Maggie the Cat

Karen Wilson on Irma Vep

When Maggie Cheung finally emerges in Irma Vep (1996), after discussion of her as “an action star” and “the Chinese actress,” it’s surprising to see how plain and ordinary the supposed diva looks. Rather than operate just as another movie about making movies, Olivier Assayas’s Irma Vep meditates on Cheung’s star persona. Even though we may watch Maggie for nearly two hours play “herself,” we still are no closer to understanding her than we are to comprehending her character within the film, the mysterious thief, Irma Vep, leader of the Vampires.

Her first feature outside of Asia, Assayas’s film speaks volumes about Cheung’s star quality—her cachet translates fully to the primarily Western audience of this French director’s work. A beauty pageant contestant, the winner of numerous acting prizes including the Hong Kong version of the Academy Awards, and the star of 80 odd films, Cheung’s visage commands loving contemplation; a devotion she inspires in directors she repeatedly works with like Wong Kar-Wai and Stanley Kwan, as well as the characters within Irma Vep. There is something about Maggie Cheung, Irma Vep seems to be saying, that is utterly compelling. This quality that Cheung possesses, the discussion of her abilities as a star and her place within Hong Kong cinema, becomes a focal point within the film’s story and permeates the way we must discuss it critically. To separate Irma Vep from Maggie Cheung’s star persona would be impossible. To pick apart the intermingling between diegesis and nondiegesis, could be a way to begin to map the film’s complexity. How the characters’ fiction and detail surrounding the film’s inception are mingled creates intriguing insights into the text, and Irma Vep explicitly invites this type of biographical speculation that so often spells mere fannishness when used to critique other films.

Assayas relates, in an interview with Zeitgeist Films, that after he met Cheung at a film festival, he decided to construct a short narrative around her filming a fictional movie in Paris directed by Jean-Pierre Léaud as part of a planned triptych with Claire Denis and Atom Egoyan. Concurrently, he was invited to remake a French classic film for television and toyed with re-doing Louis Feuillade’s silent serial Les Vampires (1915-16), which starred silent screen legend Musidora, but circumstances caused him to abandon both projects. Sometime after, he combined the two ideas into one story and wrote the script “quickly, evenly, and with pleasure.” Later, he became reacquainted with Cheung through prolific Hong Kong cinematographer Christopher Doyle and realizing he’d written the Irma Vep script with her in mind, convinced her to star in the picture.

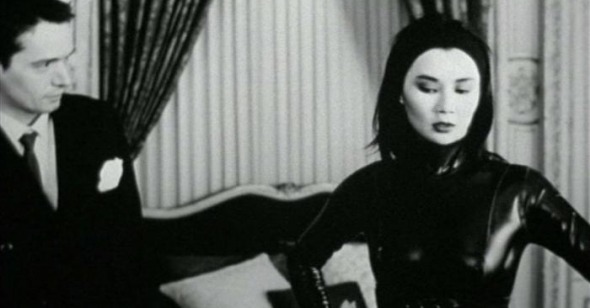

The story begins with Maggie Cheung arriving after shooting has begun, as production office workers buzz about, speaking in French though she only understands English. (From here on, when I refer to Cheung, I mean the actress, while Maggie stands for the character in Irma Vep played by Cheung.) Maggie attempts to prepare for her role, discussing with the director, Rene Vidal (Jean-Pierre Léaud, a French New Wave icon and intriguing stand-in for the former Cahiers du Cinema critic, Assayas) his vision of the character, and getting fitted for her costume at a sex shop: a black latex suit. Shooting does not go entirely on schedule as Vidal begins to suffer from a nervous breakdown. When Vidal’s family packs him off to a sanitarium to recover, the production hires a new director whose vision of Les Vampires does not include an Asian actress as Irma Vep and has Maggie summarily replaced. The remaining crew gets together to screen the footage shot thus far, edited by Vidal into an experimental short, complete with industrial soundtrack and animated lines drawn over the black-and-white image.

This is not the first time Cheung has been required to recreate roles immortalized by silent screen legends. As Ruan Lingyu in Stanley Kwan’s 1992 Center Stage (alternately translated as Ruan Lingyu and Actress), Cheung takes on the task of alternately playing the Chinese actress who committed suicide at the height of her popularity, the roles Ruan played in the scenes Kwan reconstructs, and herself, the actress Maggie Cheung, in the “documentary” interview scenes conducted by Kwan. Foregrounding the construction of these layers, Kwan compares Cheung to Ruan, posing to her questions about becoming a screen immortal. Cheung wisely and modestly demurs when faced with Kwan’s comparisons, as she does when interviewed by Irma Vep’s equally presumptuous characters regarding her star status. Interestingly though, in Irma Vep, the text does not acknowledge her dramatic portrayals in Hong Kong films like Center Stage or Ann Hui’s moving semi-autobiographical film Song of Exile (1990), instead fixating on her action roles, such as Jackie Chan’s damsel-in-distress girlfriend, May, in Police Story (1985) and Thief Catcher in The Heroic Trio (1992). As Maggie tries to point out to the entranced Rene Vidal, most of the memorable action sequences in these movies are performed by stunt doubles. Her difficulty with these physical demands even prevented her from finishing a role, when on the set of Police Story 2 (1988), Cheung’s extensive head injuries forced the producers to use a stand-in for the rest of the film, obscuring her face from view. Despite all of this, Vidal and others still conceptualize Maggie as an action star.

This discussion of Cheung’s status as a representative of Hong Kong cinema continues as a reporter visits the set to interview Maggie. Caught in the gaze of an intrigued outsider, Maggie is grilled by the reporter about her credentials, focusing on the films by John Woo. Maggie reminds him that she has not worked with Woo, but put on the spot to comment on the director, she remonstrates, explaining that he’s so “masculine, I think he’s better with men” as her reason for a disconnect with his style. The reporter contrasts what he sees as Woo’s “strong” cinema with that of Vidal, who he finds “boring,” self-absorbed and “only for the intellectuals” while laughing at Maggie’s attempts to deflect his blanket statements and still remain polite. The sequence ends with the question “You don’t think the intellectual kills the cinema?” hanging over Maggie, implicating her desire to act in a French art film as detrimental to the industry. As the only Asian in the room and known as “the actress from Hong Kong,” Maggie is treated as a spokesperson for that culture, expected to hand down judgments as one of its initiated. But Maggie instead chooses to defend the “dead” European art cinema as an equally valid form of cinematic expression, and in the process shifts her star persona from one associated with action to that of the art house.

With newfound prestige, and after a brief marraige to Assayas, Cheung began alternating between Asian projects such as Comrades, A Love Story and international productions like Wayne Wang’s portrait of 1997 Hong Kong, Chinese Box, with Asian art cinema standby Gong Li. Cheung also continues to work with Wong Kar-wai, starring in his In the Mood for Love (2000) and 2046. Though it would be difficult to conclusively pinpoint what caused the shift in Cheung’s career from action/drama actor to international superstar, I find it intriguing that by appearing in Irma Vep as “herself” Cheung could confront her status as an action heroine, comment critically on her nation’s cinema, and finally, exhibit some serious acting chops. Following a conversation with Vidal about Irma Vep’s narrative purpose and moral makeup just before his final collapse, Maggie dresses as Irma and creeps through the halls of her hotel, just as we’ve seen her do in rehearsal but now with more determination. The restless handheld camera follows her as she enters a neighboring room; Maggie eavesdrops on the woman’s phone conversation and discovers a jeweled necklace beside the sink. She pockets it and in the pouring rain, climbs to the hotel’s rooftop—Irma’s usual domain—where Maggie flings the necklace over the railing. In this elegiac moment, we cannot help but compare Cheung with Musidora and find it difficult to tell who is the real Irma Vep.