Roiling Below the Surface:

An Interview with Fern Silva (Rock Bottom Riser)

By Conor Williams

Fern Silva makes the most of film’s textural depth. His shorts, largely shot on 16mm, are entrancing, surrealist takes on ethnographic documentaries. Silva’s striking, lush imagery and ambient soundscapes lead viewers on a trip into a cerebral-cinematic beyond, while avoiding self-seriousness. His new film, Rock Bottom Riser, is his first feature-length work. Playfully stringing together various motifs, the film highlights the problematic construction of telescopes atop sacred Hawaiian land. Throughout the film, Silva freely flows from subject to subject: the search for extraterrestrial life, ancient seafaring navigators, vape tricks, Simon and Garfunkel, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

I met Fern Silva in 2017. He briefly taught at the People’s Film Department at Bard College following the death of Professor Peter Hutton, the white-haired patron saint of slow cinema whose landscape films mark my psyche to this day. Silva brought immediate warmth and enthusiasm to the task of teaching me and my classmates how to make 16mm films. I struggled for a while with the mechanics of it, but he set time aside for me, patiently guiding me through each step. In the darkroom, as I clumsily plunged my film strips into buckets of chemicals, his voice found me in the pitch black. He instructed me with care. It was a pleasure to reunite again on the release of Rock Bottom Riser—a trippy ode to Hawai'i focused on nature’s power, the vastness of time and space, and how history and identity intertwine.

Reverse Shot: This is your first feature film. I’m curious about what led you to explore the Hawaiian struggle for land preservation in Rock Bottom Riser.

Fern Silva: Back in 2009, the decision was made to build the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawai'i. I heard about that at the same time I heard about the opposition to it. So, I was led to it by the opposition, or the protest against it. I didn’t really know much about why it was happening, and it led me down all these avenues. It sparked my memory from when I was younger, and I was really obsessed with navigation and discovery. I knew then that the ancient Polynesian navigators were the greatest navigators to ever exist. What they were able to accomplish is probably the greatest feat in the history of humankind. They traveled from Asia six to seven thousand years ago to the rest of the Pacific and arrived in Hawai'i around two thousand years ago. So, thinking about this connection of astronomy and these telescopes on top of Mauna Kea in relation to the Polynesian voyagers, I felt like I had to find everything in between and investigate the massive transformation of Hawai'i beginning with the arrival of the first foreigners.

RS: The film is kind of fuzzy—not only visually, as it was blown up from 16mm to 35mm for the theatrical run, but also narratively fuzzy. Various figures are sort of collaged together. What would you say the film is essentially about?

FS: I arrived at the film with a particular perspective, a conversation with a group of activists. My interest was thinking about Mauna Kea as this symbol of resistance against corporate interest. But there are so many different viewpoints. It’s not black and white. Especially due to the arrival of foreigners. [James] Cook arrived in 1776. So, in terms of what it’s about, it’s more about raising questions. To make these connections, draw parallels, potential similarities…Part of the fuzziness is that I do like to think about movies as points of questioning. What the film tries to do is activate the viewer, and asks what it means to occupy space, and the effects of U.S. colonialism and assimilation. After spending so much time on the film, I thought it was important that I respect the diverse range of viewpoints.

RS: The main struggle in the film, I’d say, revolves around those big telescopes at the Keck Observatory and the indigenous Hawaiians who are upset that these have been built on sacred land. I just interviewed the author of a book about postmodernism, so I’ve been thinking about the notion that truth is relative, that scientific progress serves to further certain agendas. Do you think that science is upholding a white supremacist, capitalist, colonial project?

FS: Inevitably, the point is to arrive—as humans have throughout the history of our existence—to explore, discover, and arrive at a new location. What does that mean, for example, if we arrive on a planet where there is already intelligent life? Do we then obliterate that population? Simply based on the way things have occurred in the past? It’s tricky with astronomy in Hawai'i, because it’s not just the indigenous population who are against the telescopes. It’s really nuanced, and it’s important that we all know these nuances. There are foreigners and indigenous people that are for and against it. In terms of capitalism, and certainly the way Hawai'i has been affected since the 1800s, there are particular economies put in place. There are people who think that astronomy would bring in an astronomy economy that would have upward mobility, as opposed to the major economy being tourism. I think some people are sick of that. In terms of science upholding some level of white supremacy, yes, but it is nuanced. The argument that astronomers pose is that it takes many nations to build and work on the observatories, including the TMT on Mauna Kea, that they’re bringing people together and therefore should be celebrated. We’re talking about the U.S., Canada, Japan, China, India, and the list goes on. Many people, from many countries, continue building on sacred land. I would often hear from activists that telescopes would never be built on top of the Vatican, so why are they being built on Mauna Kea?

RS: Is there a particular reason, like a geographical reason, why it’s beneficial for those telescopes to be there?

FS: Mauna Kea is the tallest mountain in the world from the sea floor. Where it sits in the Pacific, and because of how high it is, the telescopes get to see more sky with less disruption. The reason they’re up there in the first place goes back to the ’70s. There was only supposed to be one telescope going up. It went up, much like the history of Hawai'i in terms of dealing with foreigners, certainly the first Christian missionaries that arrived, there was a level of soft power that was imposed. There was a tsunami that hit the Big Island, decimating everything. In a sense, the astronomy economy was able to come in and continue to pay a symbolic dollar for rent, because they were bringing in an economy. And from then on, multiple telescopes were built. The other thing is that Hawai'i is dealing with the military industrial complex. That’s a whole part of this as well. A lot of this preserved land is being taken and used by the military. You’re asking questions that are really important, and they’re on everybody’s minds, but when I got into making this film, I was coming from an activist perspective, solely based on the importance of the preservation of land and culture. When we talk about astronomy, I want to make one point—I’m not entirely against Western astronomy. The early Polynesian voyagers, they’re also astronomers! They were the first astronomers, in a sense, the first astronauts! Because they were able to navigate by the constellations in the sky.

RS: And it is a really remarkable feat, these telescopes and what they’re able to do.

FS: And they’re finding these other potentially habitable Earth-like planets. From those telescopes, we’ve learned a lot about what we haven’t known. The fact that there might be these places where we might eventually be able to go—it’s very likely, we just don’t have the technology yet.

CW: There are a few people in the film who give Herzogian performances, by which I mean in Werner Herzog’s documentaries something about the personality of the subjects makes them feel like a character. There’s the historical reenactor…

FS: While I was shooting the film, it was the bicentennial of the arrival of the New England missionaries to Hawai'i. Moses Goods is an actor and writer, and he’s performing the story of Henry Opukahaia, based on his memoirs. He was a Hawaiian kid who fled Hawai'i during the civil war of Kamehameha. He witnessed his parents and his brother get killed by Kamehameha’s warriors. He hopped on a ship and arrived in New York City, befriending Edwin Dwight at Yale, and became Christianized. I would imagine that his quick conversion had to do with the trauma from witnessing his family being killed and really took on Jesus. He wrote these memoirs before he passed away in 1818, and these memoirs were incredibly influential in the arrival of the missionaries. It was sort of a mini-bestseller at the time, influencing the American Bureau of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to sponsor the first New England missionaries to Hawai'i. So that’s why I put that in, because it was a defining point in the way Hawai'i was transformed. The reclaiming of Opukahaia’s Hawaiian identity is what shifts the original story.

RS: I could sense Sky Hopinka’s influence on this. He did audio recordings for this film.

FS: Sky actually just came with me to record one scene, with Moses in New England. But yeah, I love Sky. He’s like a brother to me. Mike Stoltz also did some recording, and I did a bunch.

RS: There’s a soft psychedelia to the film. What can you tell me about that feeling?

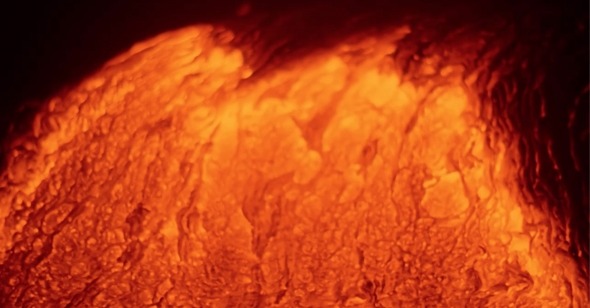

FS: I think that natural phenomena can be pretty psychedelic, so I can see why. I mean, we’re looking at these landscapes that have been preserved and constantly erupting. The Big Island is made up of multiple volcanoes from different periods of time millions of years apart. So there is something very prehistoric or otherworldly, and that could seem sort of psychedelic. Just looking at lava and listening to what it sounds like, because that’s not normally something you get to listen to. In a sense, I think there’s an inherent durational psychedelia there.

RS: There’s a shot before the title card, this breathtaking long shot above a volcano. How did you pull that off?

FS: I did all the other aerial stuff, but that shot was not shot by me. It was shot by a Hawaiian filmmaker who mostly just shoots by helicopter, and he asked me what I wanted, and I said, “Well, I’d like this long take of the lava.” And he was like, really? Nobody really wants a take that’s like, three minutes long, so it was kind of interesting for him to do in the first place. For the other aerial stuff, I went up with David Okita, who’s a pilot in Hawai'i. There were no doors on his helicopter. There was a point when I’m up there with my Super 16 camera, and he was like, “Holy shit, Fern. Your entire body is out of the helicopter. You have to at least put half of your ass cheek in the seat.” There are no drones. It’s all helicopter footage.

RS: Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson makes an appearance of sorts in the film. I’d say this is probably the only experimental film you can see him in.

FS: He’s half-Samoan, half-African American; he grew up in Hawai'i, and he’s really proud of his ancestors and his history. And he did go up to Mauna Kea to be with the protestors and stand with them. He’s a superstar.

RS: And that’s surprising to me. It seemed like a genuine display of solidarity with a cause.

FS: Absolutely. It makes a massive difference. I mean, what he says is a bit surface, but still, that he’s there makes a huge difference. He’s also supposed to play Kamehameha, the first Hawaiian king, and there’s controversy revolving around that, because of his ancestry. Throughout the whole film, when you ask what it’s about, there are meta-levels of meaning that I’m trying to connect. That’s just how I make films. It can’t be just this one clear narrative. There are multiple meanings behind everything. With the Polynesian voyagers, we’re looking into the past. With astronomy…the speed of light is so slow. With the arrival of foreigners, we’re also looking into the past and seeing what it’s done to the present and potential future. With Dwayne Johnson, he’s at this present that’s sort of morphing like the lava is, but he’s also playing this role in a film that will be made in the future, we’re just not sure how it’ll expand and solidify. Also, I like Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. I think he’s a good guy. I don’t relate to his masculinity at all which invokes a hyper-hetero mentality. I just don’t. But he seems like a sweet guy. Even Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle is kind of a heavy film that deals with identity in popular culture.

RS: You know, when I saw that film, I actually brought it up in Ed Halter’s queer cinema class. It’s an interesting body swap film.

FS: It is! Nobody does that! I’d like to think that maybe it promotes some tolerance about identity and sexuality to a larger audience. So maybe that was really influential, too.