Light in the Dark

Ohad Landesman on Night and Fog

“If I had found an actual film,” Claude Lanzmann is famously quoted saying, “a secret film, since that was strictly forbidden—made by an SS man and showing how 3,000 Jews, men, women, and children, died together, asphyxiated in a gas chamber of the crematorium 2 in Auschwitz—if I found that, not only would I not have shown it, but I would have destroyed it.” Only eight years after Lanzmann erected a circle of flames around what he considered to be the intransmissable horror of the Holocaust, shooting his Shoah (1985) entirely in the present, an infamous scene from another film had established itself as one of the most controversial Holocaust recreations in cinema. Schindler’s List’s quasi-pornographic shower scene in which both audience and the terrified naked women in Auschwitz are relieved to find out that clean water is coming out of the pipes of the gas chambers, exploits collective memory to provoke suspense, and invades an imaginary space of catastrophe, giving almost no respect to the magnitude of horror and sheer human misery of the place.

The appropriateness of using Hitchcockian voyeurism and suspense to manipulate audience’s responses in a scene of this nature might remain debatable. Steven Spielberg, however, chock-full of good intentions to recreate the events of the Holocaust for generations to come, but indifferent to the moral consequences of what might simply be artistic chutzpah, failed somehow to distinguish form from content, or to remember Jean-Luc Godard’s provocative dictum from years earlier, according to which “tracking shots are a question of morality.” Because by moving his camera into this ‘forbidden’ space, Spielberg’s aspirations become morally problematic; he not only attempts to reenact the past by bringing it into the present, but also to depict historical moments of intolerably cruel deaths, a somewhat obscene desire which stems its legitimacy from the fact that Spielberg would not show actual gassing, but only a staged representation. In other words, since the gas chamber turns out to be not a gas chamber at all but a real shower room, the scene regains moral legitimacy only at the last moment, when the forbidden enactment of genocide becomes permitted only because it is artifice.

Alain Resnais’s Night and Fog (1955), considered by many the most aesthetically sophisticated and ethically flawless film about the Holocaust (François Truffaut once hailed it as the greatest film ever made), succeeds, in my view, at least where Schindler’s List fails 38 years later. Resnais’s smooth, mobile camera, gliding across the grass, moving inside the abandoned structures of the concentration camps, and penetrating the gas chambers for the first time in cinema history, functions as a post-factum investigator, and acknowledges its own limitations. Departing from the premise that to represent the Holocaust on film is an act which denies the enormity of horror and the singularity of the tragedy, Night and Fog excavates the dreadful past lying beneath the deceptively banal landscapes of the present day, landscapes which, like those in Lanzmann’s Shoah, are at times startlingly beautiful with blue skies and orange trees. Being somehow an anti-documentary which reflects, questions, and interrogates our own responses to it, Night and Fog is an essay-film which consistently negates the representational, indexical power of film images, and never stops meditating on the problematics of its very existence, a work of high modernism.

My denunciation of the ‘realist’ tradition in Holocaust films to which Spielberg belongs, along with my warm appraisal of Night and Fog for its refusal to represent the unrepresentable involves, as I must admit, some sort of an unconscious theological premise, a leap of faith on my part. As has been noted many times before in this everlasting discussion of the film, condemning Schindler’s List on the grounds that the horrors of the Holocaust render any attempt at direct representation obscene is a quasi-religious invocation of the Second Commandment, a moral stance which points to the singularity of the Shoah and claims its status as an event which is ultimately outside history. I also understand that to repudiate Holocaust realist cinema as a worthy object of analysis and align with political modernist agendas is also to hold Hollywood cinema, for its deceptiveness and illusionism, against an avant-garde cinema whose task is to promote a critical awareness of the materiality of the medium. I am, it has become apparent to me, a spiritual purist in this matter.

Cinema, some argue, is an ethically and metaphysically problematic medium when it comes to represent death. For many classical theorists of cinema, such as the Catholic André Bazin, any attempt to render death visible onscreen is doomed to become obscene. Unlike any of the moments cinema can represent over and over again, death is perhaps the unique moment par excellence; it is the last. Resnais, highly aware of the medium’s potential to relive past instants in an eternal present, embraces this spiritual thinking and brings to the front the necessity of remembering history without using any moving images of death and catastrophe. Sacha Vierny’s camera, gliding past the now-empty barracks and crematoria until it can go no further, momentarily pauses before it enters The space in order to acknowledge its own limits, giving turn to the narrator who warns us of what the camera is about to reveal: “The only sign—but you have to know—is this ceiling, dug into by fingernails. Even the concrete was torn.” The fingernail marks on the gas chamber ceiling, made by the death struggles of its victims, not only require pre-existing knowledge of history, but are also evidence to what we can no longer escape knowing; all we can do is imagine, not see.

Resnais, determined to shock audience out of their ignorance and indifference, alternates between present images and atrocious archival footage, inquiring about the status and the truth value both have. As the camera travels around the concentration camps, the narrator throws out skepticism: “we go slowly along them, looking for what?” Unable to find the right words, he intones: “these images are taken a few minutes before an extermination… but we can no longer say anything.” Resnais, as William Rothman once suggested, uses cinema to explore the danger of art becoming complicit with death, horrific by its own means. When Night and Fog takes us to the SS hospital, the camera pans across black-and-white stills of patients, until in one of them, an eye blinks. Looking at what first seems like a photograph, we feel protected for a short while; history had already happened, and we do not have to participate in its forward motion. But then, as the reanimated motion of the man’s eye creeps on us, we cannot help but await with him his death, which we know is about to come.

Night and Fog dialectically counterpoints image with sound, past with present, and stasis with movement to set up a thematic tension between our responsibility to remember and the impossibility of doing so, between memory and oblivion or denial. Hans Eisler’s ironic score contrasts beautiful lyrical flute passages with disturbing images of deportation, typhus, and corpses buried by bulldozers. The narration, read as a third-person unemotional commentary by a professional actor, prevents sentimentalism and forms an incongruity between what we see and the way we are led to react to it; “The camps come in many styles,” the narrator enlightens us as the camera glides across different designs of watchtowers: “Swiss, Garage, Japanese, No style … a concentration camp is built like a grand hotel.”

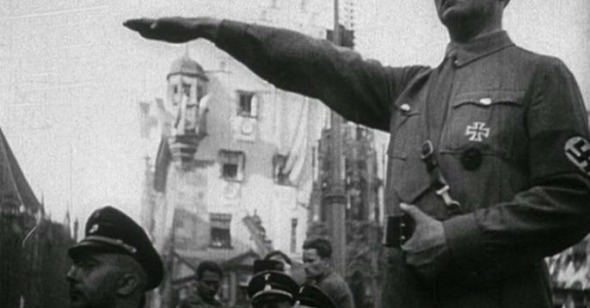

Eric Rohmer once said that Resnais is a cubist because he reconstitutes reality after fragmenting it. Night and Fog is formally constructed as a visual synecdoche, evoking a major chapter of history from a few traces remaining. Moving from concrete evidence to general scenery, from fragmentation to universality and abstraction, the film never allows us to forget that the Holocaust concerned the extermination of millions of individuals; for a film with no characters or heroes, Night and Fog keeps the execution process basically dehumanized, turning its victims to collective signs for the Genocide. Resnais was blamed over and over again for not calling sufficient attention to the Jewishness of the atrocities; apart from several images of Stars of David, and a very well-known photograph of a frightened Jewish child raising his hands before a German trooper during the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, the film fails to mention not only Jews, but also Germans or even Germany itself. The last sequence, a visualization of the argument concerning the banality of evil, abandons the detached modernist tone and ends up with a didactic cry: “Who is then responsible?” When there is nothing left but ruins and desolation, a tragic vision of a world destructed by an undetermined abstract force defines what would eventually become a recurring theme in Resnais’s work: the wrath of God.