The twenty best films of the decade were determined by polling all the major and continuing contributors to Reverse Shot in the publication's history.

The Beyond

Michael Koresky on The Tree of Life

Some works of art feel too grand to fully make sense of in the context of one’s life. Writing about them can be one way of trying to make them fit properly. Art that is truly meaningful to us—aesthetically daring, overwhelming work that pushes its given medium into new places, but which also strikes us on some kind of irreducible, indefinable personal level—is never truly complete. It lives on in our minds, where it keeps changing, shifting, haunting, absorbing life experiences that are beyond its own capacities and that its makers never could have known or intended.

Even for those of us who immediately loved Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life, there was something almost embarrassing about how overwhelming—how ambitious, all-encompassing, and unabashedly engaged in existential ideas—it was; it seemed as though the combination of its extraordinary scope, the surprising accessibility of its meaning, and its daring reconception of mainstream cinematic vernacular could only result in something painfully overreaching. The Tree of Life was early on compared to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey for its wildly expansive, origin-of-the-species time-hopping experiments, but it doesn’t even have that film’s rich core of irony to help steel its adorers against all comers. Malick’s movie is instead dead earnest. The Tree of Life, now, almost ten years since its premiere, may still feel like a monolith casting a shadow over a decade of film culture, but the experience of watching it remains as excitingly intimate and earthbound as it ever was, tiny, precious. There’s no Star Child here, just one small life that exists in a continuum with all others, a reminder of all eventualities. It’s a film that poses questions rather than gives answers; like any kind of spiritual belief system, it relies on the emotional engagement of its participants—in this case, viewers—for its inquiries to register as wisdom.

All movies change as we age, though The Tree of Life in particular has never stopped changing since its release. The film has gone on to encompass various forms, including three different versions of his 2016 nature “documentary” Voyage of Time, all constructed partly of footage originally conceived for The Tree of Life’s “creation of the universe” sequence. Voyage of Time, still only available in occasional theatrical or large-format screenings, indicated that Malick hasn’t gotten his long-gestating passion project out of his system. Then, in 2018, Malick released an entirely new extended cut of The Tree of Life on The Criterion Collection, a version that essentially alters the internal rhythms and narrative expanses of the film, and in its very conception expresses Malick’s fascination with the possibilities of digital editing to create alternate realities from untold stockpiles of material. The three films that the once reclusive, unprolific Malick made in shockingly quick succession after The Tree of Life—To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups (2015), and Song to Song (2016)—similarly stand as testaments to the revivifying experimentation of this now late seventy-something filmmaker: each film gives the feeling that at least fifty other films could have been knit together from what was captured on camera.

The name Terrence Malick has come to mean something quite different in just the past ten years, and certainly since To the Wonder’s release. To supporters, he's an indefatigably experimental filmmaker pushing at the limits of cinematic narrative form; to detractors a maddeningly undisciplined camera-carouser who’s making movies like he’s running out of time. In the five decades leading up to the release of The Tree of Life, he had been more commonly thought of as a notorious if lovable perfectionist whose concerns about form and meaning, and his inquiries as a student of philosophy (he studied with Stanley Cavell at Harvard and published a translation of Heidegger’s The Essence of Reasons that is considered authoritative), superseded his need to crank out movies, resulting in a largely reverent cinephile public desperate for the next film, which he had somehow convinced a major Hollywood studio to finance. His most recent film, last year’s A Hidden Life—his fifth this decade—was made independently, in Europe, with no name actors. When The Tree of Life was released, this version of Malick would be unimaginable. He was coming off of The New World (2005), a film that many of us found indescribably beautiful and moving, but which, in its general fidelity to linear—if expansive—historical time, didn’t quite hint at the storytelling experiments that would overtake and further his aesthetic. The Tree of Life comes at us in a rush of fragments, not because that approach approximates how we experience the world on a day-to-day basis, but because it feels like how our minds and memories try to make sense of it. Malick’s filmmaking, especially here and in everything after, strikes me as a way of using the cinematic form to piece together a visual approximation of a world made unknowable by our own perceptions, our own human limitations.

*****

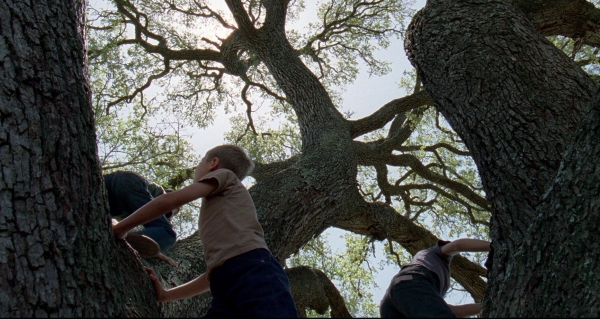

Malick and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s radical approach to image-making in The Tree of Life—to cache a vast array of naturalistic yet impressionistic images, tightly following actors with lenses of short focal length as they move through space and, through their sheer physicality and emotional presence, create variations on themes, later to be complemented by ethereal, disconnected voiceover—recontextualizes moments that in other films would hit familiar beats. It's an approach they would continue to experiment with over the next three films. Through this, narrative consequence is implied rather than stated, forging connections between images that somehow create harmony through discontinuity, a method that might have more in common with cubism than traditional linear storytelling.

Despite being made up of fragments, there is a grand design and a clear shape to The Tree of Life. It's a film constructed of discrete, symphonic movements. The first is an introductory prelude that establishes, via voiceover and the achingly beautiful choral melancholy of John Tavener’s “Funeral Canticle,” the film’s central theological dichotomy—the split between the “way of grace” and the “way of nature,” the former reflecting the human attempt to control the latter by sheer force of will and love. Following the initial instance of the recurring image of an abstracted halo of light floating against a black background—an effect that manages to convey benevolence and grace without inferring the existence of a “higher power”—the film’s first shot presents a little girl looking out a barn window at a bucolic landscape. We hear the voice of Jessica Chastain on the soundtrack, smoothly folded into Tavener: “Grace doesn’t try to please itself… accepts insults and injuries,” while “nature only wants to please itself.” We can assume this child to have been Chastain’s character as a child, a picture of innocence, an idyll of uncorrupted grace. Her goodness presides over the entire film, not as an idealized vision of feminine forbearance, but as a symbol of the human pursuance of grace despite suffering, as she will experience unimaginable loss, the kind to shake anyone’s faith. She whispers to God, “I will be true to you, whatever comes.”

It has come. After a cut to black, a telegram is delivered. In a sequence that registers as no less devastating for us not yet knowing the characters, a middle-aged wife and husband, Mrs. and Mr. O’Brien, played by Chastain and Brad Pitt, discover that their 19-year-old son has died. We are not told the circumstances; we only get snatches of information, shards of sound. Everything about the scene—which takes place in a house we will not see again for the rest of the film—is alienating. The suburban street on which Mrs. O’Brien tearfully grieves, shuffling back and forth and attracting the attention of neighbors, has an almost surreal feel, an unfair beauty that seems cruel in contrast to what she is going through. Friends provide unhelpful attempts at words of anger or comfort (“He sends flies to wounds that He should heal”; “Life goes on”). The looming oak trees, gloomy setting sun, persistent breeze are terrifyingly remorseless. At one point as the camera drifts through leaves and branches, we hear the muffled, off-screen sound of Mrs. O’Brien’s agonized shrieking. This sequence establishes the film’s narrative engine: the memory of a death in a family, and its emotional repercussions across time.

Malick jumps forward to a brief passage, set in a sleek, contemporary urban jungle of glass buildings—the first time any part of a Malick film was situated in the present day. We might infer that what we’ve seen so far have been the considerations and memories of a middle-aged man, Jack (Sean Penn). Foggy in reverie, Jack is remembering his younger brother from decades earlier, and we can ascertain from various details—a curt phone call with his father; a memorial rite with his wife—that today is the anniversary of his death. (Malick’s younger brother died in the late sixties, it is believed from suicide.) As we will return to this place and time later in the film, we come to understand that the entirety of The Tree of Life takes place on this day, a subjective expression of Jack’s interior state, of how death functions in one’s life as a companion, our lost ones as structuring absences. “How did she bear it?” Jack wonders, in voiceover, about his mother, as though addressing himself. Malick brings us back to Mrs. O’Brien, who has her own questions as she wanders that desolate suburban street bathed in the glow of the late-afternoon sun: “Lord, why? Where were you?”

Her words recall the film’s opening epigraph: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? . . . When the morning stars sang together, and all the sons of God shouted for joy?” As in the Book of Job, such questions can only be answered with questions. Chastain’s beseeching triggers the film’s unapologetically operatic creation sequence, a cosmic response to questions unanswerable in words. A reminder that Malick is indeed a great showman as much as a cinematic philosopher, he overwhelms the viewer with sound and image, swirling chemical admixtures, floating organisms, and galactic formations meant to indicate the beginnings of the universe. If these mysterious organic effects, creating approximations of exploding supernovas and gaseous penumbras, brought about using liquids, cloud tanks, sheets of glass, and images caught at extraordinarily high frame rates, remind one of the tactile effects of Kubrick’s 2001, that probably has much to do with the fact that Malick hired that film’s legendary photographic effects supervisor, Douglas Trumbull, as a consultant. Malick punctuates these unexpected, grand, ethereal images with dramatic cuts to black, and sets them to Zbigniew Preisner’s modern operatic composition “Lacrimosa.” Originally written in eulogy for the composer's friend, filmmaker Krzysztof Kieslowski, the plangent “Lacrimosa” is expressive of the overall tenor of Malick’s project: a song of death accompanying images of the ultimate birth, an expression that the earth has been in a process of mourning since its very creation.

*****

As Malick shuttles the viewer ahead billions of years, through the first indications of amoebae, fish, and lizards, he briefly pauses on a moment that has proven divisive—and therefore is probably one of the film’s defining images. A majestic Plesiosaur, its mammoth body sprawled across a desolate evening beach, cranes its long neck to look at an enormous, bleeding gash on the side of its torso. After pondering the wound, the solitary beast looks back out at the unresponsive, unforgiving waves. In the next cut, we see a brief low angle, up from the depths of the ocean, at silhouettes of swarming hammerhead sharks; perhaps one of them is to blame for the dinosaur’s condition, though Malick doesn’t seem interested in constructing cause-and-effect narratives as much as historical and biological leaps and associations. The mortally injured Plesiosaur is an image of poignant majesty, but it’s also provocatively ambiguous: is Malick telling us that the sentient animal is aware of its own imminent death, or is this just a description of the dog-eat-dog way of nature? If it’s the former, are we meant to feel sympathy for the creature, simply because of its consciousness? I suspect so, but more importantly, I also think that this scene, no longer than fifteen seconds, is among the film’s most emotionally crucial: if as a viewer you are not moved by it or reject its basic principle—that all earthly beings, since time immemorial, are empathically connected by our facing of the inevitable—then The Tree of Life might not function at all. In this marvelously confrontational moment, Malick does something very few American filmmakers would dare do: he risks ridicule.

Often when I read contemporary reviews of Malick, I recall the 1851 London Literary Gazette review that called Moby Dick “wantonly eccentric, outrageously bombastic” and then took Melville to task: “Most careful, therefore, should he be to maintain the fame he so rapidly acquired.” Such a sentiment is typical of how the public tends to treat its great artists in the moment, before time and reason become powerful enough to bury the avalanche of bad—and bad-faith—takes.

The Tree of Life was by no means met with a cacophony of negativity upon its release in the spring of 2011, but it wasn’t wholly admired either. One might be amused, years later, to note that even the most venerated critics groups in New York and Los Angeles voted such lightweight offerings as The Artist and The Descendants, respectively, as their best pictures of the year—films that risk nothing and which court approval at every turn. The lingering distrust and suspicion with which some treat The Tree of Life extends from the fact that it augured the widely unpopular radicalization of Malick’s form. His subsequent output has evinced a disinterest in playing by the rules, offering experimentations that dissolve the boundaries we normally see between captured and constructed life in narrative cinema. As a result, he’s become the most mocked and chastised of major American film artists. Reviews have seemed increasingly like the on-high finger wagging of taskmasters. But of course critics too often act like hall monitors rather than humans who have tasked themselves with the act of wrestling with art, making it seem like the artist should be serving at our pleasure. More careful should he be…

*****

After the origin sequence, which concludes with the image of a meteor silently penetrating the earth from a great, placid distance, Malick begins another, revelatory sequence of creation: Mrs. O’Brien giving birth to her first child, Jack, and setting in motion the film’s narrative proper, an impressionistic domestic drama about a Christian family in fifties Texas that takes up most of the running time (and even more so in the extended cut of the film). Though Malick is finally, officially situating us in the suburban Texas home of his main characters, his approach remains anything but straightforward, racing through the family’s early years with little Jack, and then his two younger brothers. In quick, offhanded scenes, we see milestones in human consciousness. A toddler experiences his new baby brother with fascination, skepticism, and resentment; that same child soon discovers control and ownership, exclaiming, “It’s mine!” after absconding with a piece of cake. Moments of childlike awe, captured with documentary naturalism, are mixed up with images of a more fanciful, expressionistic nature: a child swimming through an ocean-drowned bedroom; a kitchen chair suddenly moving by itself as though by some invisible poltergeist. The Tree of Life is defined by these kinds of negotiations, between the immanent and transcendent worlds, between the known and unknown, the earthbound fears and the wish fulfillment of dreams. There’s only so much that Mrs. O’Brien can do to stave off her children’s loss of innocence—we see her early on shielding little Jack’s eyes from a neighbor having an epileptic fit on her lawn. Nature inevitably will overtake grace.

“You see this line? Do not cross it,” Mr. O’Brien instructs little Jack, using a stick to outline the invisible boundary separating their lawn from their neighbor’s. This brief lesson in property ownership is itself a kind of loss of innocence, an unmistakable imparting of value over land. This moment triggers the first strains of Bedřich Smetana’s grand “The Moldau” on the soundtrack, the most recognizable movement of the Czech composer’s symphonic, nationalistic cycle titled My Homeland, or Má vlast. At the moment that the piece ascends to its first, soaring crescendo, however, Jack receives a different lesson, this time from his mother, who holds and twirls him in their yard at magic hour before stopping, pointing at a patch of sky and proclaiming “That’s where God lives.” Neither lesson is verifiable, but each is bred of conviction: this is where we live, father affirms, so stay within these bounds; that is where God lives, mother says, so aspire to that. Father is telling Jack not to transgress, mother is implying that he can transcend. Meanwhile, “The Moldau” cascades through time, accompanying a breathless catalogue of experiences and in-between moments that take us up through the three boys’ adolescence.

From this point, the film centers mostly and vividly on the experiences, witnessing, and moral confusions of preteen Jack, played by an extraordinarily unaffected Hunter McCracken, whose singular presence is magnified by the fact that he has never acted in another film. With his jutting ears, perpetual scowl, and head eternally cocked to the side, Jack has the mien and bearing of a born skeptic. Essentially good yet fearing his capability of evil, Jack is caught between the warring emotional and philosophical factions represented by his gracefully nurturing mother on one hand and his naturally insecure, overbearing father on the other. He begins to test the limits of his world, to transgress its firmly set boundaries: breaking into his neighbor’s house and stealing a woman’s slip, taking part with other boys in the mutilation of a frog, shooting at his little brother’s index finger with a BB rifle. He’s intentionally straying from the path of righteousness, so clearly taught to him in church sermons, but he’s also exacting spiritual vengeance on his father, whom he has increasingly grown to resent, even hate. “Please God kill him. Let him die. Get him outta here,” Jack whispers in voiceover at one point while gazing at him, desperate for his father’s love, hoping for his father’s disappearance.

*****

Just four months after I first saw Malick’s film, my father died. Five months after that, I got married. All this is to say that less than one year after I saw The Tree of Life for the first time, I was no longer the same person. Or at least I no longer felt like the same person, like I was suddenly made up of different parts, some regenerated, some lost forever. By the end of the first year of its release, I had seen The Tree of Life seven times in the theater. I had to keep returning to it, as though it was providing an emotional sustenance I needed at a time when the world didn’t seem to make much sense. To this sensitive, secular mind, Malick’s ultimately nondenominational spirituality was almost too-perfectly timed, as though he were speaking directly to me through the medium that has brought me closer to the sublime than any other.

The questions about the universe and our place in it that Malick was posing didn’t seem, as some of its detractors claimed, overly ambitious or foolish or the dreaded p-word pretentious, but rather fairly basic, in the best possible way: why do people go through so much pain, and how can they stand it? Born out of the same Jobian theological tradition as the Coen Brothers’ A Serious Man, which at the time was still ringing in my ears—and teeth—Malick’s film was less caustic and offered the right amount of nurturing. To put it broadly and bluntly, The Tree of Life, a film derided in some circles for what was perceived as Christian imagery (especially in its final passage, which for some bordered on kitsch), appealed to me as an atheist: it somehow allowed me to experience a transcendence I needed to feel. It was a prayer for someone who didn’t know who to pray to, a kaddish for a son who never learned Hebrew.

When the film reaches its entirely symbolic final movement, a journey to “the end of time,” as Jack sees it, it’s become purely epiphanic. On an eternal beach, the living and the dead, the young and the old, the human and the angelic, the present and the past are united, not in reality but in revelation, in wisdom, in an acknowledgment of what we cannot know. The Tree of Life stirs belief. It’s a world where every shot is equally potent because every image contains birth and death, love and fear in equal measure. An image of a field of sunflowers is freighted with as much inherent power and meaning as a low-angle of a glistening high rise or an ominous flock of birds or a child playing with a dinosaur toy or a mother floating fantastically in midair.

Malick’s film manages to exist in all these spaces, allowing us to connect the everyday to the cosmic in a way that neither minimizes human experience nor places us in a position of superiority. I cannot tell if The Tree of Life makes me feel elation or dread, catharsis or sadness, awe or empathy—probably all of the above, coming in waves. It’s a film that, even in its oddness, feels familiar, as though it’s always been a part of us, like grief itself. Lacrimosa. Through birth comes death; through death comes wisdom. In the time we have between, we ask questions.