Movie of the Moment (for Worse): The Hateful Eight

On this very website, Reverse Shot lifer Nick Pinkerton referred to Quentin Tarantino’s latest offering as “a bloated, torpid, and largely graceless piece of work.” Another longtime RS contributor, Adam Nayman, said of the same film in the pages of Cinema Scope: “The Hateful Eight may really be sort of terrible.” And at Vice, RSer Ashley Clark called it “a sickening experience; three-plus hours marooned in front of the projected fulminations and fetishes of an untrammeled egotist.” I can’t say I much disagree with any of these very smart gents, which is why I’ve found the regular drift of my thoughts back to The Hateful Eight more than a little perplexing. Why haven’t I been able to let this bloated, torpid, sort of sickening whale of a film just drift off to sea? Perhaps it’s because that at the tail end of a just-god-awful year here in ‘Murica, in which indignities and horrors were manifold, and our society, at least as refracted by our news media, seemed strained in every direction, The Hateful Eight washed up on shore at 2015’s end with a thud and seemed to encapsulate it all. Though set during the Reconstruction, it’s a readymade Cliff’s Notes of shitty late-Obama America: Whites hating Blacks; Blacks hating Whites; both hating on Latinos and all feeling pretty ok about abusing women as well. In this world, guns are everywhere, authority is fleeting, the profit motive reigns supreme, memories of the Confederacy loom large and an absent Lincoln, unable to defend his legacy, is just left twisting in the breeze.

Now, noting that these are elements in a film is quite a different thing from arguing that they’re marshaled toward a designed end. Tarantino’s had a spotty record, at best, in this regard, seeming most adept through his career when he’s purposely unpacking and diagramming the machinery of the movies themselves (his two best films: Death Proof and Inglourious Basterds) than anything at work in society at large. In his other films, he’s proven himself a kind of voracious cultural sponge that locates and soaks up latent tendencies from the ether and repackages them—see how he condensed the Clinton era’s hunger for anything resembling the countercultural (Pulp Fiction) and the mainstreaming of fascination with black culture (Jackie Brown), or how Kill Bill Vol. 1 seems born from that early aughts moment of global cultural proliferation. It’s this ability that’s allowed him to remain so popular. And it’s this sensitivity that makes me wonder to what degree The Hateful Eight is an awful, miserable sit on purpose, while knowing full well that this is a dog-chasing-tail argument.

So, after his biggest box-office success, one of our most obnoxious filmmakers made a movie whose worldview lines up with the Republican presidential debates or a Donald Trump rally. I’m writing this just as CNN announces that Sarah Palin has endorsed Trump for president, the most noxious nexus in American political life in quite some time. This is the one of QT’s movies that might have more to tell us about itself, and us, as it ages. It functions as the opposite of Reverse Shot’s best film of the year, In Jackson Heights, which shows Americans our best selves. The Hateful Eight may not be the Quentin Tarantino film anyone wanted, but it may be the Quentin Tarantino film we deserved. —Jeff Reichert

Most Balletic Cinematography: Maryse Alberti for Creed

The elaborate, extended, and rightly celebrated single take of the first fight scene—swooping, dancing, jousting—is not the only impressive achievement of Alberti’s dazzling work on Ryan Coogler’s Creed. Throughout, Alberti recalls the earthy, everyday quality that made the original Rocky such a tactile and relatable experience, without ever calling attention to itself as nostalgia—the fallback of any franchise entry. Since nostalgia for childhood favorites holds quite a lot of currency in our infantilized culture, Creed was a refreshing surprise, an entry in a successful film series that took the time and care to sculpt out a unique space for itself. Much of this had to do with cinematographer Alberti, whose collaboration with 29-year-old director Coogler made for one of the more exciting developments in mainstream American cinema in 2015. The frustrating epilogue is that Alberti could have been the first woman nominated for a best cinematography Oscar (is that true??) and was not. No matter, as both the original Rocky and Creed knew full well, one doesn’t need a prize to be a winner. —Michael Koresky

Worst Director: Judd Apatow, Trainwreck

Judd Apatow has remade American movie comedy in his slovenly image, and it’s an extreme makeover worth critiquing. His methodology—such as it is—is to plunk the camera down in proximity to talented mainstream comedians, wait for them to knock their line readings out of the park, and then solder the results together via plodding shot-reverse-shot editing. There’s rarely any wit in the camera placement or the placement of the players within the frame; whenever more than two people share a composition (which is rare) the indifference of the background acting is startling. Apatow’s latest movie isn't his worst. It’s shorter and less stultifying than This Is 40. But its lack of craft is connected to its lack of basic credibility. The same self-satisfied power-gaming that motivates this mogul to round up Matthew Broderick, Marv Albert, and Chris Evert for cameos just because also accounts for storytelling lapses both small (why is Bill Hader accepting an award at a fancy ceremony in the middle of the day with light streaming in through the windows?) and large (how does Amy Schumer pitch, write, fact-check, and deliver a long-leadpiece to a glossy magazine in what feels like a day and a half?). Gripe all you like about Trainwreck’s pat, happy ending and wobbly sexual politics—they’re both #problematic—but the biggest problem here is the unchecked laziness of a filmmaker in his full, undisciplined glory. Contrast his 2015 grosses with those of his swifter and more innovative protégé Adam McKay, who made interesting and unexpected aesthetic choices throughout the comparably mainstream-aimed The Big Short and ask yourself why Apatow should ever hope to improve. —Adam Nayman

Best Throwback: Bridge of Spies

Spielberg’s wholly untrendy dramatization of a true tale of Cold War heroism is pure Hollywood craft of the kind we no longer see, with an undercurrent of Capra-esque liberal humanism so genuine it could make today’s cynical progressives blush with a mixture of horror and envy. Nothing from the once-upon-a-time dream factory in 2015 was as exquisitely controlled. One can only hope that some future filmmaker is taking note; unfortunately the film radiated the constant sense of being among the last of its kind. Bury me with it.

Worst Throwback: Fifty Shades of Grey

Oh, so that’s why they stopped making big-budget “erotic” dramas . . . because they’re horrifically sexist, reductive slop that cater to the widest swath of the public’s most vanilla outré fantasies and they can’t help but be mechanically performed by a cast of tinsel-town newbies with nothing/everything to lose uncomfortably doffing clothes on set while hoagie-eating crew members stand around waiting for the day to end. In case you forgot: there isn’t a single person on earth who thinks that Adrian Lyne made good movies. Probably not even Adrian Lyne.

Most Throwback: Star Wars: The Force Awakens

If there was a scene in J. J. Abrams’s amusing, well-paced, nicely acted, and entirely anodyne Star Wars reboot that wasn’t in some way adapted or updated from a corresponding scene in the original Star Wars—and therefore familiar to the scenarios I enacted with my Star Wars toys back in 1983—please tell. Inquiring minds want to know. Cute new bot, though. —MK

Best 3D: Every Thing Will Be Fine

Wim Wenders’s 3D-shot James Franco-starring domestic drama Every Thing Will Be Fine limped into U.S. theaters after being roundly thrashed at its Berlin premiere. Criticisms of this one were many, varied, vicious, and not wholly unwarranted, but most came bearing that gleeful sense of sharks circling wounded prey. Wenders’s fiction films have been rather underloved over the past two decades; his last narrative film, 2008’s earnestly silly, but unfairly maligned Palermo Shooting, didn’t even get a single U.S. screening until this past year. Meanwhile, his nonfiction work has won near-universal plaudits. Every Thing Will Be Fine is no masterpiece, but it is a return to some kind of form. Its story, of a handful of damaged lives interconnecting at various points in a bit over a decade isn’t anything new (this same film could have been made by Atom Egoyan in the late eighties, and not just because it’s set in Canada—perhaps I’m damning with faint praise?). But Wenders’s choice to film a drama of mostly interiors in 3D is something we haven’t seen much of. Thus we have a movie in which each inside master shot gets separated out into a series of planes; foreground, middle ground, and background seem pasted together almost on purpose, lending everything in the film a sense of unsettled construction that dovetails the narrative’s twists and turns. Close-ups, especially, take on a unique strangeness here. It’s a new idea of how 3D can be used. And while it’s not necessarily a great one, there’s something in it that makes you lean closer to the film, and this is so different from how the technology is usually employed, making audiences shrink away from objects flying in their direction. —JR

Best Back-Patting: Spotlight

Of all the myriad reasons that All the President’s Men is an American movie classic—and it is—one is that its depiction of the (perceived) glory years of investigative journalism coincided with the (putative) glory years of film criticism. Way back in 1976, it was just as plausible that some swashbuckling auteurist could shape the entire conversation around an easy-riding bull-rager’s latest as it was that two reporters could take down the President of the United States. Alan Pakula’s (I should say: brilliantly made) film was given a hero’s welcome by ink-stained wretches grateful for handsome fantasy projections of the likes of Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford. Few movies have twinned righteous indignation and relaxed flattery so masterfully. Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight doesn’t match its spiritual predecessor in this or any other department—its inferiority as a Serious Grown-Up Oscar Season Entertainment is summed up by the trade-down from Jason Robards to John Slattery as two generations of Ben Bradlees. (He was better in Wet Hot American Summer: First Day of Camp). But the raves it’s getting from a (mostly) older guard of critics hint that it’s striking a similar chord in a very different moment. For writers old enough to remember the Internet being discussed by editors as a niche supplement to print coverage (insert amused emoji here), Spotlight’s scenes of reporters pounding the pavement are fondly nostalgic. For their Word Pressing usurpers, who’ll probably never get a desk job (at the Boston Globe or anywhere else), it’s like a slice of science fiction seen through an envious, emerald-eyed filter. I won’t go as far as others in suggesting that Spotlight enshrines its heroes’ sacrifices in lieu of greater focus on the suffering of survivors of sexual abuse. But it seems to me that the main takeaway from this movie is that the media is the true, thin blue line between corruption and justice. They should have called it Limelight. —AN

The Definitive Ranking of 2015’s Lone Wolf Survivalist Films: The Good Dinosaur > The Martian > The Revenant

Best Failed Franchise Launch: Jupiter Ascending

In a year in which forces woke and other superpowers drifted into senescence, the birth of yet another goddamn mega-franchise is not exactly big news. And maybe it’s for the best that the Wachowskis’ batshit space torpedo was so widely derided that it shall spawn no more part-human, part-canine star children. But for all its absurdities—including space-Rollerblades, an insanely convoluted plot, and Channing Tatum's doggie ears—Jupiter Ascending is wildly entertaining. With its byzantine interstellar architecture and über-operatic take on literally star-crossed love, it’s closer in scope and tone to ’60s SF literature (especially Samuel R. Delaney, a Wachowski hero) than that of the dour, scientistic, NASA-certified variety so much in fashion. Add to that an awe-inspiring performance by Eddie Redmayne that hits truly cosmic levels of camp, and you have two hours of actually daring, if not exactly original, science fiction with—better yet—no option of renewal. I wish I could say the same for Sense8. —Leo Goldsmith

But What About . . . Kyle Chandler in Carol

“I was pulling for Chandler. I just dig that dude,” riffed Andy Samberg at the Emmys after Kyle Chandler (Bloodline) lost to beloved, obviously due Jon Hamm (Mad Men). But he’s not the only Chandler Man. With his longtime work on Friday Night Lights and a slew of other shows, the actor’s TV resume is upstanding, but it’s in film roles large and (mostly) smallish that I’ve fallen in like with the inoffensively blandsome actor’s quiet, unshowy talent. There’ve been some duds, but in 2013 he was brilliant in his few scenes in The Spectacular Now as an alcoholic absentee father, not giving into the actorly temptations of that description. And in The Wolf of Wall Street, wearing the standard issue black suit of the FBI, he managed to embarrass Leo DiCaprio’s Jordan Belfort on the latter’s yacht by playing it straight, with the smugness of patience, unaffected by Belfort’s confetti shower of “fun coupons” on the way out. Todd Haynes, surely sensing the actor’s Rock Hudson qualities, gave him his best film role yet in Carol. As the husband dwarfed by the central lesbian romance he can’t control, the still-sympathetic Chandler makes an impression. It’s Carol and Therese’s story, but Chandler helps make Harge’s role in the thwarting of that relationship not one of mere malice, but one that arises from personal insecurity, fear of scandal, received prejudice, and misguided fatherly protectiveness. When Cate Blanchett delivers her devastating “We’re not ugly people” to him, Harge receives the wounding truth in kind, and Chandler plays that brief collapse of litigious rancor perfectly, movingly. —Justin Stewart

The Flatline Award (tie): Jason Segel in The End of the Tour and Jamie Dornan in Fifty Shades of Grey

Clearly one of these performances is better than the other. I’ll let you decide which. That said, what these two men had in common in these films was an ability to deliver each and every one of their lines in a stultifying, completely flat monotone that become unbearably grating as the hours wore on. For Segel, it was an attempt at mimicry, as he was playing David Foster Wallace as a lovable, bandanna’d teddy bear; for Dornan, it seemed a terrified attempt at dulling his Irish brogue, with the last syllable of (I’m pretty sure literally) every single sentence dipping down to the soles of his shoes rather than lilting up to the rafters. Whatever the reasons, these actors’ one-note vocal tics ended up speaking for these entire films, which so often devolved into mannerism and posturing. —MK

Subprime Cinema Award: 99 Homes

It’s unfortunate that the only film that dares to address the millions of Americans who believe themselves to be temporarily inconvenienced millionaires is so unpleasant to watch. In other words, it’s not from the perspective of slick “greed is good” suits living it up at totally sick parties until the deus ex machine kicks in, but more reflective of the target viewer’s point of view. While there’s much to be said about its Ramin Bahran-ian blend of moralistic sappiness, I was more put off by its overly twitchy star, Andrew Garfield, and how an actress of Laura Dern’s caliber got stuck with such a lousy, underwritten supporting role: not just “The Mom,” but “The Grandma”! A subject and approach this important deserves a mulligan. —Violet Lucca

Best Look: Carol

It starts with a look. Not the one Thérèse and Carol share across the department store floor, but the look Haynes and his DP Edward Lachman have chosen for Carol, the film. The grain is deep and the Technicolor dreamscape of Far from Heaven not in evidence. A nondescript, bleached teal-green slides across the titles: a box from Tiffany dropped in a muddy puddle and wiped down; a layer of dust on New York City . . . then, cutting through the gloam, the odd flashes of red (Carol's lips, Therese's coat) like rubies, nestling on a murky river bed, catching the light. It ends with a look too: crisper and cleaner than before, as if Thérèse and Carol's world has started to become more defined: a world where their pleasure and glamour might be allowed to emerge from the shadows. —Julien Allen

Most Metaphors: Manglehorn

David Gordon Green is a modest filmmaker, but he lays his modesty on with a trowel. If the extended dream sequence of a car accident riddled with busted watermelons wasn’t enough; if the Al Pacino character’s profession—he’s a keymaker who can’t unlock the key… to his own heart!—weren’t clear enough; if even the conclusion of the film, in which our protagonist puts all his burdensome belongings in a rowboat and sends it off to the dump so he can start over again, weren’t head-bangingly obvious enough; there’s more: a final Grace Note™ in which Mr. Manglehorn has a last interaction with a mime, in which the wise and wordless one helps him use an invisible key to unlock a car door. —MK

Worst Eating Habits: The Cast of Spotlight

In Tony Scott’s worthless remake of The Taking of Pelham 123, the MTA dispatcher played by Denzel Washington is a stressed-out, blue collar workaholic, his bodega coffee bona fides driven home by the junk food props he’s inhaling in seemingly every scene. In the blandly workmanlike, visually miserable (because—didja hear?—it’s all about process) Spotlight, which for some reason wasn’t an HBO movie, director Tom McCarthy falls back on the same shorthand, stuffing his actors’ faces with quick slices and cheap Chinese whenever possible. The point is, these Boston Globe investigative soldiers are so focused on leads, sources, and systemic hurdles that diet is an afterthought. When you’re working to expose wrongs as wicked as those being uncovered here, there’s scarcely time for farmer’s market Sundays. So we get Mark Ruffalo forking a hot dog into a pot in his sad, trouble-in-paradise studio (shades of Channing Tatum’s stark solo ramen repast in Foxcatcher) and Michael Keaton mindlessly devouring whatever’s handy, his eyes never noticing the food he’s shoveling in. Stanley Tucci, not a journalist but an also tunnel-visioned attorney, enjoys a long noodle-slurping exchange. While it’s no doubt accurate that story-chasing journalists aren’t fastidious carb-counters, Spotlight’s pathological emphasis on their distracted slobbiness is as oversold as Ruffalo’s spastic hectoring. —JS

Best Eating Habits: Carol

Creamed spinach over poached eggs with a martini chaser soon becoming the new Brooklyn brunch. —MK

Most Revived: Wim Wenders

This art-house stalwart not only received a month-long retrospective at New York’s MOMA (though this one suspiciously stopped showing his narrative films with Faraway, So Close), but also another one downtown at the IFC Center which dredged up rarities like The End of Violence and Palermo Shooting. Many of the remastered versions that screened at both venues are currently on tour across the world. Why so much Wim and wigor in 2015? Is it that a generation of film buffs who came of age on these films have now grown into respectable programming positions at major venues? No matter, it’s good to have Wim back in the conversation. —JR

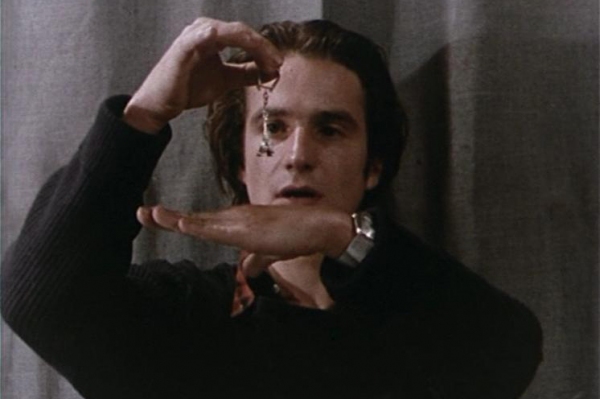

Funniest Trailer: The Sound and the Fury

Did the unstoppable James Franco’s adaptation of William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury come out? I have absolutely no idea. I don’t remember there being any reviews of it, and I feel like I would have been made aware of them if they existed: the trailer was so raucously funny that it’s unlikely the film could have been any less. It happened so unexpectedly: Faulkner’s masterpiece—surely one of the great works of art of the twentieth century—was suddenly a cheap-looking digital feature with performance-artist cum culture-destroyer Franco not only directing but also starring as literature’s prototypical man-child Benji, sporting effed-up false teeth that looked like the dentures of a Quasimodo costume rented from Halloween Adventure. The trailer features all manner of hilariously stilted line readings from a cast of unknowns in period dress, but nothing seared onto the brain like the slow-motion dolly into Franco’s three-toothed Benji gawping and snarling behind a rude wooden fence as though a caged velociraptor or Jonathan Demme’s Beloved just as she’s about to disappear. Bonus points for Franco buddy Seth Rogen’s wordless appearance in the trailer as what looks like Van Gogh’s friendly postman. It’s a giddy little thing, this two-minute ad for a movie no one in the world besides James Franco would ever want to see. So, please, if anyone reading this ever actually saw The Sound and the Fury: is it a comedy or what? —MK

The Farrelly Brothers Award for most extensive use of bodily fluids in a movie: Hard to Be a God

Piss, shit, tears, blood, snot, sweat, spittle, spunk, phlegm, pus, vomit…did we miss any? —JA

Biggest Cop-Out: Mississippi Grind

Just because Ben Mendelsohn is overexposed doesn’t mean he can’t deliver the goods. In Mississippi Grind, the Australian actor adopts a flawlessly flat Midwestern accent to play a compulsive gambler on a cross-country bender. Appropriately for a film about high-stakes poker players, Mendelsohn’s performance is full of “tells” meant to alert us to the character’s fraying interior: his nervous, crumpled smile when things are getting out of hand is indelible. He gets so deeply inside the skin of a born loser that it’s a shame that the script insists on having him shed it in the end; as in their earlier Half Nelson, which hedged on its protagonist’s drug addiction, directors Anna Boden and Ryan Fleck insist on mining the scenario for redemption. In the process, they undermine Mendelsohn’s harrowing portrait of a man who always makes his own bad luck—the filmmaking equivalent of a suffering a bad beat on the river card. —AN

Most Welcome Absence: Matthew McConaughey

From going full moon in Magic Mike to full loon in True Detective, from slimming down to AIDS-weight for Dallas Buyers Club to headlining the latest overhyped Christopher Nolan film to pompously cruising America’s freeways in a succession of Lincoln town cars, the catchphrase-happy Oscar-winner had surely reached cultural saturation point over the past few years. So it was a relief that, with the brief exception of a Saturday Night Live hosting gig—featuring a truly bizarre monologue in which he narrated his early years, leading up to what he assured us was a mind-blowing Dazed and Confused audition—the Comeback (Now Go Away) Kid was mercifully absent from screens in 2015. No worries for those aching for a little more Matthew Mac, though, as 2016 promises to bring the long-delayed release of Gus Van Sant’s Cannes 2015 film maudit Sea of Trees . . . on whatever platform can bear its weighty themes. —MK

Didn't Think He Had It in Him: Jason Bateman, The Gift

There may not be a more limited comedy star in America than Jason Bateman, who has parlayed his TV resurrection into a one man-cottage industry, producing one thin, stale slice of milquetoast after another. And yet he’s excellent in Joel Edgerton’s not-uninteresting thriller The Gift, probably because this is the first time that a director has mined his boring normalcy for dread and resentment. Bateman’s Simon Callum—sounds like “Callow”—is a former high school alpha dog who gets terrorized by an old classmate (Edgerton) with an axe to grind; like nobody less than Daniel Auteil in Caché (an obvious inspiration), the actor shows how easily a front-runner can come unruffled, and how ugly his responses can be even in the midst of a wholly justifiable paranoia. In a year where Quentin Tarantino blew hatefulness up to epic proportions, Bateman’s performance is a true marvel of small-scale, everyday villainy. —AN

Least Helpful Publicist: Whoever Signed Me In to It Follows

Late from work, trapped on a stalled train, slowed down by a packed midtown street, I was thwarted in my attempts to get to a screening of the acclaimed horror film It Follows on time. Panting, sweating, and angry, I finally lurched my way to the screening room only to find that the door was closed and that the film had begun. No matter, the publicist shrugged and reassured: it’s only been on for a couple minutes and nothing much happens at the beginning. “I think you’ll get the gist,” he waved a hand nonchalantly. So in I went to watch the film, which began for me with an ambiguous scene set in an above-ground pool, and was a tense slow build from there. Diligent critic as I am, I eventually procured a screener to watch before reviewing the film to see this allegedly negligible opening I had missed. Lo and behold they were possibly the scariest, most explicit, and perhaps most essential minutes in the film, establishing the film’s central violent threat better than any scene to come. Lesson learned from this film and this experience: trust no one (especially ambivalent PR dudes). —MK

The Todd Solondz Memorial Don't-need-to-see-it-to-hate-

Ground Control to Major Tom: Tom Hardy

In this space last year, I waxed ecstatic about Tom Hardy's plangent performance in Locke, and hoped that it wouldn't end up as a footnote in a career that had to that point been defined mostly by a kind of high-flying stunt acting. To say that Hardy “broke through” in 2016 would be an understatement: he top-lined a globally high-grossing and extravagantly acclaimed blockbuster (Mad Max: Fury Road);won awards-groups plaudits (over here in Toronto) for impersonating both of the Kray twins in the UK hit Legend;earned a fawning essay by David Thomson in the pages of Sight & Sound; and has reaped his first Oscar nomination for The Revenant. It’s hard to remember the last time a star flexed so many sets of muscles—critical, commercial, abdominal—simultaneously. So why am I less bullish on this protean performer than I was 365 days ago? It may have something to do with the fact that great actors can make us feel proprietary, and that super-fandom is less fun in the shadow of consensus. But there’s also something increasingly mechanical about Hardy’s virtuosity. For starters, I wasn’t crazy about his work in Mad Max, which felt muffled, and not just because of the wrought-iron muzzle he sported for the first half hour; even if George Miller’s strategy was to de-emphasize his franchise hero in favor of Charlize Theron’s ferocious Furiosa, it was still strange to see Hardy become a passenger in his own star vehicle. That clearly wasn’t the case in Legend, a film that exists only as a showcase for a two-for-one-thespian special, and which is so bad on every level beyond (or more accurately below) Hardy’s performance that his effort feels somehow unbecoming. How can a guy this talented buy into such terrible material? His commitment is similarly evident in The Revenant, and while his work is physically and vocally impressive, it’s also perilously close to raw-throated self-parody: one can easily imagine Hardy’s nasty, half-scalped fur trapper Fitzgerald as a Batman antagonist. The point is not that Hardy should be more self-effacing. Locke was, after all, a one-man show. But if that film suggested that Hardy belonged in a noble lineage of technically proficient, emotionally acute, stage-trained Brits—from Ralph Richardson to John Hurt—then the choices he's made since indicate that he may already be too far gone as a mainstream movie star to do the kind of acting he's capable of. —AN

Paul Giamatti Award for Overacting: Ben Kingsley in The Walk

I don’t quite remember what Ben Kingsley was doing in The Walk, but my memory has convinced me that he makes his first appearance by riding in on a tricycle like Jigsaw from the Saw films. As imp/mime/cretin Philippe Petit’s French-Czech mentor “Papa Rudy,” the man who encouraged the clearly deranged dream-following of your hero (because he ain’t my hero), Kingsley adds another notch to the bedpost charting how many times he fucks his own career. Runner up: Paul Giamatti in Love and Mercy. —MK

Jaume Collet-Serra Award for Achievement in Films Directed by Jaume Collet-Serra: Run All Night

This one is becoming a bit predictable, I admit, but as long as this Reverse Shot–approved auteur keeps getting gigs directing mid-level studio thrillers, it’s our job to monitor his progress. Last year, the report was middling, at least from where I was sitting: my colleague and fellow JCS booster Nick Pinkerton liked Non-Stop more than I did. There, the problem was the mid-air collision between a gifted action director and an intractable, gimmicky dramatic scenario that seemed to stall his momentum; the eloquent camera movements felt wasted on a story that went nowhere. By contrast, Run All Night is, as its title suggests, all momentum, and at its best, it propels itself past—if not above—the clichés of its screenplay. As Liam Neeson shepherds son Joel Kinnaman through a New York night with assassins in every shadow—agents of retribution sent by gangster Ed Harris, who lost his own heir a few hours earlier—Collet-Serra blends old-school chops (a foot chase around Madison Square Garden at the end of a Rangers game) with some wacky, over-amped nonsense (a heavily artillerized SWAT siege of an apartment block) and, crucially, never inflates the story beyond its narrow parameters. In lieu of the wryly malevolent, genre-commenting comedy of Orphan or the stealth expressionism of Unknown, Run All Night serves up steadily straight-ahead stuff, and while it’d be nice to think that Collet-Serra is eventually going to get somewhere, his current velocity has him ahead of a pack that hasn’t yet yielded another dark horse. —AN

The Golden Torso Awards

It was a good year for male movie stars with improbably chiseled torsos. From the tattooed vision of Nick Cannon’s title character in Chi-Raq; to the World’s Most Preposterously Gorgeous Hacker played by Chris Hemsworth in Blackhat; to the ungodly gods of Magic Mike XXL (with special mention to Joe Manganiello, for whom it is actually illegal to wear a shirt); to the ne plus ultra of fitness, Creed’s frighteningly sculpted Michael B. Jordan, who clearly hadn’t eaten a fifth of a French fry for a year before stepping into the ring, there was a lot to look at. Lest you think this is just a catalog of eye candy, however, all this grade-A beef on display left me thinking seriously about the comparative lack of the female form on display in mainstream movies. Perhaps the pendulum has finally begun to swing in the opposite direction. —MK

Best Documentaries Not Nominated for the Academy Award: Songs from the North, Because I Am a Painter, Of Men and War, Heart of a Dog, The Pearl Button, We Come as Friends and . . . Reverse Shot’s #1 film of 2015, In Jackson Heights (!)

Least Necessary Movie: Black Mass

There might’ve been an interesting movie to be made about the sixteen years gang boss James “Whitey” Bulger spent as a fugitive from the FBI. His settling into the mundane business of ordinary life (with the occasional geographical pivot to avoid detection) well outside of his Boston comfort zone could have been the wise-guy flipside to Bill Condon’s pleasant, seemingly forgotten Mr. Holmes, about Sherlock in his rural twilight years, or an extended version of Ray Liotta bending over for the newspaper in suburbia at the tail end of Goodfellas. Instead, we got Black Mass. Remember The Departed, whose Frank Costello character, played by Jack Nicholson, was partially based on Bulger? Drain all of the humor, surprise, acting charisma, and visual dynamism out of that and you have Scott Cooper’s drearily unnecessary return to the mean streets of “Southie,” that location beloved by producers who cynically want their crime pictures safely white enough to play in conservative markets. Screenwriters Mark Mallouk and Englishman Jez Butterworth (yep), focusing on Bulger’s criminal years and collusion with the FBI, write dialogue as if they sliced up a bunch of boilerplate gangster movie scripts, put the scraps in a hopper, and blindly grabbed. Johnny Depp, whose commitment to the part of Bulger doesn’t go beyond his absurd blue contacts, delivers go-nowhere tough guy speeches when he isn’t machine-gunning Peter Sarsgaard in a daylit parking lot, but as a corrupt cop, it’s Joel Edgerton who gets to say things like, “We’re in too deep and he knows it!” and “The streets taught me that you give and you get loyalty from your friends . . . and loyalty means a lot to me.” Awkward references to local sports teams and landmarks attempt to lend Black Mass a veneer of authenticity, but Cooper and Co.’s phony dullness makes one long for even the modest genre intrigue of something like Broken City. —JS

Here We Go Again Award: Guillermo del Toro

The first half of Guillermo del Toro’s lusciously ornate Gothic romance, with its Brontë meets Doyle intrigue, appealingly old-fashioned waif-like performance by Mia Wasikowska as the haunted wannabe-novelist daughter of a self-made magnate, and over-the-top period (but what period?) shoulder pads, has such a strong sense of classical storytelling and traditional Hollywood showmanship that I felt I had finally found my way in to the horror auteur’s oft airless world. Turns out it was just a pretense for more del Toro doodads. Once our stricken heroine’s father’s head is smashed over and over into a porcelain sink until his face cracks open and his brains and skull spew all over a bathroom floor, Del Toro lets loose and shows his true, deep-red colors. Sure, Jessica Chastain is having fun as the villainous, incestuous sister-in-law (telegraphed from scene one because anyone who dressed in black and plays a somber piano must be evil), but del Toro is so busy putting her and everyone else through their tired paces that nothing feels like it’s developing in any natural way. Del Toro’s creepy-crawly characters often feel less like natural outgrowths of their stories than wax figures just biding their time until they get invitations to the Mad Monster Party of the director’s mind. —MK

Best Last Shot: 45 Years

Worst Last Shot: Mommy

Worst Edit: Infinitely Polar Bear

Perhaps it’s been recut since, yet I remain haunted by a moment during a press screening of Maya Forbes’s overly audience-courting bit of adorable autobiography, starring Mark Ruffalo as a bipolar dad trying to keep himself and his family together as he shifts between completely unconvincing, unthreatening tonal registers. The film has mostly evaporated from memory; but a moment has stayed with me: at one point the film cuts from a scene directly on a point when Ruffalo starts a new sentence. So there was just a blip of the actor’s voice as he began speaking, abruptly cut off. Then a new scene begins. I would think what I saw was a work print, but it had already premiered to fanfare at Sundance many months earlier. If the film were not such a stylistic grab bag, chock a block with hideous cinematography and amateurish kid performances seemingly patched together in post, perhaps I would have shrugged it off as an honest mistake. Unfortunately it seemed to fit right in to the rest of the film. (I am more than happy to revise this observation, although it would necessitate seeing Infinitely Polar Bear again.) —MK

Ten Movies You Need to See That Didn’t Make Our Ten Best: Amour fou, Bridge of Spies, Chi-Raq, Creed, Heaven Knows What, Irrational Man, Phoenix, Saint Laurent, La Sapienza, The Wonders

Hardest to Discuss in Brief: Out 1

Julien Allen: What should we do for Out 1? How does one do 300 words on this extraordinary behemoth? I have thought of half a dozen things, all unsatisfactory:

Biggest Film

Best Whodunit

Hottest Cast

Best Box Set

The Michael Lonsdale Award for Most Eyebrows

Most Alcoholic Screening

Jeff Reichert: Most Masculine Movie Experience: Out 1. “Hey Bra, I'm watching Out 1 today. All of it. Ya feel me?”

JA: “Oh mate, I hoped they’d do it all in one sitting but some poofter complained he needed a piss break so they broke it up. Denied.”

JR: Though I’m sure RS readers would love us to go on at length just like this, I guess we could try to talk about the movie?

JA: Er, yeah, of course. So . . . it’s a film about collaboration, right? That word has some pretty dreadful connotations in French, but this film is trying to rediscover the idea of collaboration, in art and life, with all its intoxications and pitfalls.

JR: Though it might be more pitfalls . . . I will say that making one’s way through Out 1 at BAM over a few days felt like a collaborative effort, with various groups in the audience clearly forming their own viewing teams, debating during the breaks, planning meals together and the like.

JA: Most of the collaboration we see (the theatre, the “Treize”) is clearly enriching, but oh so finite. I wonder the extent to which the hallowed Treize is based on Rivette's experience with the Cahiers founders, some of whom he cast (Doniol-Valcroze, Rohmer). Our own collaboration at the Prince Charles Cinema in London was all too finite—over in one weekend. I wanted to turn up on Monday morning with the others and keep going.

JR: I also felt like diving right back in as soon as it ended, even though there were more than a few times during those punishing rehearsal sequences where I wanted to crawl out of my skin. Especially that one with the actors putting their feet all over each other.

JA: Those freeform Grotowskiite improv sequences carried a weird suspense: a) for how many more hours can the film legitimately keep this up? and b) how much more certifiable will the rehearsals get before they stop? I love how the breaking point is the theft of cold, hard money. Here’s a post-’68 story about people opting out of all the expected norms. But when they get out into the street, looking for cash, all of a sudden they look pretty lost.

JR: Well, it puts all of ’68 into relief, doesn’t it? Instead of merely valorizing that moment, Rivette’s shown that there was also a naiveté, a blinkered quality, a dilettantism existing alongside more noble commitments. It occurs to me while writing this that the same could be said for anyone who attempts watching a film like this. How can we afford such a lifestyle to watch 13 hours of a movie in a week?

JA: Many of us were seduced by the retro-cool prospect of stepping “off the grid” when civilians rightly thought we were a bit unhinged. I wonder how many civilians have binge-watched twelve episodes of House of Cards though? At least Out 1 was screened during the daytime, with sensible breaks in play to try and unpack what we were seeing.

JR: I did a bit of a split: two long evenings and then gave over pretty much the entirety of my Sunday to the film. Especially with those hilarious B&W “last week on Out 1” intro sections, it certainly felt like binge-watching TV. The main difference being that Rivette’s narrative doesn't really begin until four hours of the work has elapsed, where most TV series need to lay out a bunch of elements upfront to keep viewers hooked.

JA: A lot of the Prince Charles “equipage” found ourselves drawn into Out 1 with an intensity that matched a cliff-hanging serial, despite Rivette’s narrative approach being so wholly antithetical. Was it the sense of history, the peculiarity, softened by New Wave familiarity? (In case we’re reaching the end of the road, I’d like to point out that a young woman behind me curled up into a ball and slept through Chapter 3: a perfectly legitimate thing to do.)

JR: I’m well known within the RS team for taking an occasional in-movie snooze, but thanks to regular over-caffeination, I managed to keep my wits about me through the entirety of the run. But I wouldn't begrudge anyone a nap. And I don’t know that Rivette would either.

JA: If I was going to curl up inside a film, I'd be pretty happy for it to be this. Some of the best stories of our lives were designed to send us to sleep, after all.

JR: Zzzzzz. (Maybe this is our exit?)

JA: Perfect. Well that's 3000 words. Anything we can use?

JR: Why don’t you give it a first pass.

[Time elapses]

JA: I have it down to 850, and it’s actually quite ok.

JR: Collaboration! NOW TOUCH YOUR FEET TO MY FACE FOR TWENTY MINUTES.

JA: :(