Dancer in the Light

Michael Joshua Rowin on Robert Altman’s The Company

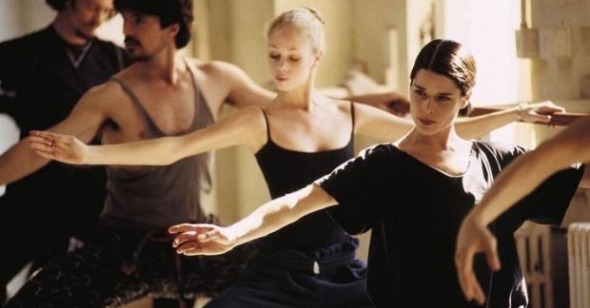

Usually considered “minor” Altman, an antinarrative whatsit—part document, part ballet recital, part realization of Neve Campbell’s lifelong dancing aspirations—and situated unadvantageously between return-to-form Gosford Park and career capper A Prairie Home Companion, Robert Altman’s The Company is probably not the first film people recall when they think of the digital revolution and the myriad new cinematic possibilities it presents. Superficially it looks and feels not very much different from any number of other Altman ensemble pieces punctuated by stirring artistic performances like Nashville and Kansas City, but free from the political, social, and racial tension fueling those films, its stakes are substantially lower. “What’s new here that he hasn’t done before?” the inattentive viewer will ask, and that’s where the misunderstandings of The Company begin.

Though a beneficiary of digital technology, The Company never announces itself as such. The 2003 film is modesty itself, not allowing its own art to take the spotlight off the Joffrey Ballet dancers who are, after all, the story and spectacle. It’s quite likely that most viewers aren’t aware that if it hadn’t been shot on hi-def digital video (virtually indistinguishable from traditional film stocks) The Company couldn’t exist, though to judge by the film’s reception that piece of information might only elicit a polite shrug. The ability of several light, cheap, digital cameras to record performances for extended periods of time, with the possibility of quick retakes is absolutely essential for shooting dancers physically prohibited from waiting around and cooling off while a crew reloads for another run. And yet Altman refuses in any way to demonstrate or call attention to this process.

An irony, because for Altman process matters far more than product: his well-known modus operandi is to merge actors and nonactors, directing them in the same manner, using long shots to capture spontaneous interactions and mistakes, and often staying with caught-off-guard moments that get at a character or scene’s essence better than adherence to a strictly interpreted script could. It’s not that the final results are incidental, but that creativity lies in the risks it takes in getting there. Viewers can see the Altman process on screen, but as if asking his audience to keep the method in mind he’ll frequently open his films with a performance that is soon interrupted so its inner workings are revealed. The Company works in this vein minus the illusion- and convention-shattering jolts of Buffalo Bill and the Indians or Nashville. It might very well be called a “mellow drama”—Altman shoots The Company with a grace and lightness befitting its subject matter, allowing the Joffrey’s rehearsals, board meetings, and costume changes to unfold as naturally as a perfect pirouette.

Instead of contributing to overarching plotlines, generic contrivances and clichés are turned into slight detours emphasized as much as, or often less than, the exclusive peeks into the mechanics of ballet that constitute the heart of the film. Campbell’s character, Ry, for instance, inevitably substitutes for an injured lead just before the show, but the event is gotten out of the way at the very beginning of the film. Producer and star Campbell already democratically integrated with the other dancers, the driving storyline becomes the company, a company that must go through an intense, dedicated process to achieve the film’s centerpiece performances. Almost imperceptibly, the film becomes its own metaphor.

It’s not just the rehearsals and shows—expertly executed, filmed, and cut—that would be possible to watch without having been shot on HD. There’s also a terrific scene, a Joffrey Christmas roast in which dancers dress up as their teachers and mock their own routines, that was shot similarly—Altman claimed having shot with four cameras rolling for at least 25 straight minutes. And yet on first glance there’s no reason to think we’re watching anything achieved so differently than the loose jamming of Nashville and Kansas City, the controlled chaos of A Wedding and Gosford Park. What makes The Company significant as a digital film, then, is that for all its emphasis on process and behind-the-scenes intimacy its format has allowed a director to apply his honed cinematic treatment to subject matter he couldn’t otherwise approach.

Before his recent death Altman stood apart from a small but trailblazing contingent of older generation filmmakers—Godard, Coppola, Lynch—now moving into the digital age and expanding their art through it. An apples and oranges comparison, perhaps, but one that proves consistent simplicity, even across the technological divide, can often be as rewarding as radical change, and that the advantages of a new toy can be determined as much by the subtle uses to which it is put as by audacious ones. If we don’t herald or appreciate The Company as a revelation on the same level of In Praise of Love or Inland Empire it’s because the film’s innovation is so much absorbed into the process of the filmmaking that we can’t immediately know its technical import. But that process is the secret treasure which when once discovered makes us fully appreciate just what a miracle—a minor one perhaps, but a miracle—it really is.