Radio Days:

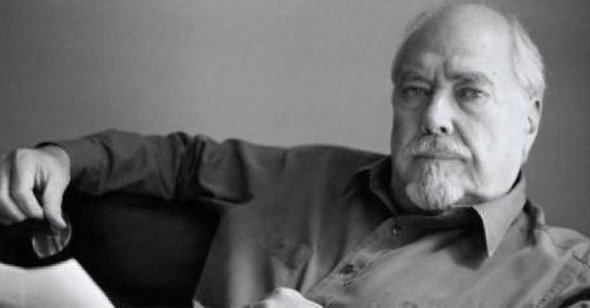

An Interview with Robert Altman

by Nick Pinkerton

Almost any praiseâor condemnationâI could drum up for Robert Altmanâs body of work would be redundant. What has he done for us lately? Aside from harangues against the Bush administration and public marijuana advocacy in prime "cantankerous old guy who doesnât give a fuck what anybody thinks" style, heâs directed a very fine, floating film from Garrison Keillorâs NPR institution âThe Prairie Home Companion,â a work that will doubtlessly cause critics to gush adjectives, and will perhaps even move some tickets by virtue of the materialâs cult cache and âtween-bait Lindsay Lohanâs serious-film âcoming out.â Itâs certain Altman wonât care about the critics, and I imagine the box-office only matters to him inasmuch as it helps the next movie find financing. He likes to keep working, to the extent that itâs hard to get a good picture of the size and the shape of his filmographyâthe multitude of projects, that army of characters. One question that remains consistent in my mind, when sifting through the man from Kansas Cityâs oeuvre: âHowâd anybody ever think to make movies like that?â

REVERSE SHOT: You had what might be called an apprenticeship period working in industrial films, as a screenwriter, in television; during that period, did you always have the specific idea of âmaking artâ through your vocation?

ROBERT ALTMAN: Making films was always my goal. Making entertaining films. You donât think about doing something in an artistic wayâyouâre either artistic about it or youâre not. I donât think thereâs any⌠I donât think you have any choice.

RS: In that sense, do you make any delineation between your film and television work?

RA: Itâs all part of the same book; different chapters.

RS: Is there work you did for television in the fifties and sixties that youâd like to have more widely available?

RA: I think I did a lot of good stuff, a lot of stuff Iâm very proud of. I donât know how to segregate that out⌠Itâs difficult, that stuff gets stuck in archives, gets stuck with lawyers, itâs too difficult for what the gainside is. Iâm very proud of the work I did on âCombat!â; I did a lot of things for a series called âBus Stop,â a lot of television work that I like a lot.

RS: Was there a point where working in TV became a constraint?

RA: Well, thereâs always a constraint, because you donât have the editing control⌠There are commercial restrictions to itâŚ

RS: One of the things that surprises me in watching something as early in your film work as That Cold Day in the Park (1969) is how fully realized your style was even at that pointâis that something that had become cogent in the TV work?

RA: That film was a chance to air out things, stylistically, that I hadnât had before.

RS: Were you plugged into what was happening in the European art cinema at that point? Was there a drive to make an equivalent American art cinema?

RA: I admired all those films: Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa, and I thought they were better work than what was being done in America⌠But they played to a different audience; thatâs why they were called âArt films.â

RS: Iâve noticed already in the critical reception to A Prairie Home Companion a tendency to call it a warmer, more humane Robert Altman movieâŚ

RA: If you pay attention to the critics thatâs your problem, âcause I donât. What they say about itâthey have to express their opinions to an audience that they know in a certain given number of words, and they do it in different ways⌠I donât think theyâre right, and I donât agree with almost any of them, whether theyâre pro or con.

RS: You wouldnât characterize Prairie Home as a more empathetic film?

RA: More empathetic than what? Itâs all about death, you know? I donât think Iâve ever done a film that has more to do with death as does Prairie, and if thatâs empatheticâŚ

![]() RS: So much of the movie has that elegiac, âsaying goodbyeâ quality, saying goodbye to people, to outmoded mediums⌠Since, in your career, youâve had the opportunity to see so much change in mass media, do you find yourself looking back with a sense of loss?

RS: So much of the movie has that elegiac, âsaying goodbyeâ quality, saying goodbye to people, to outmoded mediums⌠Since, in your career, youâve had the opportunity to see so much change in mass media, do you find yourself looking back with a sense of loss?

RA: No, I donât have a sense of loss, and I hope Iâm moving forwards, but I think weâre wearing out our audiences very quickly. I think already⌠Everything is kind of a copy of everything else. Thatâs why all these films are getting kind of tepid reviews and recommendations.

RS: Do you keep up with contemporary films to any extent?

RA: No, Iâm aware of their presence in the market, but I donât see a lot of them. City of God was the best film Iâve seen lately.

RS: When you talk about this watering down, what do you hold responsible?

RA: Fourteen-year-old boys. Thatâs the major audience. I donât think all these âX-Manâ pictures are being made for anyone else, do you?

RS: Could you imagine starting your career in this market?

RA: Sure. I mean, no matter where youâre put, you just deal with your generation and you deal with your own surroundings, today or a hundred years ago or a hundred years hence, it doesnât make any difference.

RS: In speaking of dying mediums: is your switch to shooting on HD a permanent move?

RA: Thatâs like talking about switching over from horses to motorcars; itâs switching from propeller airplanes to jets. HD is just a cheaper and easier medium to work in for certain kinds of films. I think itâs a good move forward. I defy any cinematographer, anybody, to look at Prairie and tell me whether it was shot originally on film or video. I did The Company on HD, and Iâm planning on using it in my next film.

RS: I know Prairie opened at the Fitzgerald in St. Paul, where it was filmed; how was the reaction from the faithful âPrairie Homeâ radio audience?

RA: Well, it was great in St. Paul, naturally it went very well. Most of the audience there were people who had been in our crew, our extras; we were there for quite some time making this film, everybody knew us. I wouldnât count on the gauge of what happens in St. Paul to be what happens in the rest of the country.

RS: Itâs interesting that thereâs no mention of Lake Wobegon in the film, moving away from what might be expected of a cinematic âPrairie Home Companionâ

RA: We went the other way; Garrison, originally, when he came to me wanted to do a Lake Wobegon film, and I went around the country and saw his show in different places. I said âI think we should just do your show.â And he agreed, but I think his preference wouldâve been to do a Lake Wobegon film, and Iâm quite sure he will in the future.

RS: In that you had Garrison both acting in the film and you were working from his screenplay, was it unusual practice for you to have a screenwriter so frequently on-set?

RA: I usually hire a screenwriter to be on-set all of the time. On Gosford Park I had the writer with me all the time; in Fool For Love with Sam Shepard, heâd written the play, and he was in it⌠The reality of whatâs written in a screenplay needs changes a lot of the timeâit depends on the casting and various elements that change. It isnât a frozen thing until itâs on film and put in a can. Garrison does his own show the same way; heâs re-writing in the middle of a performance, handing papers to people, keeping the script on him. Itâs a living, growing process.

RS: Youâve identified yourself in the past as a political filmmaker, and both you and Keillor are very public liberals. To what extent, if any, do you think of Prairie Home as a political film?

RA: In the world we live in, everything is political; itâs only when it gets to become organized politics that it gets to being oppressive and dangerous.

RS: Is it more than an accident that Tommy Lee Jones is a rapacious Texan invading St. Paul, one of Americaâs most liberal cities?

RA: Itâs not an accident, no. That was written and constructed and cast and shot with politics in mind.

![]() RS: The advent of DVD has made a much wider selection of your films available to an audience that might not have seen them on initial release. Are there any films of yours that youâre eager to see re-evaluated?

RS: The advent of DVD has made a much wider selection of your films available to an audience that might not have seen them on initial release. Are there any films of yours that youâre eager to see re-evaluated?

RA: You know one of the least successfulâin terms of audience and incomeâfilms that Iâve made was McCabe and Mrs. Miller. And you guys, and people out there say, âOh, thatâs a great film blah-blah-blah,â but it was a big, big failure when it came out⌠I guess it was saved by the criticsâŚ

RS: Is there anything you think still hasnât gotten its due?

RA: In my mind, none of âem did. Because Iâm looking at it from my own point of view. Each time I finished a film I thought, âWow, everybodyâs going to want to see this, this is gonna be the biggest film of all time.â