, looking back on the glory days when he was the most famous boy in the world.

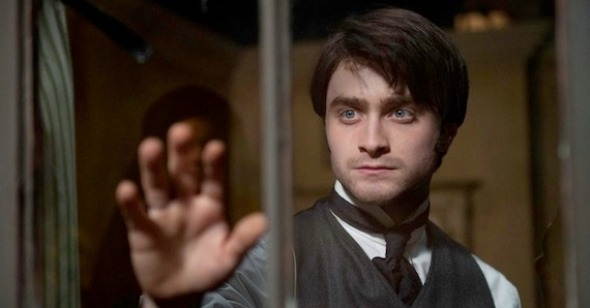

In The Woman in Black, Radcliffe’s first major post-Potter movie role suggests that the cynics among us shouldn’t have counted him out. It seems all that visible straining, which (among other elements) overburdens the early Potter films, was suggestive of not merely a lack of innate aptitude, but a burning desire to hone his craft. Over the course of eight films shot almost back-to-back across a decade, the progression from youngster dazed by the bright lights to wooden teen star to near-credible male lead is apparent; hard work sometimes pays off. Now, freed from the weight of those iconic round glasses, which were the most visible manifestation of the already fully-formed character he was hired to interpret, he jumps on the opportunity to build Edwardian-era estate lawyer Arthur Kipps, still grieving over his wife’s years prior death during childbirth, from the ground up. Radcliffe’s still thinking his way through things, but his Kipps, a single father barely holding onto a low-level law position in foggy London, has plenty of space for introspection. There are several long, dialogue-free sequences of Woman that feature Kipps alone, wandering around this neo-Hammer production’s finely detailed haunted house set searching for the source of strange noises. These bits are often nearly virtuoso in their tension building and, in giving Radcliffe the opportunity to hold the screen without the help of Ron, Hermione, and Voldemort, valuable proving ground for an actor who needed such a chance.

Though his reedy voice at times betrays his age, Radcliffe generally passes with flying colors; in his hands, Kipps is so credibly bereaved that we buy he’s halfway crossed to the other side in pursuit of his dead love, and thus a suitable subject for a good haunting. This is also apropos as the town of Crythin Gifford to which he travels to execute his commission, seems a place made especially for the dead, or those nearly there. Harry Potter’s saga had a built-in sweep and narrative velocity that glossed deficiencies in the child actors, but now Radcliffe has progressed to the point of telegraphing character with a squint of his slate-grey eyes or a twitch of his oddly triangular mouth. It doesn’t hurt that the movie he’s in, though aiming for low-key charms and lo-fi scares, is more immediately immersive than the behemoth productions he’s been mired in up until now. Though The Woman in Black is lean, whatever frills have been stripped from the narrative were clearly reapplied to the richly tactile design of the film. The home of the recently deceased Alice Drablow, a wonderfully named old manse by the name of Eel Marsh (the aerial shot that introduces the isolated island upon which the structure sits is quite breathtaking), is replete with piles of dusty, scrawled-upon parchment, foreboding dark wood doors, half-melted candles, molding wallpaper, a museum’s worth of some of horror’s cinema’s creepiest toys yet seen (and heard—many are set to playing discordant tunes all at once), and, of course, secrets. The main of these being the identity of the titular woman, glimpsed from afar with some regularity once Kipps arrives on the scene.

Attentive viewers might have noticed her outline in the corner of the frame in the film’s unnerving prologue: three beauteous young girls, playing in an attic room, all cease their activities to jump from a nearby window to their deaths. The interrelationship between Kipps’s horrific time spent in Eel Marsh (the house seems to menace him even at the brightest points of the film’s wanly overcast days) and the ongoing deaths of the town’s children is Woman in Black’s other central mystery, and one that could have been plumbed further, if only to offer further space for the great day-work done by the likes of Janet McTeer and Ciarán Hinds who play a husband and unhinged wife whose son drowned years before. Radcliffe is the star here, and deservedly, but the film’s continued insistence on putting him back in Eel Marsh alone does pay diminishing returns, especially when the filmmakers have elsewhere conjured a sequence as disturbing as the one involving a basement fire, a lantern, a young girl locked away for her own protection, and, of course the woman in black.

Even if the film does rely somewhat too heavily on Radcliffe opening doors and lighting candles at the expense of deepening its world for a more free-floating dread, it must be acknowledged that it’s often scary as all get out. Some of this is likely due to contemporary horror cinema’s reliance on sudden volume jumps, but more can be attributed to director James Watkins’s thoughtful framing and source material composed of stuff expressly designed to prey on primal fears. It’s entirely coincidental, but still notable that The Woman in Black is in theaters concurrently with Ben Wheatley’s Kill List, the descendent of a very different strand of British horror. Where that latter film seems to have craftily evolved to soak up modern-day anxieties only to trump them by introducing frights long burnt into the collective unconscious, Woman in Black is traditional through-and-through. Both are valuable in their own ways, especially after an extended period that’s seen little positive innovation in horror or attention to genre basics (save last year’s jumper Insidious, which was pleasingly Poltergeist-faithful to a fault). Choose the new or the old: either way, it’s nice to feel safe to be scared at the movies again.