Home Alone

Max Nelson on Shireen Seno (Nervous Translation)

Shireen Seno, one of the central figures in the newest generation of the New Philippine Cinema, has described herself in interviews and festival notes not as a filmmaker but as a “lens-based artist,” a distinction that captures the range and breadth of how she argues images can be made. In the past six years she has accumulated a body of ingenious, densely textured films—several shorts and two features, of which the more recent, Nervous Translation, premiered at the Rotterdam Film Festival this January. She has published artists’ books of her photographs, worked for years with the arts collective Tito & Tita, and curated an “experimental film exchange” with filmmakers from Tokyo and Manila. What might for another filmmaker have been separate pursuits have come to seem, in Seno’s case, like branches of a single project. She approaches filmmaking and curatorial work as two related forms of preserving memories at risk of erosion or neglect.

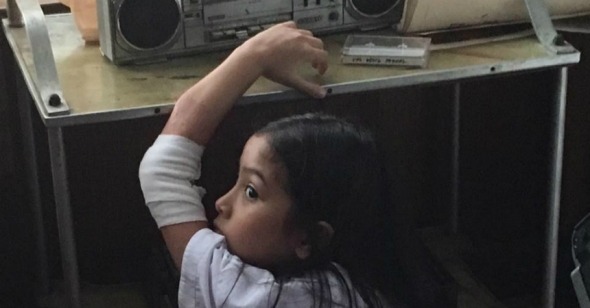

Nervous Translation is Seno’s first digital film and the first for which she’s immersed us in a time and place directly rather than through the filter of an anachronistic style. We spend the film tracking the subtle shifts in tone and power between Yael (Jana Agoncillo), an eight-year-old girl, and her mother Valentina (Angge Santos), a factory worker, in their large Manila house. It is 1987, a year after the People Power Revolution put an end to the Marcos dictatorship. Yael’s father, we learn in brief asides, is one of the Filipino workers who in these years found jobs in Saudi Arabia and had to leave their families at home; she spends her time making herself tiny meals and listening covertly to the tender cassette tapes her father made her mother as mementos of their love.

Visitors and outsiders—family friends from Japan; Yael’s garrulous rock star uncle—keep adjusting the rhythm of their otherwise solitary life. The movie’s connective tissue thins and stretches but hardly ever breaks. It stays together due in large part to the careful, patient way Seno delineates the space of this house, lays out the daily movements of the pair who make their life in it, and sustains the soft but well-defined textures of the images that bring it across.

Embedded in this delicate pattern are clips of the videos and TV shows that give Yael some of her few links to the world: a gory zombie movie; an episode of a Japanese superhero series; a news broadcast about the aftermath of the revolution; and an advertisement—also Japanese—for a fountain pen that catches Yael’s interest and pushes the movie into more surreal, dreamlike territory. That last delirious commercial was staged, but the rest are real films—just not always the ones they claim to be. The zombie movie is a Cebuano horror film from 2011; the superhero footage comes from a 2013 drama about a Filipino father who moves to Japan and gets a job on a fictional TV show that resembles, in turn, the hit 1970s franchise Super Sentai.

Seno has said that Nervous Translation emerged from her memories of “growing up a reluctant child of the Philippine diaspora.” She too was very young in the late 1980s—she was born in 1983—but she was raised in Japan, where her parents had emigrated during some of the grimmest of the Marcos years. Her breakout film, Big Boy (2012), centered on a family in rural Mindoro who, during the Philippines’ first years as an independent republic, stretch their son out on a rack every morning and feed him elixirs to stimulate his growth. It was a shrewd fable about the poisonous lessons of economic competition that the U.S. empire had left behind. But what set it apart were its format and style. Seno shot the film on gauzy, incandescent Super-8, cut each scene down to a set of arresting, almost free-floating images, and spliced them together as if they’d come from a stock of home movies. A torch-lit procession, a nightmarish doctor’s visit, and visions of a gathering storm emerge from between relaxed scenes of children playing and families sitting down to meals.

Big Boy was been “loosely based,” Seno told an interviewer in 2011, “on stories from my father about growing up in Mindoro in the 1950s,” and Nervous Translation evokes the childhood she might have had if she had grown up in her parents’ home country rather than abroad. In both cases it is as if Seno had found that introducing archaic visual documents into a film—home movies, horror movies, commercials, news broadcasts—could be a way of recording something that would otherwise have been forgotten or unimagined.

In 2014, she and the artist Merv Espina began a more literal effort to recover the country’s forgotten images. They assembled a pair of programs of short films from the Philippines and toured the movies, with some variations, around the world—Toronto, Tromsø, Jakarta, Tokyo, Auckland, Brooklyn—under the name “The Kalampag Tracking Agency,” after a Tagalog word that for them suggested “a rattling sound or a bang, usually used in reference to machines.” They chose that name, they wrote, because it “implies that the machinery is somehow damaged. Or perhaps it never really ran smoothly.”

One of the machines they had in mind was their home country’s apparatus for preserving its short, nonnarrative, and experimental films. During and after the period of Ferdinand Marcos’s repressive right-wing regime, they remind us, decades’ worth of such movies had been left to turn to “vinegar and dust.” A National Film Archive never emerged under Marcos and after his rule took decades to arrive. The Kalampag Tracking Agency became a way of redressing that lack. Films from the 1980s and early 1990s that had been luckily preserved—in optical printing workshops hosted by a German director in Manila, for instance—could be both brought to new viewers and restored using the facilities of the institutions through which the program moves. Film exhibition, Seno and Espina realized, could be a method of film preservation by other means.

So could filmmaking. Alongside earlier filmmakers like the animator Roxlee and the new media pioneer Tad Ermitaño, the Tracking Agency programs include shorts by Seno’s contemporaries and collaborators, including Tito & Tita, Raya Martin, and John Torres. These are filmmakers for whom the collection and preservation of imperiled movies is both a dramatic subject and a job to which films themselves can contribute. Martin’s feature The Great Cinema Party (2012) centered on a group of cinephiles who commune with silent-era Philippine movies on an island that had a part in the Pacific War. Torres’s beguiling Lucas the Strange (2013) included footage from a 1974 romance by Ishmael Bernal, one of the major Philippine filmmakers of the 1970s and 1980s; his most recent feature, People Power Bombshell: The Diary of Vietnam Rose (2016), turns on clips from an unfinished movie by another such director, Celso Advento Castillo. Those films still need rescuing in archives and labs; but it was a powerful idea that, when the standard channels failed, filmmakers could turn their movies into backup archives. Moreover, because they were making fiction films, they needn’t limit themselves to movies that had survived. One found film could “play” another, like the movies on Yael’s TV in Nervous Translation. Films that had never existed, or had long ago turned to dust, could be invented or reimagined from scratch.

Those ideas have done much to animate Seno’s own work. Big Boy was followed by a pair of brief Super-8 reveries called Lovebird-watching and Trunks, then by a lush, playful short called Shotgun Tuding (2014). This poked affectionate fun at another legacy of American colonial rule: the kitschy “pancit westerns” the Philippine film industry produced in the late 1940s, in which Filipino actors, the scholar Nick Deocampo has noted, “became Mexicans, Indians, and even American cowboys.” In Seno’s belated entry in the genre a gun-slinging woman, played by Chantel Garcia, hunts down the beekeeper who seduced and abandoned her sister and leads him through a set of desolate landscapes.

That it was shot on washed-out 16mm made Shotgun Tuding, like Big Boy, seem like an object salvaged from the precarious period in which it was set. Together, these movies became a kind of imagined archive. They gesture toward the wealth of strange, beguiling images we might still have if the country’s early cinematic output had been better preserved. They impose a kind of distance between themselves and the viewer; it’s as if they were found objects Seno had stumbled upon and screened.

Nervous Translation is filled with quiet images of Yael’s home that glow with intensity and precision: curtains rustling against glass; wrought-iron chairs emerging from the backyard; wood chairs with floral patterned cushions; a bronze relief sculpture; a leather suitcase tucked under a couch. Early in the film, we’re given an inventory of these neatly arranged fixtures as the house brightens and dims on a cloudy afternoon. The scene has the lucid, exact quality of a recollection surging into clarity. It suggests, more subtly but no less acutely than Seno’s earlier films, her preoccupation with filling the gaps the Marcos years left: the lost films and videos as well as the memories of the Philippines that she and other reluctant children of the diaspora never formed. The memories might never have existed, just as the movies might have vanished or decayed. But they can be remade.