Small Pleasures

By Nick Pinkerton

Notes on an Appearance

Dir. Ricky D’Ambrose, U.S., Grasshopper Film

Notes on an Appearance is a small, curiously enticing movie with the aspect of a game about it, a deceptively simple looking game with only a few moving pieces, though you’ll have to muddle through without the instruction book. It is a playful thing, rattling with little bibelots, and this is for the good, for we could use more games amid the self-serious heft of so much contemporary cinema. As it proceeds, though, it cultivates a mounting feeling of unease—for who in these troubled times can be bothered with games?

The movie begins as a young man, David, returns to the New York City area after a stint in Milan, staying with an American girl, Madeleine. After an unhappy homecoming to his parents in Chappaqua, Long Island, who begrudgingly send him on his way with a check, David hooks up with an old college friend, Todd, who is working on a biography of an American political theorist named Stephen Taubes, aiming at the “intellectual rehabilitation” of the controversial figure. Todd brings David on as a research assistant, itemizing the contents of a box of videotapes left behind by Taubes, documenting his travels during the last two decades of his life—these, presumably, are the source of the commercial camcorder-quality interstices shuffled into the film. David, who appears to be somewhat aimless and unclear about his future plans, periodically narrates approximately the first quarter of the hour-long movie, but then he disappears, last seen desultorily walking a street in downtown Brooklyn. From this point the focus of the narrative shifts to Todd who, joining forces with a newly arrived Madeleine, tries to discover anything that he can about his missing friend, launching a meandering investigation. His search for answers continues even after a body fitting David’s description appears on the beach at Jacob Riis Park.

Notes on an Appearance takes place in a rarified Brooklyn milieu, consisting mostly of twenty- and thirty-somethings who went to Bard or Cooper or Sarah Lawrence and contribute to n + 1 and have friends in group shows and casually say things like “I was in Senegal for five weeks.” This is a small and involuted sect, and his cast is drawn from a similarly shallow pool, that of New York independent film and cinephilia. The actors playing Todd and Madeleine, Keith Poulson and Tallie Medel, will be familiar to a viewer with a working knowledge of microbudget NYC movies—Poulson has appeared in a string of films, often as an affable but clueless dude with whom the leading lady falls into bed when her first pick is unavailable; Medel has worked steadily since her breakthrough in The Unspeakable Act (2012) by Dan Sallitt, who also appears briefly. David is played by Bingham Bryant, co-director of the 2014 film For the Plasma. James N. Kienitz Wilkins, maybe the most sheerly inventive of the current crop of no-budget filmmakers, plays Madeleine’s one-night-stand, whose idea of foreplay is leafing through a book of century-old pictures of Romanian peasantry. The eagle-eyed can even catch film critic cameos from Glenn Kenny and n + 1’s own A.S. Hamrah. You might accuse writer-director Ricky D’Ambrose of buttering up the niche audience he is addressing—two Film Society of Lincoln Center programmers even appear onscreen, one with a brief speaking role, and Bryant works as a publicist—but at the same time there is something perfect in this casting for a movie that represents the rapid circulation of conspiratorial groupthink among a hermetic, circle-jerk group. As it is, I am perhaps uniquely qualified to discuss Notes on an Appearance, as I am one of the only people in New York film culture who isn’t in it.

The cast, reflecting various degrees of acting experience, are put on approximately the same level through the imposition of a blank, affectless delivery, which for lack of a better word we will call Bressonian. This creates a mood of the uncanny; it is also purely practical—John Waters wrote years ago of Bresson’s Lancelot du lac (1974) that “students of film budgets ought to watch this great screen economy at work,” and he has become a lodestar for impoverished productions. Speaking generally, D’Ambrose’s movie fits with a contemporary—but by no means unprecedented—minimalist, microbudget school, in which filmmakers draw their material from their immediate surroundings. This is an art cinema that embraces the marginal position of the concept of art cinema today, and as such lends itself to a certain involuted or incestuous quality—see the preponderance of filmmaker Q&A scenes in the films of Hong Sang-soo, echoed here in an “open it up to the audience” moment following a panel on translation. Of the current New York School, D’Ambrose’s approach reminds me not a little of the Matías Piñeiro of Hermia & Helena (2016): D’Ambrose is unusually reliant on insert shots to advance—or waylay—his narrative, beginning with the postcard of the Duomo with which David announces his imminent arrival in New York, and continuing through a steady accumulation of ephemera, the “Notes” of the title.

D’Ambrose takes an evident pleasure in printed matter, and this is the medium through which the film’s other physically absent major character, Stephen Taubes, appears to us. Taubes is a fictional creation, but D’Ambrose has created a very convincing paper trail for him, giving full-frame close-ups to font-perfect articles from publications like the New York Times, NY Review of Books, Harper’s, and The New Yorker, signed to very real authors like William Grimes, Peter E. Gordon, Christopher Beha, and Louis Menand. If you read quickly, you can pick up certain facts about Taubes: he died in 2013 at the age of 67; was a Sterling Professor of the Humanities at Yale University; wrote a series of books with titles like Flight from Capital, Regress/Redress/Progress, Violence and Its Valences, and Everything Is Permitted: History at the Abyss; and at the end of his life had become a sort of cult figure on the basis of the appeal of his rallying against liberal democracy. He is no stranger to controversy, having been discovered to have contributed articles to a far-right Vienna newspaper in the early 1980s, and tangled up in the unsolved murder of a journalistic critic in 2011. The Gordon piece, for example, repurposes something by the author on Martin Heidegger’s “black notebooks” of the years 1931-41, covering the period of the philosopher’s commitment to National Socialism, while another piece cribs passages from a book on Paul de Man, the Belgian-born deconstructionist literary theorist whose reputation was blackened by the posthumous revelation that he’d contributed to collaborationist and anti-Semitic publications in his youth, at the time of his death, yes, a Sterling Professor of the Humanities at Yale.

Taubes’s philosophy, inasmuch as anything can be understood of it, is of a messianic, accelerationist kind. His cited influences are the militant French Catholic Joseph de Maistre and the Russian revolutionary nihilist Sergey Nechayev, whose disruptive, charismatic presence was part of the challenge that Dostoevsky sought to meet with his Demons. D’Ambrose’s other points of reference are mostly onetime fascist sympathizers—Heidegger, de Man, and Wyndham Lewis, a copy of whose Tarr David leaves behind with his research papers—though his work is published by Verso Books, generally affiliated with the radical left. A gruff, phlegmy voice, presumably belonging to the high-handed firebrand philosopher, is heard towards the end of the movie, basking in applause for questioning the “sanctity of human life” while promising his audience that soon “this entire sickly order is going to implode.” In the world of Notes on an Appearance, these sentiments have struck a nerve, and the movie depicts an outwardly placid bespoke Brooklyn in which anarchist, anti-humane sentiment is common intellectual coin. Even dead and buried, Taubes, like Dostoevsky’s Nechayev-inspired Pyotr Verkhovensky, has the ability to transmit his doctrine of revolutionist ardor like a pestilence, and it travels rapidly through a trend-sensitive New York, where everyone who was snapping up Roberto Bolaño novels ten years ago now is planning the violent overthrow of the established order. Todd seems to belong to a pro-Taubes faction of some kind, and his continuing preoccupation with the case of his missing friend is considered an anomaly among his cohort, above such petty, individual concerns. “It’s a distraction,” an academic friend (Madeleine James) upbraids him, “and as far as I’m concerned it’s something that never even happened.”

D’Ambrose’s movie, so deceptively light, is in fact a packed dossier, loaded with information and pieces of physical evidence that, by virtue of being singled out in those recurring inserts, appear to take on a heightened relevance to the case at hand. (The very physicality of this evidence marks Notes on an Appearance as a throwback in the digital era; as a counterpoint I would recommend Eugene Kotlyarenko's 2010 Instructional Video #4: Preparation for Mission, aka SkyDiver, a still-unmatched farce of Internet era radicalization.) There are plane tickets and correspondences and business cards and blueprints and loads of cartography, including subway maps to denote changes of scene and wall didactics at a gallery opening which display an excellent mimicry of pompous gallery style: “Grandiloquent but semantically silent,” “Color and materiality evoke an embodied visual experience,” and “Use of grids and patterns creates an illusion of order; However, this is a decoy… playful dis-logic charms the viewer’s eye in an absurd and cyclical non-narrative.”

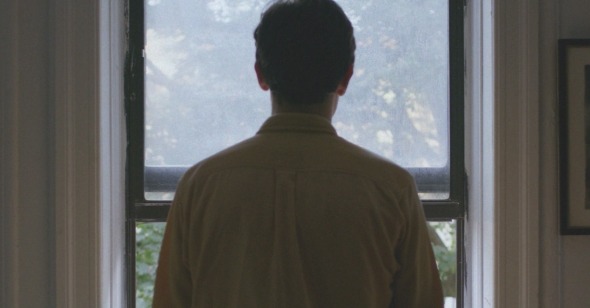

That last bit feels like a plant, a self-description of D’Ambrose’s own feint—though dealing in obscure conspiracy, Notes on an Appearance has a uniformly orderly, fussed-over appearance. It takes place mostly in brightly lit rooms, in a procession of sanguine setups presenting evidence with almost clinical clarity, often against a blanched backdrop; bright colors when they appear are restricted to monolithic slabs—David’s yellow shirt, the red walls of the room where Todd and Madeleine cross-examine his cousin, or those occasional blocks of neon green that fill the screen.

Is any of the material placed before us relevant to David’s disappearance? Is it coincidental that Todd’s roommate and friends, at the end of the film, head out to the same beach where David’s body was discovered, 15 feet from an embankment at the southern end of Beach 149th Street? What does Todd’s roommate mean when he says of the trip, “This may be our last chance to do it”? Is he anticipating the end of the summer, or the end of the social order in general? Was David a victim of a conspiracy among Taubes acolytes, slaughtered and disposed of like Nechayev’s disciple Ivan Ivanov? Might the blacked-out passages of a text in his shorthand provide the answers? Do those neon green screens represent excised material? Did David see something he wasn’t supposed to see while parsing through those Taubes home videos?

Of the videocassettes that he is itemizing, David notes, “Their importance was unclear”—a statement that applies to the parade of miscellany in Notes on an Appearance. D’Ambrose’s intention, if I read it right, is to induce in the viewer a heightened state of anxious vigilance, pelting us with bits of intelligence of uncertain application. The movie matches the writer-director’s description of his earlier short, Spiral Jetty (2016), as “a spiral of incriminating information and distortions.” If there is a solution to the mystery of Notes on an Appearance at the center of its spiral, I have not found it, though certain themes are clear enough. One of them is the violent alteration of the urban landscape, either through construction—shortly before his disappearance, David muses on the erection of a new apartment building going up across the street from Todd’s apartment—or through destruction. “Most of this is gone now,” Keinitz-Wilkins says while thumbing through those pictures of old Romania, “Ceausescu destroyed most of this.” Among Taubes’s vacation videos, there is an image of the Twin Towers from the Staten Island Ferry, an image which as been captured thousands upon thousands of times, though here it’s imbued with ominous import. I don’t know the reason that D’Ambrose returns to the image of the Duomo, but I would suspect that it has something to do with its ability to seem both massive and, with its climbing lacework Gothic frill, delicate—the sort of thing imminently vulnerable to the promised attack on sickly order. The last sound we hear is that of lapping waves—perhaps peaceful, perhaps the harbinger of a rising tide.