For God's Sake

by Jeff Reichert

Kingdom of Heaven

Dir. Ridley Scott, U.S., 20th Century Fox

No one does pompous like Ridley Scott. Where a film of average self-importance might look down its nose at an audience from time to time, a Ridley Scott vehicle does so while conducting massed woodwinds and coordinating a rain of individually picked rose petals from the heavens. Sir Ridley comes from a school of filmmaking that doesn’t leave anything to chance because it’s assumed that the masses should be led around by their balls. Ever since the more indefinite Blade Runner he’s steadily ironed out any lingering narrative ambiguity, resulting in a cinema that’s by now almost airtight—that is to say airless. I think the last of his movies to surprise me at all was Hannibal—his Grand-Guignol take managed to flirt with comedy and kitsch in ways that more serial thrillers should consider. I may not like Ridley Scott movies, but somehow I always find myself seeing them. Perhaps it’s because they’re always beautiful and technically flawless, and there’s often something comforting and numbing about staring at perfection. But it’s probably more due to the special place he holds in my heart—it was during his 1492: Conquest of Paradise that a 12 year-old version of myself first realized that movies could be just plain awful.

I’m not sure whether to seriously critique the timing of his latest historical spectacular or applaud it for sheer audacity. Given the gestation period for a project of this magnitude, I can almost see Sir Ridley waking up on September 12, 2001, snapping his fingers—eureka!—with the realization that he had to bring peace and understanding back into the world. The knight would heal the rift between peoples by making a film about a knight healing the rift between peoples! (Or something like that.) Much beard- stroking and the requisite phone call to Akiva Goldsman surely ensued. As Scott doesn’t believe in small strokes, a few years passed while he tossed off inconsequential features like Black Hawk Down, the aforementioned Hannibal, and the oddball Matchstick Men. Through it all, I’m sure the man had his eye on the prize—the moment when he’d find himself in the middle of a desert waiting to be filled with thousands of digital extras. Is a crusade movie produced with monies flowing almost entirely from the coalition of the willing nations what the world really needs right now? Doubtful, but nevertheless, Kingdom of Heaven is here, and most likely playing at a theater near you.

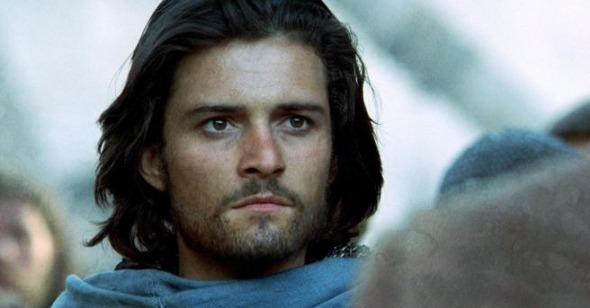

Heaven, though it was almost called “The Crusades,” doesn’t actually focus on all of them, even though you’d think a 145-minute running time might have afforded Sir Ridley a little room to stretch out. Instead, he focuses on a period of relative calm between Christians and Muslims after the disastrous end to the second crusade and before the fall of Jerusalem. Leper King Baldwin IV (Edward Norton in a creepy Eyes Wide Shut face mask) rules over a Jerusalem open to all worshippers and maintains an uneasy peace with his rival, the stoic Saladin (Ghassan Massoud). The relationship between these two leaders is somewhat validated by the history (which is nevertheless distorted and cherry-picked for narrative efficacy) and presents a splendid missed opportunity—apparently the man in the mask wasn’t compelling enough as a hero, so enter Orlando Bloom as French blacksmith Balian, the errant, illegitimate son of Lord Godfrey (Liam Neeson), one of King Baldwin’s vassals. Heaven doesn’t waste its breath, Godfrey’s met and offered his son a spot on his crusade squad within the first five minutes of screen time. “I loved your mother,” he tells him, “not of her own accord, but I didn’t force her. I loved her in my way.” Silly, but it’s enough to convince Balian to kill the village priest in fit of rage, burn his forge, and hit the road for points east. (In another choice bit of wisdom, Sir Godfrey offers: “To get to Jerusalem, go to where they speak Italian, then go until they speak something else.”)

Godfrey is wounded in a skirmish before they’ve even left France (for the curious, that’s seven to eight minutes of screen time before the first blood is shed), and he fades away before making it to Jerusalem. Though the first 15 minutes might seem like a premature point to start throwing in climaxes, Sir Ridley plunges ahead undaunted. Indeed, it’s only moments after Balian bids papa adieu that he finds himself washed ashore in the Middle East after a deadly shipwreck that kills all onboard. The film continues this relentless pace giving the sense that it’s less concerned with telling a story well than with telling a lot of story. I could begin to describe the court intrigue Balian’s immediately thrown into, or the parade of celebrities who turn up for subsidiary roles (Jeremy Irons, Brendan Gleeson, Eva Green), but rest assured it’s probably more vivid in your imagination than it plays out onscreen. Kingdom of Heaven is so hurried that it can’t even find time for the requisite underlit bodice-ripping sex sequence. Balian and Sibylla (the king’s sister, as played by Green) have barely enough time to disrobe and get horizontal before Ridley’s already cut to….a pack of galloping knights? In due course, the King is dead, Saladin’s besieging the city and the untested Balian is left to defend Jerusalem. Though it doesn’t sound like a lot of narrative ground gets covered, believe me—Kingdom of Heaven might make you long for the brooding introspection of Gladiator.

It’s a testament to how poorly Arabs are usually treated in Hollywood film that Kingdom of Heaven has received the blessing of the Arab-American Anti-Discrimination Committee and other like-minded groups, while calls for boycott have rung out in the echo chamber of truly fringe conservative Christianity (if there is such a thing anymore). Saladin’s not a terrorist, seems noble, and his English is attractively accented, so I can definitely see what’s causing the uproar. He wants Jerusalem back but doesn’t desire fighting—he’s the perfect embodiment of the film’s “please everybody” ethos. Nobody’s evil here, except for a few rotten Templars intent on picking a fight. It’d be fair to say that the representations of Arabs in the film are notable only for how instantly forgettable it renders them. I can’t even recall if any besides Saladin and a minor nobleman are even given names. If this is the mark of success in this day and age, I suppose we’ve got to take what we can get.

As with all recent Ridley Scott movies, there’s one tantalizing idea that leads you to believe for a few seconds that there may be more to it than sheer hackery. Gladiator attempted to build a meta-commentary around the politics of spectacle. Black Hawk Down’s glorification of a small company of square-jawed American soldiers ended with the revelation of the massive carnage our “heroes” committed in the course of the film. Matchstick Men, well…. Kingdom of Heaven’s grandest (and perhaps silliest depending on your take) moment comes during its conclusion after Balian and his ragtag group of defenders have fought Saladin’s army to a standstill. Terms of surrender are agreed upon—Saladin gets Jerusalem in exchange for safe passage back to Christian lands for all inside. The invading army enters the city, mingling with the defenders as the camera cranes away. The word “Islam” translates into “surrender” in English, and by glorifying this moment, Sir Ridley’s validated his bland hero, both the Christian and Muslim positions, and re-wrapped history into a package everyone can be happy with. It’s a pretty nifty trick that caps off the balancing act he’d been working the whole film, if you’re buying it. Maybe Ridley Scott’s not so bad after all? Maybe for a second. But then I start to think of how closely the positioning of its narrative hot points matches the construction of, say, a Harry Potter movie and wonder: Given the legacy of the history and the current geopolitical climate, how can 20th Century Fox justify selling people a Crusades epic when all they’ve got is another Ridley Scott movie?