A House of Games

Damon Smith on The Face You Deserve

“Reality’s a dream / a game in which I seem

To never find out just what I am

I don’t know if I’m an actor or ham / A shaman or sham

But if you don’t mind ... I don’t mind.”—Buzzcocks

Last October, as Hurricane Sandy churned the Atlantic coastline, I found myself marooned at a film festival in Sâo Paulo. Though it was run by some genuinely hospitable, fun-loving people, after months of travel I couldn’t get into the celebratory spirit. Fatigued by an endless intake of new cinema from every corner of the earth—China, India, Argentina, France, the Philippines—I was frankly sick of films and cine-chatter. After attending to the business that had brought me there, I set out to explore Brazil’s pulsating metropolis on foot and by subway, studiously avoiding the screenings that should have held me captive at least part of the day. The universe of movies seemed blissfully distant; it was easy to forget (and hard to care) there was a festival happening at all.

Guilt finally caught up with me. Fighting movie ennui one afternoon, I resolved to spend some time in a darkened theater, hoping to take away a fact, an image, a glimmer of pleasure. The film I went to see that day was Miguel Gomes’s little-seen 2004 debut The Face You Deserve (A Cara que mereces). And for the next 108 minutes—after a long season of discontent—my infatuation with cinema was restored, unequivocally and profoundly so. I rediscovered again how it feels to be in love with a film, to fall into the “magic window” of the screen, as Walter Murch once described it, and succumb to the spell of moving images.

One of Portuguese cinema’s latter-day trickster figures, Gomes tosses convention aside with each of his remarkable films, whether it’s the bird-squawk Dada dialogue of his early short Kalkitos or the deliriously nimble format of his colonial fantasy-cum-silent film Tabu. You feel Gomes trying to redefine the very rules by which stories can be formulated and rendered in cinema, and his playfulness is infectious. Even so, I was hardly prepared for the many obscure pleasures (fey musical numbers, wild tonal shifts, schizoid editing) of his shape-shifting maiden feature, about which I knew nothing. The Face You Deserve, a film about the psychic hangover of childhood and the transformative nature of cinema itself, is far stranger (“uncategorizable” is the word sympathetic reviewers seem to favor) and certainly funnier than his acclaimed, subsequent features Our Beloved Month of August and Tabu, though it shares with both an unusual degree of tenderness toward its characters.

Cross-pollinating Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs with classic Hollywood musicals and the arch meta-games of Jacques Rivette, the film unravels as a comic portrait of Francisco, a sulky grade-school teacher who, experiencing an early mid-life crisis, falls under the spell of an enchanted house. Scenes route suddenly from deadpan comedy and arch satire to musical romance and back again, all bathed in a light wash of Portuguese saudade (the famously indescribable melancholic state linked to nostalgia, homesickness, and disappointment), before the film quietly morphs into a slightly bonkers woodland fantasy not far removed from Céline and Julie Go Boating. Games are afoot, things go bump in the night, and mysteries abound as dreams and reality merge during the hero’s convalescence in a creaky country manor. Somehow, Gomes manages to weave in a thread about The Ugly Duckling, a plague of centipedes, and a monster that lives behind the darkened door beside Francisco’s scarlet-hued sick room, sourcing these childhood fears—social rejection, creepy-crawlies, the unknown—in the subconscious of the recuperating Francisco. Paying tribute to the Euro modernism of the past century while forging new modes of storytelling in this one, Gomes (who still shoots on 16mm film) is a maverick, and his anything-goes approach is a pure pleasure to experience.

Face opens with a visual right out of the Snow White story: a gold-crested ornamental looking glass, magically hovering on a solid black background between parted red stage curtains, reflects curling wisps of bluish smoke. “At 30 years of age, you get the face God has given you,” reads the on-screen inscription. “After that, you get the face you deserve.” Light applause erupts over a harmonium doodle on the soundtrack, and Gomes cuts to a bus stop where a sailor, quaffing a beer, is waiting for an approaching coach. As the bus motors away, the camera zooms in to reveal a thin, dark-haired man clownishly attired in cowskin chaps, neckerchief, Stetson, and an ill-fitting vest pinned with a sheriff’s badge, suggesting a real-life incarnation of Toy Story’s Woody. He’s holding a ukulele case. Thunder sounds, the cowboy squints up at the sky and sneezes, his hat popping into his open hand with vaudevillian precision, Chaplin-style.

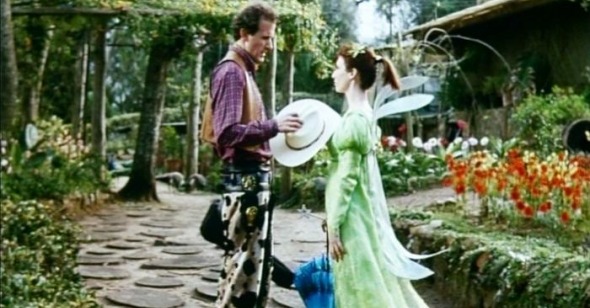

Thus we are introduced to Francisco (José Airosa), on his way to a party—and a student production of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs—he’s in no mood to attend. Walking in the rain with his sweetheart Marta (Gracinda Nave), a schoolteacher done up as a fairy godmother, he grumbles about life in Lisbon while she dreamily warbles a fado-like number, accompanied by plaintive soundtrack music, about the disappointments of growing up, her sweet-sad lyrics referencing starfish, the Sex Pistols, and the NASDAQ as emblems of Francisco’s fleeting pleasures and unfulfilled hopes. On top of everything else, his grumbling asides reveal, it’s the eve of his 30th birthday and the couple has made plans, now delayed, for a country outing.

The next few scenes of Face’s extended prologue (“First Part: Theatre” reads an intertitle) further establish Francisco’s general state of unhappiness and essential childishness. His mock contempt for actual children and juvenile interactions with nearly everyone in his orbit are all played for laughs: he steals the kids’ Snow White stage apple and lies about it, munching the pilfered fruit conspicuously a moment later; makes out with Vera (Sara Graça), a female colleague he’s been flirting with blithely; ridicules a boy who’s just gotten stitches in his chin; and bullies another youth harmlessly crushed out on Marta, causing her to stalk off into the night. Meanwhile, he hasn’t been feeling well. (“Don’t be a sissy,” says his doctor, examining Francisco after a minor car accident.)

If there’s a jocular and almost carnivalesque atmosphere in Face’s first part—scenes are punctuated with visual gags (a child’s robot costume; a street mime’s kissy-face routine), sound effects (Gomes outfits Marta’s wand and Francisco’s toy gun with B-movie sonics), and endless sophomoric zingers (“Is it a poo or a pee?” he teases Vera, on her way to the ladies’ room)—the farce yields gradually to considerations of mortality. At the end of the evening, Francisco’s alone at a bingo bar listening to a Cuban band’s rendition of Álvaro Carillo’s bolero hit “Sabor a mí.” Someone has scrawled the word FAGGOT on his back. Gomes holds on a long close-up of Francisco, staring wanly at the bartender offscreen who has just refused to serve him a beer at closing time. His face is an arrangement of defeat and self-pity—a child refused his favorite toy, a grown man frustrated with aging and a bummer birthday, a lonely soul feeling twinges of existential sorrow. There is something moving about this shot, one of the few moments Francisco ceases to be an instrument of irony. A few beats later, Gomes flips the humor switch again, and a trickle of blood suddenly erupts from his nostril.

Thirty minutes in, The Face You Deserve begins its transition into an entirely different tonal register, initiating the hero’s complete vanishing as a physical presence in the film. Traveling to the countryside without Marta, Francisco wakes from a nap on the bus disturbed by giggling phantoms (two smiling men’s faces can be seen reflected in the coach window) and absent-mindedly fiddles with his uke. Gomes cuts to a POV shot of a winding dirt road, and Marta’s sing-songy, nursery-rhyme voice reprises her earlier fado, the lyrics alluding to Francisco’s worsening cold: “You are sick.” Owl hoots and other nocturnal birdcalls—sounds that will become important elements of the film’s overall sound design—are heard for the first time. Arriving at the old house, he wearily climbs stairs to a garret-like room and pokes around in a chest full of classic children’s toys. The next morning, his face is covered with an ugly rash. Gomes recycles the image of the smoke-reflecting looking glass while we hear Francisco utter the famous “mirror, mirror on the wall” incantation. “Second Part: Measles,” reads an intertitle.

*****

Over three creatively freewheeling features, Gomes has shown a predilection for sudden narrative leaps and a fondness for creating discrete sectors within the space of each film, introducing storylines that connect obliquely, like stanzas of a lengthy poem written in radically different meters, some in sonnet form and others in free verse. Our Beloved Month of August entwined independent strands of music documentary and melodramatic realism to create a unique, moving vision of everyday life and romance. Tabu’s disparate three-part tale of erotic fate in the African tropics yoked colonial nostalgia to cinematic legacy to bewitching effect. In The Face You Deserve, there is a more personal accent to the ruptured narrative structure and the theme of childhood versus maturity that ribbons the reluctantly aging Francisco, who eventually diffuses into seven distinct male personalities (Copí, Gross, Talvassos, Harry, Texas, Simões, and Nicolau) played by different actors, each introduced with Little Nemo–like storybook illustrations. To wit: Face was conceived on the heels of Gomes’s thirtieth birthday, and co-written with Portuguese filmmaker Manuel Mozos (Xavier), whose own anatomy of a life crisis, When It Thunders (1999), inspired Gomes to echo certain elements of that film’s wood-fairy conceit. He also cast Mozos to play dapper Harry.

The ailing Francisco’s self-quarantine also begets the film’s most important phase change, as the seven frolicsome caregivers who appear in the house—dreamlike projections of the unconscious, as it were, analogous to the watchful, merrymaking dwarves in Snow White—inhabit a make-believe world of which they are the sole inhabitants. The bucolic locale becomes a playground of sorts where an obscure game is underway, complete with a list of forbidden words (“otolaryngologist”) and a long list of bizarre rules (“It is forbidden to count footsteps”) enumerated in Francisco’s mantra-like, tongue-in-cheek voiceover. The men play hide and seek and musical chairs, but their real task (“Seven to take care of me”) is to minister to the invisible “patient,” who must heretofore, according to his absurd commandments, remain unnamed. Gross (Ricardo Gross) is obsessed with food, Copí (António Figueiredo) with sex (he has a litter of smut mags hidden in the bathroom), while the others engage in horseplay and bicker over petty grievances, leaving the youngest and most gallant, Texas (Tabu’s Carloto Cotta), to shoulder the blame for their transgressions; in this sense, each embodies aspects of Francisco’s psyche, the conflicting drives and desires that his waking consciousness unifies into a coherent “I.”

The instability of the self is a current in modern world literature from Pirandello and Poe to Woolf, Joyce, and Pynchon, but was given a uniquely concrete form by Fernando Pessoa, the great 20th-century modernist whose literary temperament and intensely interior works continue to cast a long shadow over Portuguese artists as disparate as Manoel de Oliveira and José Saramago. Writing under a variety of aliases, or “heteronyms,” each with a distinct voice, personal history, and point of view, Pessoa constructed a technique, still unrivaled in its many aesthetic permutations, for giving expression to the idea of the self as a centerless center. There’s a reverberation of this motif in Gomes’s use of polyvocal layering and fantasy characters who, at different moments, seem to be channeling Francisco, an absent presence whose whispered thoughts they hear, sense, and respond to. Sometimes he addresses the seven men collectively (“Well done, lads”) or influences them subtly, by means of schizoid interference (“Be brave, Harry”). At other times, Francisco’s self-referential voiceover melds all into one (“He is himself. We are ourselves”), suggesting the complete commingling of their beings.

Identity-as-otherness obsessed Pessoa, who developed a lifelong interest in spiritualism and the occult, evident in his vigorous correspondence with Magick charlatan Aleister Crowley. His literary style, through which “Pessoa” is overtaken by others (Bernando Soares, Álvaro de Campos, Alberto Caeiro, and Ricardo Reis being the most famous), is actually a form of mediumship. Writing becomes a kind of séance, a trance state, and the writer himself a vehicle for “the expression of moods that became so intense that they grew into personalities and made my very soul the mere shell of their casual appearance.” This idea resonates in the mysterious incarnation of the seven dwarves, flesh and blood characters onscreen no matter how imaginary they might be in the loopy logic of the film, and the physical vanishing of Francisco, in whose mind-world they seem to dwell. (Other spirits flit about, too, as is clear in Texas’s conversation with a flea.) Sleepwalking, catatonia, and isolative or undecidable states of being (Nicolau’s pill-induced trances; Francisco’s off-screen convalescence), are further emphasized within The Face You Deserve, part of the fabric of everyday life in the mythical world of the country house. In this and other respects, Gomes’s playfully nonlinear narrative also evokes the hermetic rituals and role-playing adventures of Rivette’s titular heroines in Céline and Julie Go Boating. (Céline and Julie’s fiction-enhancing, memory-wiping candies have an analogue in the dwarves’ array of somnambulatory pills, and the protagonist “mediums” in both films are under the spell of an old house.)

So where is the story going? It’s a legitimate question to ask of The Face You Deserve. Even the characters themselves appear to be wrestling with it. In one of the film’s most brilliant sequences, Harry tells Copí a story that splinters into several others involving Simões, Gross, and Nicolau (João Nicolau), a fish pond, and a cave filled with pirate treasure. When he introduces a third strand involving the retelling of an unrelated incident, Copí complains that he can’t start another tale until he’s finished the first. “It takes some patience to listen to stories,” says Harry. “Otherwise we’d just tell the beginning and the end.” True to the middle, Gomes proliferates the fictional game (when Harry sneezes in the “real” world, so does Gross the pirate in his treasure cave) before arriving at Nicolau’s recounting of a premonitory dream in which he solemnly buries a grasshopper. Like Copí, or the auditors of The Thousand and One Nights, we might be confused as to just how many narratives we are embedded within, yet the vortex is mesmerizing. Near the tail of this multi-cocooned sequence, rendered in Rui Poças’s low-light detailing and elegantly serpentine camerawork, Nicolau, Travassos, and Texas bear witness to each other’s magical transformation into animals. It is nighttime in the woods. When they whisper each other’s names, Gomes cuts to images of a pig, mule, owl, and heifer, while a man’s moan of agony is heard offscreen, a clever construction that calls to mind The Metamorphoses of Apuleius as well as one of Robert Bresson’s famously inscrutable animal sequences in Au hasard Balthazar. The game we are playing is called cinema.

Obscure and open-ended, yet benevolent in its aim to recuperate a vanished sensibility with whimsy and humor, The Face You Deserve is forever elusive. It is as much about filmmaking itself—the rules that constrain expression and life, the youthful push against convention and what’s expected of “mature” filmmakers—as it is the chronicle of a life crisis that acquires an interior and imaginary dimension. Filmmaking itself exists in such an imaginary dimension, and for artists like Miguel Gomes or the late Chilean master Raúl Ruiz, who once envisioned a film composed of mythic images occupying multiple dimensions, the phantasmagoria of imagination reigns supreme. At its best, animated with a spirit of childish wonder and yes, even silly behavior and outlandish ruses, cinema can flourish. What’s truly inspiring today are works like The Face You Deserve that, in the process of renewing the language and conventions of narrative cinema, embody freedom, joy, a sense of play, and limitless possibility. Presuming we receive such eccentrically designed invitations with an attitude of acceptance, we may hope to share in that elation. Perhaps then, too, we will get the cinema we deserve.