Unspoken Truths

Michael Koresky on I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone

Tsai Ming-liang nearly hypnotizes the viewer with his elegantly composed static images and methodical pacing, but rarely has a filmmaker encouraged such active engagement with stillness. The Taiwanese director might be the visual narrative stylist par excellence working in cinema today; an entire story, a life, a world breathes through each shot of his films, even as he rarely burdens them with spoken language. Often, it will take a moment for your senses to adjust to a new Tsai composition—at once teeming with life and emptied out, this place will force your eyes to wander and scan the frame for signs of movement, color, or familiarity. Tsai gives us time to surmise, to interpret, and distill his motives, to watch how sunlight changes as it beams through a window or to scan all corners to see from which end people will emerge. Such demand is not only respectful of its audience but it also invigorates them—Tsai's films leave one’s eyes wide with wonder and expectation.

His latest film, the heartrending I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone shies away from dialogue at least as much as his glorious 2003 paean to the dying palaces of moviegoing, Goodbye, Dragon Inn. Aside from some brief introductory scenes of a garrulous con man trying to swindle Chinese immigrant Hsiao-kang (Tsai's muse Lee Kang-sheng) out of money before leaving him a bloody, bedraggled mess on the streets of Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur, I Don't Want to Sleep Alone treads delicately and wordlessly across its terrain. With its portrait of immigrant workers living in impoverished conditions, the film uses a new setting for its director's expected but always surprising minimalist tactics.

There may not be much radically new in Tsai's approach to camerawork and storytelling, yet the film's distinct naturalism feels worlds away from his previous, almost metaphysical stylization. Perhaps it's because he's back home: after years of working in Taiwan, Tsai has returned to his native Malaysia, and though it offers a sense of dislocation, there's also a revitalized sense of social awareness.

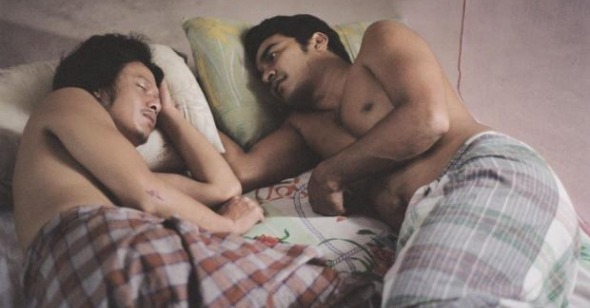

A remarkable addition to the Tsai repertoire is Norman Atun as Rawang, the Bangladeshi construction worker who takes the bruised Hsiao-kang into his bed (actually a ratty old mattress he and his coworkers found on the street and lugged back to their hollowed out, unfinished factory home). Though their union is more about healing than sex, scenes of Rawang tending to Hsiao-kang's body and soul make for some of the most erotic moments in Tsai's oeuvre. Never one to leave sex uncomplicated by psychological and environmental blockages, Tsai parallels this with the physical and emotional frustrations of waitress Chyi (Shiang-chyi Chen), who's tending to a paralyzed young man (also Lee Kang-sheng) while developing a longing for Hsiao-kang. Tsai brings his three principals closer to a direct emotional understanding than he ever has before with his characters—even amidst the threat of death, which is embodied by a thick smoke that descends upon the city.

Moving to the no-man's-land of Kuala Lumpur from the more familiar cityscapes of Taipei, Tsai has even found a more direct motivation for his preference to tell stories through images rather than dialogue: the great language divide of his main characters. So Tsai lets the formations and expressions of faces and bodies take center stage. One moment, impossible to shake for its tender, sexy pragmatism, occurs when Rawang must help Hsiao-kang urinate. Arms around each other for balance, the men stand by an open window, their skin shimmering with hazy afternoon light in a luminescent image conveying empathic mutual support. Tsai has created a wondrous reverie of humanity in bloom amidst the squalor of everyday living.