Missing Persons

By Michael Koresky

Still Life

Dir. Jia Zhangke, China, New Yorker Films

Jia Zhangke, who has emerged as one of the great artists from the “Sixth Generation” of Chinese filmmakers, is one of those directors whose work will always be embraced and discussed by a number of devoted followers but whose discursive, searching approach to narratives and the people who inhabit them keep his films from appealing to a wider audience. At this juncture, I can’t recall any of his earlier features creating much of an art-house stir once they found distributors after their North American festival debuts; it’s a shame because, despite their refusal of cinematic conventions, Jia’s films are hardly ossified, self-contained art works—in fact, today there are no films reaching American screens that reveal quite so much about the state of contemporary China, as important a topic as anything else going on in the world today (despite the understandable glut of films on Iraq and Darfur).

As with his earlier Unknown Pleasures and The World, Jia Zhangke’s masterful Still Life is shot on digital video and skirts the line between documenting its nation’s transitional woes as it moves towards promised free-market independence, and creating fictional narratives around these events. Yet those descriptions can’t begin to illustrate the delicacy with which Jia surveys the scene, or the miraculous mixture of hope and despair that seems to spring from every moment he captures. For one thing, Jia embraces the video medium’s grain and slightly muddy hues to create something wonderfully, unexpectedly rich; much of Still Life (in an echo of the film’s English title) has a tint of chiaroscuro, casually placed tableaux of smooth bodies illuminated by pockets of natural golden sunlight, the camera drifting by.

What’s most extraordinary about Jia’s exquisite compositions is how fragilely rendered they are; Jia’s technique may be rigorous, but it never feels stringent, and character and setting always come before aesthetic rigidity, as with the work of Olivier Assayas or Maurice Pialat. Often his camera will capture a pocket of beauty, only to summarily move on, catching up with the people who inhabit the frames. And Jia has obvious love for those people, trapped between times, confused about their placement within rapidly evolving societies and urban environments at once crumbling and regenerating. In Still Life, Jia focuses on the intersecting lives of two characters, Sanming (Han Sanming), a coal miner seeking out his daughter, and Shen Hong (Jia regular Zhao Tao), concurrently searching for her husband, oblivious to Sanming’s quest.

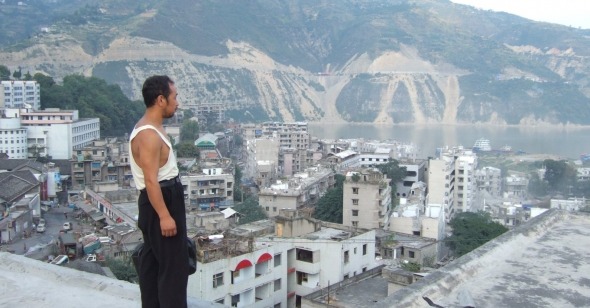

Both Sanming and Shen Hong have arrived at the Fengjie district, much of which has already been submerged in water, its citizens relocated, to make way for the Three Gorges Dam, a massive governmental project that has been in the planning stages for four decades, and was first envisioned as a deterrent for Yangtze River Valley flooding at the beginning of the twentieth century. With the high-profile hydro project expected to be the largest electricity-generating facility in the world by 2009, progress will come at the expense of the individual, so Jia, ever the humanist, looks at Sanming, Shen Hong, and all the others surrounding them, as full, lovely people who have become mere cogs in the wheel of time—even in the opening shot, a gorgeous, lengthy take of a boatload of ferry riders crossing the Yangtze River going in and out of focus, Jia already establishes the Fengjie citizenry as present and not present, flesh-and-blood made ghostly with a mere adjustment of the lens.

With his camera, Jia reasserts the primacy of people living in a culture that prizes things (the words “cigarettes,” “liquor,” and “toffee” all appear as intermittent on-screen text, opaque but never judgmental reminders of a fetishistic society). Yet Jia never gets bogged down in the particulars, or dubious responses to, supply and demand, taking a sometimes whimsical viewpoint—as when an amateur magician converts Euros to Yuan in the blink of an eye, or when Shen Hong and Sanming both witness a vaporous, fast-moving cloud sweeping over the submerged Fengjie with impossible agility. Jia looks at globalization with shrewdness rather than hostility, betraying a seeking nature as much as exacting cultural criticism. Just now coming out in New York after winning the Golden Lion at Venice way back in 2006, Still Life is a most welcome reminder of one of the most vital voices in world cinema.