A Time to Kill

Chris Wisniewski on Killer of Sheep and Bubble

Intention aside, even the most talented filmmaker’s commitment to a certain kind of realism can leave him precariously perched between sympathy and pity, social engagement and smug condescension. It’s easy to avoid self-reflection by way of vaulting each new entry by the likes of Abbas Kiarostami or the brothers Dardenne into a canon that already includes the great works of the Italian neorealists. The accomplishments of these films can be enumerated easily and unselfconsciously, though realism itself, as a cinematic ideal and practice, remains the purview of a social and intellectual elite: People like us use their position of privilege to make movies about them, the underprivileged many, all for the enlightenment, edification, and, yes, entertainment, of people like us. The realist filmmaker crafts art for our consumption using the lives, and often the suffering, of the Other as his raw material, and while there’s something praiseworthy in giving a voice to those often denied the opportunity to speak for themselves, this sort of filmmaking can’t be evaluated with a simple rubric (e.g., amateur actors who are non-white=socially engaged; amateur actors who are disabled=condescending).

When a filmmaker, in the service of a rigidly delineated aesthetic code, turns his camera at the so-called real world, we rarely pause to ask the most nagging of questions, “Who is this film being made for?” The answer separates blind adherence to an arbitrary set of rules from the possibility of a real alternative cinema. Realism, as an artistic aspiration, isn’t about rules, codes, or standard practices; rather, its value lies in the way it can challenge convention and shock us into new ways of seeing.

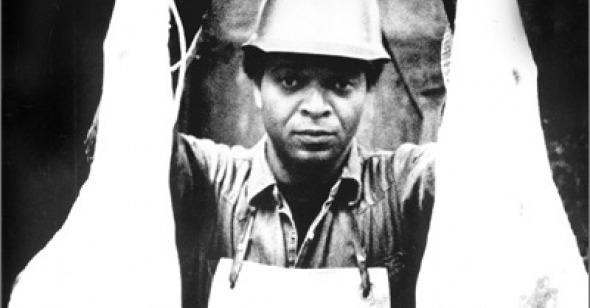

The greatest and most heartfelt of all realist American films—Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep—succeeds not through formal rigor but through generosity of spirit. Burnett’s episodic 1977 film, which traces the day-to-day experience of a struggling slaughterhouse worker and his family in Watts, Los Angeles, dispenses with every rule of conventional narrative filmmaking, refusing to bring any preconceived judgment to the lives of his characters. It’s as though the fiction he presents, crafted of the pain, joy, and poetry of the everyday, manifests itself to us on its own terms, with Burnett serving more as its mediator than its author.

Conversely, when a filmmaker like Steven Soderbergh sets off to challenge convention conventionally, as he does in his latest film Bubble, he damns himself to a willful disregard for decency and good taste. Bubble begins as a sort of anthropological look at the lives of a handful of working-class Midwesterners and evolves (or rather, devolves) into first a love-triangle and, later, a murder mystery. Soderbergh’s film reduces the raw material of real lives into a detached aesthetic enterprise, as his obsession with form smothers the possibility of empathy.

![]() What’s most interesting about Bubble, though, is that, in spite of its perverse condescension, its claims to realism are fairly similar to Killer of Sheep’s. Both Bubble and Killer of Sheep were made outside the Hollywood system—Soderbergh’s hi def “experience” was an independent production released simultaneously on DVD, on television, and in the theaters; Burnett’s 16mm masterpiece was a student project which never received a major commercial release. Bubble was shot where it’s set, on location on the border between Ohio and West Virginia, with an amateur cast all drawn from the local population. Killer of Sheep, too, was shot on location in Watts, again with amateur actors. Bubble obeys many of the codes of aesthetic realism, set down over nearly a century by the likes of Bazin and Kiarostami, and though Burnett first studied the Italian neorealists after he’d conceived Killer of Sheep, his filmmaking often draws comparison to that movement: he’s content to leave his camera fixed on the minutiae of everyday life, be they a woman rubbing lotion on her legs or children playing in an alleyway.

What’s most interesting about Bubble, though, is that, in spite of its perverse condescension, its claims to realism are fairly similar to Killer of Sheep’s. Both Bubble and Killer of Sheep were made outside the Hollywood system—Soderbergh’s hi def “experience” was an independent production released simultaneously on DVD, on television, and in the theaters; Burnett’s 16mm masterpiece was a student project which never received a major commercial release. Bubble was shot where it’s set, on location on the border between Ohio and West Virginia, with an amateur cast all drawn from the local population. Killer of Sheep, too, was shot on location in Watts, again with amateur actors. Bubble obeys many of the codes of aesthetic realism, set down over nearly a century by the likes of Bazin and Kiarostami, and though Burnett first studied the Italian neorealists after he’d conceived Killer of Sheep, his filmmaking often draws comparison to that movement: he’s content to leave his camera fixed on the minutiae of everyday life, be they a woman rubbing lotion on her legs or children playing in an alleyway.

If the question is film form, though, then Bubble—even more so than Killer of Sheep—is an almost unqualified success. The visuals, with their striking depth-of-field, are crisp and vibrant. The long takes, which rarely cut to close shots, complement the rich detail of the hi-def images. Nondiegetic sound only invades in sparse and brisk interludes, which usually trace the routinized workdays of the film’s characters, most of whom work in an Ohio doll factory. Bubble is certainly impressive, but I hasten to mention that the effect of these long, often silent takes is to leave Soderbergh’s very ordinary Midwestern characters, portrayed ineffectually by his amateur stars, awkwardly captured by his pitying camera. These people commiserate only tentatively, stuttering their way through their fast food lunches. Martha (Debbie Doebereiner) and Kyle (Dustin James Ashley), two thirds of Bubble’s central love triangle, seem to have nothing to say to each other: Martha barely manages to ask Kyle if he’s gone on a date recently, despite telling him, over a donut breakfast, that he is her best friend. There’s no way to get around the fact that Soderbergh plainly expects us to judge Martha for her diet, for her simplemindedness, and for the shallowness of her relationships.

Though Bubble shouldn’t be taken just as an opportunity to shit on an Oscar winner—Soderbergh is actually a very fine filmmaker, and he’s even done some nice work that’s appealingly sympathetic to the experience of the American working class (yes, I’m thinking of Erin Brockovich)—this film is a startling example of how difficult it is to succeed at breaking convention through realism. By the time Bubble degenerates into the most banal of murder mysteries, Soderbergh has long since condemned himself to a prison of his own making. Too brazen to content himself with conventional storytelling but too uninspired to think outside of any box, he leaves himself trafficking in stereotypes, recycling formal practices that passed as innovative in the hands of others, and imposing artificial generic conventions on an allegedly realist project.

Worst of all, Soderbergh takes his subjects down with him, the people from the Ohio-West Virginia border whose homes and lives have been co-opted as fodder for this art-film sideshow. Let’s call it realistsploitation: Bubble ends with Martha behind bars, like a caged animal in a zoo, presented for our gapes and guffaws. It’s an oddly appropriate close for a film so shockingly devoid of empathy.

On the other hand, Killer of Sheep refuses to impose order of any kind—stereotype, genre, even narrative—on the world it portrays, and in so doing, it somehow offers us the most delightfully shocking thing of all: the briefest glimpse of a real alternative to conventional cinematic storytelling. It isn’t remotely avant-garde, but its approach to narrative is singular in the way it resists judgment, condescension, even explanation.

The film opens with a slow zoom out on a young boy of about 13. His father yells at him between coughs, warning that he needs to “be a man” and defend his younger brother; the context for this lecture remains unexplained. After an abrasive cut that completely disrupts the temporality of the scene, the boy’s mother slaps him in the face, and Burnett fades to his opening credits. The boy never reappears in the film, and while we can probably infer that we’re watching a scene from Stan’s (Henry Gayle Sanders) early childhood, Burnett never does anything to suggest it. In another film, an opening sequence depicting a traumatic experience from the protagonist’s boyhood would serve as an attempt at shorthand psychological motivation for the events that follow. Here, it’s simply one among many moments that have made the character who he is.

Narrative, in real life, exists only in hindsight; it’s a way of imposing order upon an accumulation of moments. There’s a certain power that comes with imposing that order, of leaving this in or taking that out, of implying this cause for that effect. With Killer of Sheep, Burnett resists that position of authority. The film offers nothing more or less than the accumulation of moments. The centerpiece of the film, a somewhat lengthy sequence in which Stan buys a motor, carries it down a flight of stairs with a friend, and then loads it into a truck, only to watch it fall out and break, is utterly heartbreaking. But Burnett is content to leave it just as it is: the motor incident has no specific motivation or repercussion, aside from allowing the viewer to live through one small hope and heartbreak of the character. It’s powerful because it isn’t momentous. The same thing can be said of many of the most enduring moments of the film: Stan’s wife (Kaycee Moore), wanting nothing more than to feel the admiration of her husband, checking her reflection in the cover of a kitchen pot, his daughter (Angela Burnett) singing to her white doll, Stan enjoying the warmth of a cup of tea against his cheek, comparing it to the feeling of making love.

Even when Burnett seems to impose himself upon the action, his film still retains its ambiguity and honesty. Like Bubble, Killer of Sheep features musical interludes that punctuate the action, often set against images of Stan at the slaughterhouse. There’s a visceral brutality to the these scenes—I was made to recall that dazzling slaughterhouse sequence from Fassbinder’s In a Year with Thirteen Moons—and just as Fassbinder uses his scene to mount scathing social critique, Burnett’s formal repetitions suggest a heartwrenching analogy between the ignorant sheep being led to their deaths and the children of Watts: the sheep scenes are almost always inserted between images of children playing violently in the desolate urban landscape, and sometimes, the shot compositions make the parallel explicit (children running, jumping frame right, sheep running frame right; children standing on their heads, the heads of sheep impaled, upside-down). Bleak as this sounds, though, there’s a kind of ethereal beauty to the slaughterhouse scenes that make it impossible to accuse the film of unmitigated hopelessness. Over the last of these sequences, Burnett plays Dinah Washington’s recording of “Unforgettable.” There’s something both ironic and miraculously hopeful in the choice of music that is reflective of Burnett’s remarkable ability to create realist art without exploitation, to preserve the dignity and humanity of his characters. It can’t really be described in words. Of course, so little of this film can be described in words at all, it being built of a cinematic purity that simply defies exegesis.

When I first started working on a pitch for this symposium on “shock” cinema, my instinct was to think of the term as negative or contrarian, to look for films that had offended my sensibilities or somehow set out to break the rules. It’s that instinct that first led me to think about Bubble. In the process, though, I started to wonder whether shock didn’t also mean something more, that it described a work that could challenge our sensibilities or set higher, better standards for our all-too-complacent film culture. If the latter qualifies as “shock” (and I think it does), than Killer of Sheep may well be the most shocking American film I have ever seen, a film so pure in intention, so rich in artistry, and so transcendent in method and execution that it sets a standard that few, if any, films that have followed have even begun to approach.