Surface Tensions

Vicente Rodriguez-Ortega on L.I.E. and Firstborn

Forget about the clumsy and poorly executed chase scenes, the hideous worst-of-the-eighties synth-rock soundtrack, and the clichéd ending in which the nuclear family stands triumphant and intact inside their suburban paradise (or cage)—Michael Apted’s now largely forgotten 1984 Paramount Pictures melodrama Firstborn is, above all, a conservative Reagan-era tale. The paranoia of previous decades about the infiltration of external forces into the social fabric now took place in the realm of the picket fence and driveway. It anticipates a cycle of movies in the early 1990s, such as John Schlesinger’s Pacific Heights or Curtis Hanson’s The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, which suggested that good Americans are never safe. It may be your nanny or your tenant, or, like in Firstborn, your mother’s new boyfriend, but someone will threaten the wholesomeness of the family one way or another. If in the 1970s and early 1980s it was time for America to heal its wounds with action and violence-driven products such as the Rambo and Death Wish series and, within the horror arena, the suburb was under siege by psychologically perverse creatures that came from the outside world to contaminate and menace it (The Last House on the Left, Halloween, or A Nightmare on Elm Street, to name just a few), in the 1990s any fellow American—male or female—could come in and shred the domestic paradise of the middle class to pieces.

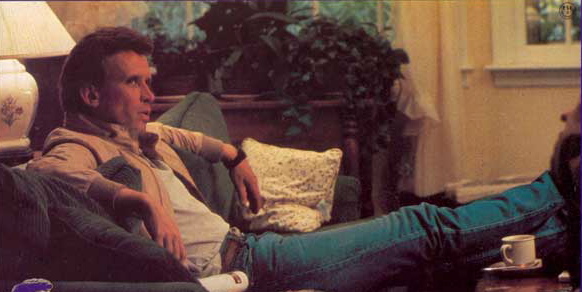

British-born Michael Apted had garnered a solid reputation as a documentary filmmaker with the first installments of his Up series. However, by the time he made Firstborn his career had turned towards the mainstream with such features as Coal Miner’s Daughter, a biopic of Loretta Lynn starring Sissy Spacek, and Gorky Park, a thriller set in the former U.S.S.R starring William Hurt, Lee Marvin, and Brian Dennehy. Firstborn has a simple template: Wendy (Teri Garr), a single mother of two boys (Christopher Collet and Corey Haim), longs for a man; at the same time her oldest son, Jake, has just turned sixteen and is becoming a man himself. It begins as a flat drama, and then it shifts into thriller mode with the arrival of Wendy’s new boyfriend, Sam (Peter Weller), who brings not only a sexual appetite but also a bunch of empty promises about building a family together. In fact, Sam is an alcoholic slob who sits around watching TV; he literally contaminates her (with drugs) and tries to do the same to her children. In the words of Jake, suspicious of Sam’s presence, he is nothing but “a loser and a deadbeat.” His unkempt look and his swear-filled tirades situate him outside the polite, educated world he enters. He soon turns violent when Jake confronts him and attempts to show his blind mother who her new lover truly is. On top of this, of course, he is a pothead and coke dealer, and thus belongs to a dangerous class that brings addiction and criminal behavior to an honest, benign world not properly equipped to confront such a menace.

At the end the two sons and the mother join forces, using violence (with the help of a baseball bat, no less) to scare Sam off. Jake has accelerated to adulthood’s finish line, and can take care of his mother, in every way other than sexually. In the closing shot, as the two sons and mother look out the window, the camera pulls away (the wooden frame of the window resembling the shape of a jail cell); the faces of the film’s protagonists become less visible and the narrative acquires an abstract tone, implying that we have just seen one of many stories, one that tries to capture a widespread social crisis. Here, perhaps Apted means to appropriate Douglas Sirk’s signature ironic closing statements from All That Heaven Allows or Written on the Wind. Or, perhaps, looked at differently, the film is saying that no matter what difficulties it faces, no matter how many Sams there are, constantly looming and ready to exploit and corrupt it, the family shall conquer.

Suburbia gets a seemingly different representation in Michael Cuesta’s 2001 independent drama L.I.E., which starts with 15-year-old Howie (Paul Dano) considering committing suicide by throwing himself from a bridge onto the Long Island expressway. Immediately after, Howie’s voiceover tells us about the deaths of famous people on the highway, including his mother. Soon we find out that Howie and his friends are fornicating teenagers, breaking into people’s houses and watching their parents fucking their partners in the ass. Howie also likes to play with lipstick. And here is where Big John Harrigan (played by the magnificent Brian Cox) enters the equation. After Howie and his partner in crime, Gary (Billy Kay) try to burglarize the old man’s home, Howie begins to develop a friendship with Big John, a known pedophile who, in a clichéd touch, gets aroused by Walt Whitman’s verses. As Howie’s sexual identity continues to gravitate towards homosexuality through the looks, gestures, and compliments of Gary, and his developing (even if only platonic) relationship with Big John, Cuesta seems to aim at offering a glimpse into a society corrupted not by violence but because love is not allowed to flourish within it. His calibration, though, is off, and L.I.E. stops short of diagnosing the real causes behind the pervading social sickness it initially sketches.

As his abusive father turns his attention to a looming FBI indictment, Howie dreams of running away to California with Gary, far from the perverted milieu that surrounds him. Cuesta’s twist is that the perversion does not come from the pedophile—in contemporary society typically considered the bottom of humanity’s barrel—but from everything else that fuels the rhythms and realities of the Long Island youth. The film relies mostly on Cox’s unpleasant charm and Dano’s well-played naiveté. As the bond between Harrigan and Howie grows tighter, the former starts taking a paternal role: giving the teenager his first shave, consoling him over his father’s detention, and tucking him in at night. In the end, a former teenage lover shoots Harrigan to death and the social wound is closed and healed. The film does make the remarkable effort to humanize this pedophile, but he is ultimately viewed as better off dead, for his own sake and ours. The film ends predictably with Howie overlooking the Long Island expressway and, as in the beginning, giving a list of the notorious people who found their demise driving it. “It’s not going to get me.”

A close partner to Todd Solondz’s similarly themed Happiness, L.I.E. was part of American independent film’s development into what it has mostly become today, often referred to as indiewood. By 2001 indie film had turned into a multi-billion dollar enterprise in which major studios were investing loads of cash to successfully navigate a liminal territory between the mainstream and the art-house. There are still uncompromising filmmakers like Jim Jarmusch making conceptual thrillers devoid of easy thrills such as The Limits of Control or unrepentant provocateurs like Larry Clark getting under the surface of the social order. L.I.E., despite its risqué subject matter, barely scratches the surface: the pedophile may be humanized but, in the end, the threat he poses is ultimately nullified. We are living in the age of Juno, Garden State and Little Miss Sunshine. Although L.I.E. may initially seem more “distasteful” and edgy, its faux-tragic conclusion leaves the spectator with a coming-of-age story that ultimately eases rather than exploits tensions.

L.I.E. is restrained by Cuesta’s attempt to appeal to a wide spectrum of audiences, and is therefore too sensitive and morally conservative to burrow deep into American suburbia and truly face what lies beneath. The seminal opening sequence of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet opened a path for others to explore, but very few filmmakers have taken up the challenge, whether “independent” or “Hollywood.” If Firstborn may be viewed as a cinematic translation of the conservatism of the U.S. middle class in the mid 1980s, L.I.E. welcomes the new century by touching upon a social fabric it never fully rips apart.