Someone to Watch Over Me

by Nick Pinkerton

In the City of Sylvia

Dir. Jose Luis Guerin, Spain, Axiom Films

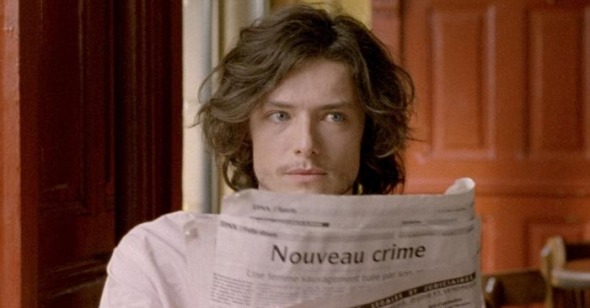

In the City of Sylvia, Jose Luis Guerin’s odyssey of perception, is so dedicated to getting inside the act of cosmopolitan female-watching, it might as well be called City of Women. Alert, feline-eyed Xavier Lafitte is a quiet young flaneur and diarist, an enigmatic figure introduced at loose ends in a summertime Strasbourg populated largely by drifting, bare-armed twentysomething sylphs.

Xavier’s vacation-quest is broken into three movements: First, Lafitte distractedly draining beers at the cafe attached to the local Dramatic Arts school, promiscuously selecting and discarding female clientele from his sight, scouring the crowd for, presumably, a suitable sketchpad model. Secondly, Lafitte indiscreetly stalking the beauty (Pilar Lopez de Ayala) his eye settles on, down boulevards and alleyways, across squares. Then, having found and lost his phantom, our man’s retreat to a bar-nightclub where, dialogue submerged by the playlist, a gallery of forbidding goth girls imperiously throw back his stare.

Strasbourg, a presence in every scene, bears no resemblance to the booming and bustling metropolises of silent-era “City Symphonies”—it’s a weekend town yawning with welfare-state lassitude; in the three days over which the film takes place, nobody seems to be working, save wait staff, some street cleaners, a fruit vendor. Guerin’s mode is a quietly bravura naturalism; a precise paring down of quotidian life into a vocabulary of incidents, spotlighting attention and elevating minutiae. The upsetting of a glass (a slapstick recurrence here) carries almost catastrophic impact. Save ambient chatter, the film is largely dialogue-free—urban musique concrete, including street musicians, is much of the soundtrack.

The cafe scene is a journey of shifting focus and sightlines, a minutely calibrated negotiation through the outdoor seating chart as our protagonist’s gaze traverses it; clientele are layered and overlapped, and Guerin shows his fondness for setting key moments in the dreamy collage of windowpane reflections. As City moves by, phrases are repeated—some passersby resurface (a face from the cafe returns in the nightclub crowd, a bent-legged flower vendor circulates through streets and shots), as well as intersections, a graffiti refrain, images (passing headlights crawling over a hotel wall announce the passing days). The viewer gets a certain pleasure from seeing this synchronous structure at work, and picking up the sense of an urban organism continuously functioning outside the narrative (the film shifts openly between extreme subjectivity and objectivity).

There’s a faint air of enchantment here, in the Grimm Rhineland facades of Strasbourg, the “missed connections” longing, an encounter on the tram (Lafitte and de Ayala miraculously lit at a seamlessly match with the cityscape outside, as though floating above it) that abstractly recollects the trolley of Murnau’s Sunrise. At times this can all threaten winsomeness, thanks in part to Lafitte’s achingly stereotypical “pale poet” vibe—the well-molded face, dandyish vest, sculpted tousle. But Guerin’s fable sometimes elegantly traces the outlines of an inchoate feeling: a scene with Lafitte waiting at a transit stop, surrounded by milling women in all shapes, colors, sizes (one with a trenchlike facial scar)—blooms into menace, the crowd into a miasma. It’s the raw heart of a movie that chronicles the pleasures and pitfalls of a prisoner of beauty.