Disclosure and Pursuing the Trans Film Image

by Caden Mark Gardner

There is a difference between making a film of sociopolitical and cultural value and making a film about important sociopolitical and cultural matters. In some cases the latter may beget the former, but it is not a given. Sam Feder’s new documentary Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen, unfortunately, is a film on an important topic, but it’s scattered, unrefined, and incoherent in execution. While announcing itself as a definitive look at the histories of trans lives in film and television, the film is at best incomplete, an exploration that rarely engages beyond the most surface-level discussions about trans representation. The film lacks the narrative through line of both trans history and any in-depth analysis of the trans image onscreen. For a film claiming to be about trans film history, Disclosure omits a wealth of notable trans-centered films, filmmakers, and performers; however, based on how most of the films are discussed in the documentary, there is reason to doubt that their inclusion would have been fruitful or satisfactory. The film presents the trans film image strictly in terms of visibility, rather than sorting through the aesthetics and politics of how the trans film image has been represented on-screen throughout film history.

Aesthetics, down to the basics in how a film is cut, how a character is lit, how a camera is angled toward the trans character—how a trans body is presented through the eyes of a non-trans filmmaker—have been heavily weaponized against trans people. Often, they have been represented as villainous, unstable, lecherous outcasts, or just plain subhuman abnormalities. Even the most well-intentioned films about transness are not immune to this, unconsciously falling into the patterned, deeply ingrained behavior of filming trans bodies with an unmistakably clinical or even leering gaze. Disclosure seems uneasy with probing some of the more egregious instances of aesthetics used against the trans body; only one talking head in the doc, the great trans scholar Susan Stryker, explicitly discusses these issues in a critical way.

Feder’s film is more preoccupied with trans representation within mass-market entertainment. This feels insufficient, because it must be remembered that, even as the real world has evolved, trans viewers and artists have not waited idly by for media companies to throw them crumbs of positive representation. It would be more beneficial for these viewers and artists to pursue the legacy of trans film image-making, mining film history, perhaps finding work worthy to be reclaimed or reconsidered. Legacies are essential, and we should know how media representations are in dialogue with the international cinematic history of transness. If filmmakers are privy to that dialogue, they can create a truer trans film image, informed by their own lived-in experiences and stories. Disclosure might leave viewers wondering about other films that have represented trans lives throughout history: the titles discussed below are just a starting point.

It is true that the trans image on film has been historically and predominantly compromised. After Christine Jorgensen’s sexual-reassignment surgery in 1952 made international headlines—The New York Daily News said on its cover, “Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty”—and rewrote the possibilities for countless people, several books and films were made in reaction, not explicit adaptations of Jorgensen’s own story (although her memoir was later adapted into a film in 1970) but works inspired by the phenomenon of sexual reassignment. Most of these were low-budget B-movies and exploitation films, portrayals amounting to just “man in a dress” narratives, ranging from Ed Wood to William Castle, still largely seen as more crude than artistically engaging. In Disclosure some, but not all, of these films are briefly shown in montage with no deeper commentary. Yet there were many pre-Stonewall films that tapped into the subcultures of cross-dressers and trans people who were medically and socially transitioning. Some of these works were educational, sideshow, or infotainment nonfiction, like Queens at Heart (available as an extra in Kino Lorber’s restoration of Frank Simon’s documentary The Queen) or the Nikolai Ursin short Behind Every Good Man. These films are an outsider’s look, featuring their subjects directly addressing how they see themselves in the world, with a “walk a mile in her shoes” kind of perspective.

Throughout the sixties, underground cinema presented trans women and cross-dressing as some of the ultimate markers of transgression—from Paul Morrissey’s films in the U.S. to Toshio Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses in Japan. Matsumoto’s film is a gender variation on Oedipus Rex, a nonlinear assemblage of slapstick comedy, comic-strip text boxes, and psychedelia that recalls Kenneth Anger and Jonas Mekas, and features fourth-wall-breaking documentary testimonials of Japanese “gay boys,” who live as women and discuss their characters onscreen and whether or not their lives as represented match their own. The film is audacious especially for its time, and has proven accessible to many viewers who later discovered the film. New York trans activist and editor of the trans quarterly DRAG, Bebe Scarpinato (also known as Bebe Scarpie), wrote of Funeral Parade of Roses in 1973, “What remains uncanny although the setting is in a different culture, [is that] some scenes easily could have taken place in a New York bar.”

Despite the activism of Post-Stonewall gay liberation, trans people often felt like they were getting the short shrift despite marching and participating in the movement. Tensions in gay and trans coexistences are brought to the fore in 1971’s Some of My Best Friends Are… Directed by Mervyn Nelson, this film, set during Christmastime at the Blue Jay, a gay bar in Greenwich Village, is noteworthy for who is playing the trans woman. Candy Darling is forever known as a Warhol Superstar, but in the films Warhol produced with Paul Morrissey, she was always playing a cis woman, not a trans role; along with Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn, such casting was seen as having ulterior motives in mocking cis femininity and radical feminism. Darling’s character here, named Karen, is demure, opposed to the assured glamor of her Warhol/Morrissey roles. She makes small talk with men but is guarded, highly cognizant of how she is seen and what surrounds her. This film is an ensemble piece, but Darling’s Karen is granted more rigorous attention than anyone else. Her aspiration of having her femininity embraced through the love of a man is manifest in a dream dance sequence: her brown wig becomes blonde; she’s wearing a beautiful, red dress; and her voiceover goes into daydreams of ecstasy. However, the pendulum swings back into a hard, brutal reality when Karen is confronted by bar patrons who don’t believe she belongs. This results in a long, painful scene where Karen is beat up and her wig is removed, her natural, shorter hair revealed. It is a shocking moment, but there’s a metatextual aspect: Darling, giving so much for this small movie, had never appeared without a wig as a performer. She abruptly leaves the bar to no fanfare, after being dead-named by even the bar patrons who defended her. The film continues without her. This type of scene would today be a common trope of onscreen trans violence, but there is something particularly disquieting in how it’s shown here: how a subculture of outsiders can themselves be non-inclusive. Sometimes showing a truthful trans image is painful but necessary in acknowledging an existence that for too long has been associated with violence, ignorance, and exclusion.

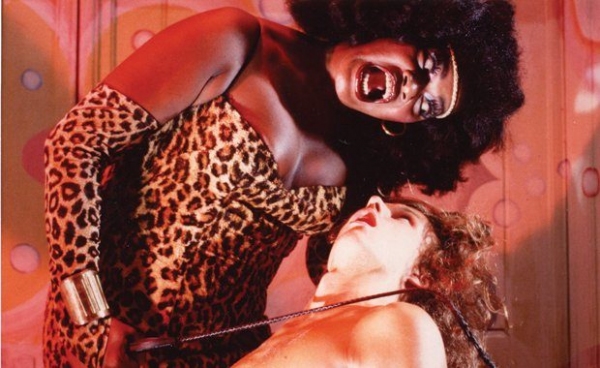

Images of trans-inclusive spaces have existed for decades in pageant culture, cabarets, and ballrooms. German director Rosa von Praunheim’s City of Lost Souls (1983) follows two American expats, trans punk singer Jayne County and black trans performer Angie Stardust (who was thrown out of the American drag circuit for taking hormones) as they try to carve out life in West Berlin in the greasy spoon Hamburger Queen. It is a hybrid of musical performance, fictionalized tableaux, candid testimonials from Stardust on coming to terms with her gender identity, and pointed Reagan era sociopolitical commentary. It is not a fantasy “island of misfit toys” scenario, but a dialectical exploration. The Berlin Wall appears in one scene and County sings of her love of Karl Marx in another. Praunheim has for decades dedicated a film career to covering the full spectrum of LGBTQ culture (he would also make a documentary on the American trans political action group Transsexual Menace, criminally unavailable), and with his high-concept combinations of satire, punk, cabaret, Western kitsch, Marxism, and outsider art, City of Lost Souls feels foundational for John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch, the broader, more consumable version of a gender variant image. City of Lost Souls ends in a utopian euphoria as the ensemble sings County’s penned title track at the Hamburger Queen’s storefront with German onlookers greeting the performers with wide smiles and wonder.

The trans image in the age of television and the daytime talk show gave rise to a high volume of transness as spectacle, revelation, and occasional confrontation. In Robert Altman’s Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean, a glamorous wealthy woman with big red hair by the name of Joanne (Karen Black) reveals to a group of women that she is a trans woman and a former member of their small Texas town’s fan club, the “Disciples of James Dean.” Kathy Bates’s Stella Mae exclaims, “I’ve seen things like you on TV!” When pressed about what to tell other people about her transition, Joanne curtly responds, “Just tell them I’m a freak. They know what that is.” The film, and play on which it is based, flows in and out of past and present, with Joanne’s identity prior to transition, Joe (played by Mark Patton), appearing in flashbacks twenty years earlier. What starts as a contrast of a male and female identity begins to coalesce as one identity. Ed Graczyk’s script can trip over itself at points, but Joanne holds firm in her femininity and womanhood even when facing personal rejection. The film shows that Joanne’s reckoning of her past can never be removed from her life story, and her acknowledgement of that is reflected in the way Altman composed the set, of two identical spaces, separated by mirrors, with the characters in the past and present played by the same actors—save Black and Patton. The mirror image concept turns out not to be a trap for the trans image, but a breakthrough. Similar to how trans women function in a matriarchy alongside cis women in Pedro Almodóvar films, Joanne is able to sing and dance along with Cher and Sandy Dennis to The McGuire Sisters’ “Sincerely,” and she is finally referred to as “Miss” by her biggest adversary, the bigoted religious zealot Mona: an earned victory.

Trans masculinity remains underexplored as a subject. That Boys Don’t Cry is still in 2020 centered as a sort of urtext to trans masculine images is, to put it bluntly, ridiculous. Boys Don’t Cry was seen as a sun-setting film for New Queer Cinema, when the movement had officially graduated from being at the center of censorship and art grant controversies to winning Academy Awards. Two trans men who tried out for the Brandon Teena role that won Hilary Swank an Oscar, Harry Dodge and Silas Howard, made the buddy crime movie By Hook or By Crook (2001). The film is barely known in mainstream culture, despite the fact it was made by and starred two still active trans male artists. The film—in which two trans men find each other by chance in the middle of nowhere and become partners in crime—feels like a long exhalation, with Howard and Dodge’s characters both remarking that they had never before been able to talk to anyone who shared their experiences. The film portrays trans men affectionately as gender outlaws, much like earlier New Queer cinema films portrayed gay and lesbian characters as sexual outlaws. By Hook or By Crook functions on its own as a portrayal of trans masculine brotherhood, but it also functions in contrast and critique in the way that Dodge and Howard film their own bodies versus how cis directors shoot trans bodies. There are no intrusive, probing shots of their differences or presentation. These characters already know who they are even when much of the outside world did not.

Documentation of transness in adolescence has manifested in reality television and YouTube self-documentation, but had already existed in experimental cinema. Sadie Benning’s 1998 film Flat Is Beautiful is a bildungsroman and thinly veiled memoir of the filmmaker’s gender questioning and trans non-binary identity that they would later disclose. The film’s lead character, Taylor—a most gender-neutral name—adorns a paper mask, grapples with their gender identity. They love Madonna and the Milwaukee Brewers in equal measure, and in a world of gender difference, Taylor finds themself fluidly exploring the in-between of the binary, seeking to carve out an identity of their own creation that preexists a term or category apparent to them. Like many of their experimental shorts, Benning shot Flat Is Beautiful with a Fisher-Price PXL 2000, a toy camera that creates a pixelated, black-and-white image. Using “pixelvision,” marketed and intended for young children, to tell Taylor’s story predicts how the next generations of queer, trans, and non-binary youths would search, question, and use the Internet and video diaries to claim their own authorship.

The proclivity to use the trans film image as a signifier of social progress has been predominantly seen in documentary nonfiction. Frederick Wiseman’s 2015 In Jackson Heights is largely spoken about for how it focuses on multiculturalism as a melting pot threatened by gentrification. But hidden within that film is a nuanced representation of the differences between cis gay and trans lives. Wiseman shows how during a time of LGBTQ Pride, white cis gay men can be visible and present their identity in parades, while trans women of color are shown decrying harassment from local police forces. Wiseman also presents scenes in which trans people grapple with their everyday realities in group therapy sessions. Documenting this side of the trans image, people who vary in age and race but share a similar socioeconomic class, shows a perceptive understanding of the trans experience. Contrast that with Wiseman’s earlier Hospital (1970), which features an especially upsetting scene in which a black cross-dresser—who appears to be under tons of sedatives—coolly states that they are “not a normal human being” and openly opines of identifying as a woman, while a doctor diagnoses them as a schizophrenic and unsuccessfully attempts to prevent the patient from getting placed in a mental ward. Times have changed in how the trans image is discerned and perceived, but the trans image is still heavily ensnared in several political debates that center their livelihood.

In our current sociopolitical moment, transness is often tied to debates about sex work, homelessness, policing, and incarceration, and these issues disproportionately affect trans women of color. Sean Baker’s 2015 film Tangerine presents a day in the life of two trans sex workers of color. The absence of discussion about Tangerine in Disclosure, despite its wordless ending being briefly shown, remains perhaps one of the most inexplicable of Feder’s choices. Is this exclusion a matter of respectability politics? The film is about Sin-Dee (Kitana Kiki Rodriguez), just out of prison, who explodes when learning that her boyfriend is dating a cis woman and the chaos that unravels from her wrath on Christmas Day. Mya Taylor (as Sin-Dee’s best friend, Alexandra, the first trans woman who won an Independent Spirit Award for Best Support Supporting Female) and Rodriguez provided a contrast to a Hollywood that continues to push cis male actors playing trans women as costume (perhaps none as shamelessly as Eddie Redmayne’s absolutely wretched performance in The Danish Girl as Lili Elbe, the first sexual-reassignment surgery patient, who becomes a ham-fisted martyr through Tom Hooper’s misguided direction). Tangerine is a kinetic shot in the arm. Here, the trans image jumped from celluloid to digital to an iPhone 5s; these bodies are in constant motion, trans women doing the best they can to survive in their day-to-day lives. Even if their images cannot entirely approximate the entire trans experience, several truths lie in Taylor and Rodriguez’s performances.

Discussions about the trans image onscreen cannot just be reduced to the task of avoiding harmful or stereotypical representation. But Disclosure seems content to stay in that terrain. The film barely presents a historical or critical framework even as it asserts itself to be a thorough investigation. There’s a lack of imagination in a film that expects a trans viewer might prefer to tread only in the territory of commercial, contemporary films that feature recognizable faces. The trans image can be found in so many places and, despite everything trans people have been led to believe, this includes an entire history of cinema.

Reverse Shot is a publication of Museum of the Moving Image. Join us at the Museum for our weekly virtual Reverse Shot Happy Hour, every Friday at 5:00 p.m.

![]()