Don’t Tread on Me

Travis Mackenzie Hoover on The Puppetmaster

Our culture tends towards heroics, and it makes heroes out of people who seem to be doing good. The problem with this is that it makes morals the province of mythic significance rather than the casual everyday: what should be the cost of doing business for a civilized person is suddenly blown up into extraordinary circumstances worthy of lionization. Given that these ethics are often posited as radical—with many of these alleged moral beacon directors frantically boosted as opposition to a Hollywood totalitarianism that strangely mirrors the rhetoric—it seems time, to me, to take one of these cinematic non-messiahs, Hou Hsiao-hsien, and reduce him to the brilliant but life-sized human being that he is.

Frenzied critics declare their faves the way, the truth, and the light, thus positioning themselves as infallible acolytes through their association with such divine genius. This coercive practice has twisted my appreciation of certain members of the elect. For years I waged war against Bresson and Tarkovsky, whose austere fan club kept shaming me for indifference to their “transcendence” and their moral superiority: Bresson had inadvertently encouraged this by writing the Gospels, I mean Notes on the Cinematograph, and Tarkovsky’s prophet-in-the-wilderness posturing only gave the fanboys what they wanted in spades. Other times, I was simply confused when presented with the object: Ozu’s quiet, gracious modesty simply did not line up with the melodramatic shenanigans of his own followers (particularly when combined with the ethnocentric fantasizing of Paul Schrader). And there were cases when what I passionately loved did not line up with the brochures of the critical death-cults. The central tenets of Abbas Kiarostami seemed to advocate judicious intervention and responsible non-interference: this made it strange to read the arrogant puffery of some of his fan club, who ascribed a Ten Commandments element to the gentle moralism that I loved for exactly the opposite reason.

The Puppetmaster is absolutely not a film I want to reduce. I love this film. It’s the Hou Hsiao-hsien film I would take to my grave, the one many others would too. It’s just that “greatness” is not quite the right word to ascribe to such a self-effacing movie. It’s long but not big, complex but not epic, morally committed but not given to proselytizing, and offers no grand spittle in the face of the cruelty of colonization. Instead, it gives us the story of a man who had to organize his life around circumstances he did not want and, through the juxtaposition with the source of those trials (some of which had nothing to do with politics or other alterable conditions), talks of what one has to do when the gods throw thunderbolts at inconvenient times.

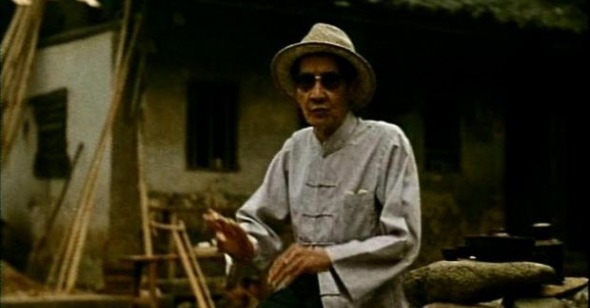

The film tells the life story of one of Hou’s collaborators, puppeteer Li Tien-lu (most famous to Westerners at this point for his appearance in Hou’s Dust in the Wind). He’s on the wrong side of the law from the very beginning, with covert actions required to give him a family name (his parents’ choice of naming him matrilineally contravenes Japanese custom), and the circuitous route to existence pretty much defines the rest of the movie. Li spends his life dodging the unpleasant rules of the game: a switch of parentage with a cousin leads him to be abused, but winds up giving him an in to puppetry; the Japanese occupation makes it necessary to work around the system instead of with it; standard medicine is constantly being rejected for folk remedies that work better and avoid inhuman institutions; and he’s driven underground and into whorehouses when outdoor performances (including all puppet shows) are forbidden.

Li is no stoic defender, no hero of the revolution, no Triumph of the Human Spirit (™). We don’t really hear him espouse a program (unless you count his incessant return to folk medicine, which repeatedly proves useful), we just see him living around the Japanese and dealing with the deaths of various family members. Like most people, he does what he has to do to survive, and in this case he’s suffering under a colonial power. But if he derives moral satisfaction from opposing that power, we don’t hear boo about it. There’s no resentment expressed towards the ideology in specific—and while Hou is careful never to let us forget that oppressive ideology, through the humiliations of official reprimands and ceremonies and the final insult of using his puppetry for propaganda, there’s also no countermovement in the form of angry rhetoric or even elaboration on a theme. Instead, Li carries on regardless. The important point is not the clash of civilizations but the measures to which one victimized civilization must go to accommodate another when it expands its borders and invades.

In The Puppetmaster, nobody throws down or has a big emotional confrontation. Hou’s handling of various characters’ deaths is usually circumspect—the moment gets a build-up, only to be described by Li’s sudden appearance as an on-camera documentary subject. To me, this is a bigger emotion: we are made aware of an involuntary passing through its inevitability, via Li’s years-after-the-fact recollections. But it would be a mistake to see this as a stoic shouldering of heroic burden: in Hou, these are the rules of the game. You do have to accept them, but you don’t have to like them- and he manages to suggest both by taking away power over the event while nailing you with the melancholy of the implication. Nobody gets any points for suffering: it’s just that certain practical considerations make it necessary.

This point drove certain lefty elements out of its mind—to condemnation at home, and mindless praise abroad. Seizing on the passivity of much of the New Wave, Taiwanese detractors insisted that nobody actually resists in these movies—they sort of take what they’re handed and go about their miserable business. Meanwhile, in the West of the poststructural era, we were stoked on a simplistic postcolonialism that assumed that all such enterprises were exactly the same, and that all their expressions were Che Guevara in spirit. (This mentality is epitomized by Frederic Jameson’s famous essay on Edward Yang’s The Terrorizers, now forever being debunked by Chinese-language film scholars who object to his deeply reductive approach: Western po-co in its Eighties-Nineties heyday rarely amounted to much more than “Postcolonialism is awesome! Every home should have some!”)

Neither of these broadly defined political approaches deals properly with Hou or The Puppetmaster. While the Taiwanese argument seems more reasonable (perhaps for being culturally specific), it omits the ground-level needs that motivate politics: comfort, security, safety, well-being. Hou’s masterpiece is an essay in going about the business of acquiring the basic human needs in the face of colonialism. The struggle does not begin and end with polemics and agitation; it demands day-to-day negotiation with and avoidance of the enemy. These are things that traditionally pedagogical political filmmaking has lived to deny. If there is a valid point in stating that Hou has erased activism and resistance (and it’s a hard charge to dismiss completely), there is also the sense that the converse is true, that reducing everything to The Struggle tends to obliterate the very mundane existence that politics are supposed to secure. As for the opposite Western misunderstanding, the awareness of politics and oppression does not automatically equal activism: the distortion of any vaguely ideological gesture as a violent blow for freedom does nothing but pay compliments to critics and turn every political impulse into one barely differentiated mush useless to student and guerilla alike.

Hou is neither throwing in the towel nor raising his voice: he is simply stating the colonial victim’s eternal wish of “don’t tread on me.” Life and art are for the living as opposed to the keepers of meaning and purpose, keepers who are forever muddying the relationship between theory and practice when the mood strikes them. I am reminded of a Canadian filmmaker named Terrance Odette who once used Hou and Kiarostami to bolster his program—which he interpreted as "repressing" what American films gave, as opposed to redefining what to give and what to omit. I think this was supposed to show how he himself had "repressed" that Yankee influence, but his agonized, guilt-ridden Sleeping Dogs bore no resemblance to Hou in any sense. To sell Hou on such stoic moral grounds is to miss the point. One should think of him not as a savior-artist with orders from the top, but as representing a return to art as an extension of our unimpressive but vital earthly considerations. Hou may not save you, but he sure wishes you well. In strident times in which we live (in which we always live), that’s one hell of a relief.