Earthly Origins

by Edo Choi

Born into a generation weaned on home video, I recall always having a vague sense that the theatrical movie experience was distinct and special, but I only began to form a consciousness of how, and why it was worth defending, while attending the University of Chicago. The conversion occurred at Doc Films (affectionately, just Doc), the University’s film society. I reside and work in New York City now, but it’s the people I met at and through Doc, the immediate environment of the Hyde Park neighborhood, and the larger city of Chicago that continue to feel like my true home in respect to cinema. Doc wasn’t the birthplace of my interest in movies, but it gave me an experience of them as a communal and tactile pursuit.

Decades before the formalization of academic film study and the advent of home video, film societies arose as a grassroots movement for the cultivation of what today we might call an alternative film culture. The likes of Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16 repurposed the 16mm rental market, geared toward institutional spaces, to express a localized curatorial sensibility and address an audience the mainstream film industry considered marginal. Founded in 1940 as the Documentary Film Group, Doc entered this history as a society for the study of the nonfiction film. By the fifties, the group had become a genuinely activist enterprise, showing banned films like Salt of the Earth and hosting avant-garde filmmakers like Maya Deren. At the height of Andrew Sarris’s influence in the sixties, the society developed into a stronghold of auteurism with a reputation for producing particularly zealous film critics. “He’s one of those ‘Doc Films’ types,” wrote Roger Ebert of Dave Kehr, once Doc’s president. “He’d apparently seen every film ever made by the age of 20…” In 1987, Max Palevsky endowed the renovation of the gymnasium at the University’s Ida Noyes Hall into a nearly 500-seat cinema. From that point forward, Doc operated as something like a genuine, non-theatrical venue with 35mm projection, repertory programming that ran throughout the week, and second-runs that brought in money on the weekends—a model which, more or less, continues today.

For me, Doc was a time and place of pure discovery, before such inconvenient considerations as earning a living and charting a career path entered the picture. It’s where, in my first year alone, I discovered not only Jacques but Maurice Tourneur; where I became acquainted with Robert Ryan and, through him, Max Ophuls and Nicholas Ray; and where I saw an epochal screening of Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life, the climax of which literally raised the hair at the back of my neck. Not all of Doc’s quarterly calendars were created equal, but the organization’s democratic programming model, where any and all comers were invited to propose series and participate in quarterly votes, afforded a breathtaking diversity of historic and aesthetic interests. Summer 2008, the first quarter over which I presided as programming chair, a role I would hold for the better part of the next three years, was a cinephile’s paradise from silents (F.W. Murnau’s Tabu) to avant-garde features (Joyce Wieland’s La raison avant la passion, Larry Jordan’s Sophie’s Place) to auteurist deep cuts (Andre de Toth’s Slattery’s Hurricane, Raoul Walsh’s The Bowery). The following autumn quarter, I remember with fondness the niche survey “Oy, Revolt!: Socialism, Modernity and Political Intrigue in Yiddish Cinema,” which included Edgar Ulmer’s sublime, seldom-seen The Light Ahead. Last but not least, in Spring 2009, we mounted a personal dream program on the New Taiwan Cinema, for which the distributor struck a new 35mm print of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s A City of Sadness.

We enacted at Doc a kind of living, open-ended film seminar—only a handful of us chose to pursue the University’s Cinema and Media Studies major—with the freedom to follow our curiosities unburdened by traditional canons, hierarchies of taste, or academic narratives of film historical progress. Doc promoted whatever cinema any one programmer could convince the rest was worth promoting, delved into whichever obscure nook of film history seemed worth excavating. Although one of us might poke irreverent fun at another’s overzealous pronouncements or far-out stances, we always remained supportive of each other’s efforts in practice—a true community. Doc didn’t just allow us to access film history; it allowed us to express, in however humble a fashion, our own place within it and within contemporary film culture, one that only lives as a social endeavor carried out and fulfilled in a collective space.

***

New York City is known for its unmatched wealth of film venues. I was born and raised here, but like many of my peers who moved to the city during or after college I’ve often felt like a lonely migrant to its sprawling nexus of repertory film programs, art houses, film festivals, and museums, as well as the throng of dedicated programmers, distributors, filmmakers, and writers, not to mention audiences, who enrich and sustain it. As with most aspects of the city’s cultural life, film in New York comprises more of a scene than a community, which is not to diminish the genuine forms of community so many of us strive to cultivate. Indeed, right now, communal gestures such as the Cinema Workers Solidarity Fund seem like the only sources of practical recourse and spiritual uplift we have, especially for those of us who, hopefully only for the short term, have lost our livelihoods.

If New York has felt like a second home in cinema for me personally, it’s not only because of how large Doc has loomed but also because I did not initially discover my passion for film at a Film Forum or Film Society of Lincoln Center. As a child, my parents and I frequented the now long gone Olympia Theatre on Broadway at 107th Street (then operated by Cineplex Odeon), the likewise defunct Clearview Metro Twin at 99th Street (the building still stands unfilled today), and the gigantic Sony Theatres (now AMC Loews) Lincoln Square at 68th, the opening of which in 1994 I vaguely recall with its then-novel IMAX screen and kitsch mockups of old movie palaces adorning the auditorium entrances. These mausoleums of mass entertainment remain forever associated in my memory with the likes of Star Trek: Generations and Crimson Tide, Jumanji and The Rock, Bowfinger and Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me.

Revelation, however, only first struck in the private space of the home, first on VHS, and later the futuristic-seeming DVD with its promise of superior quality and special features. I was a little too young and square to have known about the East Village’s storied Kim’s Video, but on the Upper West Side I did have Gary Dennis’s Movie Place, the scrupulously amassed collection of which kept family movie nights packed through my high school years.

An elder film critic once wrote me that the transmission we receive from a work of art, the greatness we perceive in it as that direct umbilicus from the artist(s) awareness to our own, “is a fragile accord between a lot of contingencies—never ultimate, always provisional.” In this sense, material conditions of reception might be, well, immaterial. “You change, your mood changes, your angle of vision changes in ways you can’t account for.” What difference does it make if you experience a film at home alone or with family as opposed to experiencing it in a theater with a crowd, let alone on a large screen as opposed to a little one, or even on a 35mm print as opposed to a DCP? Putting aside considerations of audiovisual fidelity, and, when it comes to experimental films in particular, of medium and site specificity, most of the time it’s not the film that changes, but we who change. The question of what we really lose when there are no longer any movie theaters loses its salience and urgency if we view it too closely from within the logic of particular films we’ve seen and film experiences we’ve had.

At age twelve, I experienced the epiphany of Goodfellas on tape. Watching the Steadicam glide through the underbelly of the Copa, my mind lit up with the recognition that movies were made by people, not beamed down from on high. All this had been carefully orchestrated for my benefit in accordance with someone else’s peculiar, and, in this case, peculiarly seductive, vision of the world. I’ve seen Goodfellas many times since that day, including once on 35mm in the Sumner Redstone Theater at Museum of the Moving Image, where I had the honor of privilege of working for the last year. Over time, Scorsese’s film has risen and fallen and risen again in my esteem, but no matter how great a film I assess it to be at any given point in my life, I don’t think I’ll ever recover the shock and rapture of that first experience, which did not occur at the cinema.

On the other hand, I saw another film for the first time during the Museum’s Scorsese retrospective, the often maligned The Color of Money. Here is a film that might not compare to its iconic predecessor The Hustler in terms of the weight of its action or the stakes of its storyline, but Color is all about luxuriating in a certain atmosphere, in thickly evoked sensations of taste and smell, and in the dizzy motions and cadences of the game of pool itself. In other words, it’s a film of and about tangible pleasures as only cinema can convey them. I’m sure it does the trick on Blu-ray; on 35mm it laps you up.

I think cinema, if not so much the movies, has something precisely to do with this haptic register: the almost synesthetic sensation of an audiovisual experience becoming a palpably felt one, or perhaps, more simply, the feeling that the screen, and the space it contains, reaches down to touch you and that you in turn might reach up to touch it. It would probably be folly to try to elaborate this intuition into a coherent theory of the phenomenological difference between the cinema screen and other types of screens, or between the digital and photochemical image. For now, I can only submit, that the moment I became aware of an experiential distinction between these sets of conditions, the haptics of cinema spaces, even those whose images are digitally projected, have always felt more sympathetically and rhetorically potent than those of home spaces.

Today I keep returning to something Stan Brakhage said: “I’m involved in touch, in touching, in knowing people, in dealing with them in three dimensions, in smell, and so on, not obliquely through some laser beam reconstruction…” Every time I think of a friend, colleague, or family member I have been unable to see, embrace, or simply share physical space-time with, I think of these words. And every time I watch a film on my computer, I think of the loss of that same space-time relationship with respect to a film, how the viewing experience feels, regardless of how high or low the resolution, somehow diminished and distant, thinner and fainter. I yearn for the signs of physical contact that are unique to cinema, and especially to 16mm and 35mm film projection, those qualities that quicken our hearts like grain and flicker, or, absent those, the basic sense of shared concentration in public space as at a house of worship, of illusory distances on screen that nonetheless become physically measurable in terms of relative scale and distance to the screen itself.

This familiar mise-en-scène of the cinema space finally feels more agreeable to my sense of myself as a physical being than the space-time vaporizing mise en abyme of online streaming and other forms of home viewing. In a cinema, a movie affects me like a happening, almost, as André Bazin famously put it, “a natural phenomenon… a flower or snowflake whose beauty is inseparable from its earthly origin.” I’m not arguing for a new ontological construct, merely, as Bazin in fact himself was, pointing out a psychological fact. Perhaps we need Bazin now more than ever in the era of content, a little dose of classical realism to cure our reality apathy.

***

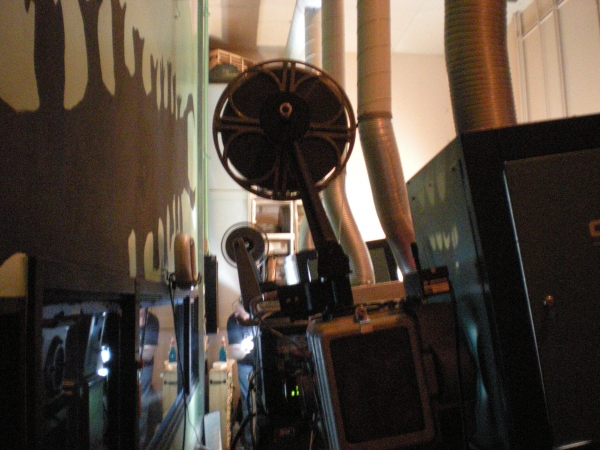

I saw many great movies for the first time at Doc, but more than the film history I acquired there, I feel I learned to distinguish and value cinema itself as I’ve attempted to define it above. Certainly to be at Doc in the late 2000s was to learn to appreciate the physicality of film with a peculiar acuity. At that point, 35mm was still the chief format for both theatrical and non-theatrical distribution, as well as repertory circulation. In my first couple years, nearly every film Doc screened we did so on either 35mm or 16mm prints. Simultaneously, our awareness of the coming digital changeover heightened our sensitivity to the fragility of the state of affairs under which we were operating. The projection booth at Doc remains a sacred space in my mind with its pair of Simplex XLs, affectionately nicknamed Evelyn and Wanda, and the giant painted black silhouette of the Tingler, in honor of William Castle’s classic gimmick film of the same name, that adorns its front wall. It was under that sign that I learned to inspect, prep, thread up and run film.

One print I both projected and watched, and that I’ll never forget, was a pristine copy of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Millennium Mambo, which we booked from Palm Pictures in that beautiful summer of 2008. There’s perhaps no better film to encapsulate the change my relationship to cinema had undergone since the night I watched Goodfellas. Scorsese had been my first inspiration, but Hou Hsiao-hsien had grown most important to me in my first two years at Doc. He remains a favorite filmmaker, one whose work has always felt uniquely attuned to the origins of cinema as a modern art form, bound up in the twin legacies of industrial capitalism and colonialism. The cinema screen itself is constantly referenced in Hou’s films, from the sudden apparition of an actual screen flapping in the wind in a rural village square in Dust in the Wind to the vacant movie theater where the bumper car sequence of Bresson’s Mouchette plays against the blank wall where a screen once hung in the exquisite short The Electric Princess Picture House.

As I watched Millennium Mambo at Doc, it seemed to speak eloquently to a world where the haptic, that relationship to others and to our own lived environment through direct physical contact, was already giving way to the borderless spaces and smoothed out surfaces of a digital existence. Its ending is a vision of an empty, snow-covered street by night, bedecked with old movie posters, in the former coal mining town of Yubari in Hokkaido, Japan. The posters are hung for a film festival, but Hou never shows the event itself. Instead, he invites us to contemplate these images as inexplicable relics from a remote past, gradually disappearing under a blanket of snow. The town’s post-industrial context gives this scene a hint of the apocalyptic, but it feels more mournful than final, a glimpse of what movies might become without cinemas to house them.