Solar Power

by Andrew Tracy

The Sun

Alexander Sokurov, Russia, Lorber Films

Hou Hsiao-hsien’s City of Sadness opens with Emperor Hirohito’s radio announcement renouncing his divinity going unremarked by a Taiwanese family as they gather around a newborn son, establishing both the distance of power from the everyday and its invisible pervasiveness. Hou’s tactic is not simply a clever way of handling a tale of people caught up in the world historic, a clichéd notion which simultaneously aggrandizes the individual’s tragedy while subordinating him to the seeming untouchability of historic forces. The oblique scenes in which Hou depicts Taiwan’s White Terror are truths in themselves, not cryptograms to be decoded for the historical answers they contain, not mere indicators of something beyond the limits of the frame.

It is one of our more damaging and persistent fictions that identifies power with truth—as opposed to honesty, which almost no one would accept—because it spawns the further fiction that those who hold the former possess the keys to the latter. One hardly needs Marx to detect the fallacy behind the notorious words that a Bush White House aide spoke to reporter Ron Suskind in 2004: “We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality. . . we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.” Risible and terrifying at the same time. Deposing the placeholders of power, whether by force, exposure, or ridicule, does not liberate truth any more than it ends the future exercise of power. This does not lift responsibility from the placeholders; it only exemplifies the fact that it is impossible to create a master narrative of our times from the exploits, and ravages, of the powerful. If they serve our understanding at all, it is as momentary nexuses through which various realities—those created by them and those of which they cannot even conceive—momentarily intersect, assume the ghost of a definite form before resuming their serpentine courses through our past and future history.

If I had to guess—and guessing is the best I can do—I’d choose this as the guiding principle of Alexander Sokurov’s version of Time-Life’s Great Figures of the 20th Century, one of the more bewildering projects from one of the most eccentric filmmakers now working. Perhaps the pliant sensuality of the -and Sons (Mother and Father) or the surefire gimmick of that art-house crossover Russian Ark have managed to disguise just how peculiar the man is: the demeanor (and the moustache) of Tarkovsky at his most messianic coupled with an aesthetic that strays far closer to the absurd than we usually allow of our Serious Artists. (Anybody remember the hero’s wrestling match with the corpse and the grumpy mortician in Second Circle?)

Moloch, that gay romp with Adolf and Eva at Berteschgarten, employed bizarre theatricality without the comforting (yes, comforting!) Brechtian devices we might expect. Representation and recreation are clearly not Sokurov’s concern, as they were in the impressively mounted but negligible Downfall. Slow and lethargic, Moloch nevertheless keeps us perpetually off-balance, the complex interplay between voyeur and viewed, the inescapable conspicuousness of power rather than its cunning concealment, moving us away from the psychology of power to its ontology—and besides that, it’s probably the only film where you’ll see Der Führer taking a dump in the snow.

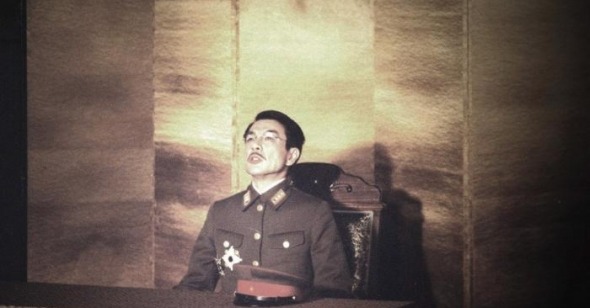

Not having seen the Lenin film, Taurus, I can’t comment on the entirety of Sokurov’s project, but the most immediately noticeable quality of his film on Hirohito, The Sun, is the kind of surface verism, sketchy though it is, which he usually disregards. Covering the last few days after the fall of Japan and before the historic radio announcement, the film, like its predecessors, traverses very little physical ground (the need to keep power secluded from the world in which it is exercised is a recurring, darkly comic motif): the bunkers of the imperial retreat and the gilded splendor in which the conquering Americans and their resident king, MacArthur, receive the former deity-in-the-flesh. Upon this sparse spatial canvas, Sokurov inscribes the nuances, mannerisms, and peculiarities of this strange little man reluctantly bearing the mantle of godhood: his exasperation at having to go through a chain of servants in order to have the radio turned on; his slightly befuddled, halting experience with a door handle, the first he has ever had to open himself; living up to his resemblance to Chaplin by comically slapping his hovering valet on the forehead; his awkward reunion with his wife (how exactly does one kiss a god?) and struggles with her hat and veil.

Sokurov’s emphasis on the physiological is too strange to be reducible to a mere degradation of the powerful. Nor can he really be accused, as Stefan Steinberg does on the World Socialist Web Site, of vaunting his rather taxing formal exactness over the freighted historical and political content with which he deals. I doubt that Sokurov would undertake such a project simply to show the “human being” behind the figurehead of power, as he has stated. Sokurov’s comments, scornfully quoted by Steinberg, are hardly a means of understanding the films themselves. In this, Sokurov simply joins the long line of filmmakers whose proclamations on their own art are often diametrically opposed to how the artwork itself functions.

If Sokurov actually believed that a greater truth lay within the individual shorn of social, historical, and political context, he would never have made his Hitler such a pallid, masked grotesque, nor had his Hirohito (well-played by Issey Ogata, fondly remembered as Mr. Ota in Edward Yang’s Yi Yi) incessantly move his lips to emulate the fish upon which the amateur ichthyologist waxes passionately to mostly unheeding ears. Sokurov is not seeking to humanize these beings made “inhuman” when they “acquire this terrible weapon—politics”; as Susan Sontag noted in her essay on Riefenstahl, the plain evidence of Hitler’s all-too-human foibles in Triumph of the Will (his awkwardness, unimpressiveness, even clumsiness) only accentuated his mythic image.

The baseness and comprehensibility of the human is inseparable from the often inhuman exercise of power, and it is the paradoxical, profoundly incomprehensible polarity of this truth which Sokurov’s deeply strange (I say it again) films address. To mock and degrade the myth of power, particularly when it is localized in a single, fault-ridden human body, is an easy task; what’s difficult is to locate the actual power which circulates autonomously of that body. Sokurov’s triad of dictators—one in full possession of power, one watching it slip away along with his failing breath, one happily renouncing it—actors in linked but markedly distinct social and historical contexts, are similar only to the extent that they cannot, now or ever, grasp the nature of the forces they have set in motion. In the final, disarmingly quiet scene of The Sun, the emperor is informed that the young sound technician who recorded his speech of renunciation has committed hara-kiri. The myth exceeds the body which activates it: The power which Hirohito signified pulsates through a million other bodies even after he has foregone it, fires and shapes a million other minds each in their own singularity even as it unites them in common purpose. Power is always elsewhere, and it is the ironic marker of the powerful that their immediate environments are voided, emptied of the forces they represent and employ.

I wouldn’t want to hold Sokurov to any of these conjectures, however. Despite its relative accessibility, The Sun is too standoffishly insular to yield any grand readings. The political implications of Sokurov’s cinema hover inscrutably within the bizarrely mannered opacity of his style; if Hou sought out the world’s other truths, Sokurov refracts the world historic’s lies within a skewed crystal. It’s a definite provocation to deal with the monumental on a strictly formal level. To charge Sokurov with aestheticization is a moot point, for power’s aesthetics—not its functions or effects—are all he’s interested in. An apt comparison might be Miklós Jancsó, whose dreamlike meditations on the fluctuations of power increasingly subordinated politics to the hermetic language of his camera. Does history freed of historical burdens by the imposition of form whitewash the terrors it encompassed? Is judgment, implicit or explicit, a necessity when dealing with these avatars of power? Sokurov is mute on this point, mute towards anything outside of his own private design. If understanding is not his goal, it remains an open question whether the strange, mysteriously tactile reality he has created can stand alongside those terrible realities we know all too well.