On the Rocks

Adam Nayman on Gerry

In my third year of university, I took an avant-garde cinema course taught by a fine professor who didn’t suffer fools. Maybe that was why he was so suspicious of the essay I handed in trying to link Gus Van Sant’s Gerry to the landscape filmmaking of James Benning, the Milwaukee-born filmmaker who has carved out a niche as one of the most rigorous practitioners of what he calls (in an excellent interview with Senses of Cinema) “artist filmmaking.”

Benning’s artistry is at once self-effacing and overwhelming; his serene, fixed-camera perspectives (natural and industrial) are contemplative without the passivity the term usually implies. They are an entreaty to thought, but where an apparent contemporary like Ed Burtysnky (the Canadian photographer at the center of Jennifer Baichwal’s frighteningly beautiful doc Manufactured Landscapes) clearly positions himself as an eco-polemicist, Benning’s concerns are at once more straightforward and less easily pegged.

The fixed-perspective meditations in Ten Skies and 13 Lakes (both contenders alongside Snakes on a Plane in the does-what-it-says-on-the-tin-sweepstakes) have a narrative dimension: the ongoing history on all sides of the frame. But it’s up to the audience to make that leap, from the initial response of “nothing’s happening here” to the durationally-motivated realization that, in fact, so much nothing has happened in this spot (and will happen after Benning leaves) that the image becomes overwhelmingly loquacious—both in what it shows and what, by its very nature as a specific shot in a world home to an infinite multiplicity of perspectives, it elides. What Benning creates, then, is a sense of global simultaneity in a single image.

None of which made its way into my aforementioned essay; fortified by a quote from Jonathan Rosenbaum, I simply pointed out that Benning’s filmography was rife with long, languorous takes of desert vistas, and that Gerry had lots of ‘em, too. Ergo: homage —and a middling grade. I’d probably have been better off working a Béla Tarr angle, since Van Sant’s formal strategies in Gerry—long takes, yes, but mobile ones synched to the beat of human locomotion—were more evocative/derivative of the Hungarian miserablist’s work in Sátántangó and Werckmeister Harmonies. But since Tarr was a narrative filmmaker (albeit a remarkable and unconventional one), that didn’t fit into the assignment’s experimental mandate.

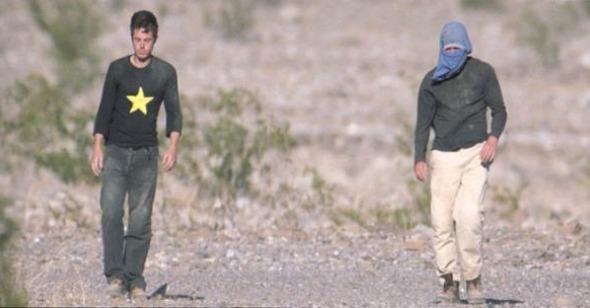

I wrote the paper anyway, which necessitated three viewings of Gerry; in the four years since, I haven’t had the urge to revisit it. Which isn’t to say that it’s bad. If my younger, gauntlet-dropping cinephile self felt the need to prop Gerry up by placing it in a semi-incompatible canon, I can still acknowledge at this point that it’s a beautifully shot (by Harris Savides) and frequently funny little movie. Its particulars are simple: two guys named Gerry (Matt Damon and Casey Affleck) drive out to the American Wilderness to take a walk, ostensibly to arrive at a “thing” (which is, in the best Beckettian tradition, never arrived at nor specified). The Beckettian tradition (or a received variant) informs the action—aimless wandering, circular conversation, existential torpor—that occurs between the moment the two set out and the moment that one Gerry (that’d be Gerry Damon) returns, having suffocated his companion to death in a vaguely self-preserving—or self-extinguishing, or cruel, or desperate, or unintentional, or erotic—gesture.

The “ors” have it in Gerry, which is a different kind of Rorschach test than the ones formulated by Benning. The onus is on us, as Van Sant’s own descriptions of the film aren’t particularly useful. It may in fact be what the director said: the first entry of a “death trilogy” filled out by Elephant and Last Days. But as those other two films invited grand praise on their own self-contained terms (and just for scorekeeping purposes, I like Elephant and abhor Last Days), Gerry requires consideration within its deceptively expansive parameters. I say once again that the “ors” have it, because it could just as easily be Van Sant’s Death Meditation #1 (death by a friend, followed by Elephant’s death by a stranger and Last Days’ death at one’s own hand) as a movie about a kind of psychic suicide, in which the stronger of one personality’s two component parts overwhelms the weaker in a sad but necessary gesture of self-actualization. Or maybe it is a movie about two very modern dudes—guys who talk about Wheel of Fortune and play Ages of Empire—who are by their hipster nature entirely unsuited to adventuring (they each have only a single bottle of water) and get swallowed up by the vast indifference of nature. Or it’s just a series of allusions (Benning, yes; Tarr, definitely; Jarman, subtly, in the use of a certain soulful shade of Blue). Or maybe Van Sant really, really wanted to make people forget the desultorily commercial Finding Forrester and assert that he was the once and future American art-house man now, dawg.

No, that last one is glib: I can’t claim to know Van Sant’s intentions then or now, and the fact that he stuck with this particular aesthetic for three films suggests it was more than just fashion (the fragmented reverie of Paranoid Park is in one way a break, and in others a continuation). That Gerry became something of a film-culture conversation piece (even more so after Elephant won the Palme d’Or) speaks to Van Sant’s very real talent in tethering striking, tangibly physical pictures to airy, intangible concerns.

And also the time-tested value of stranding familiar actors in conceptual structures and letting the incongruity of their presence become an effect in and of itself. Damon and Affleck the younger are both really quite good—Pauline Kael might have derided the Gerrys as Antonionian “walkers”, but there’s communicativeness in their strides, especially once Affleck starts lagging behind. Damon’s success in the Bourne films is predicated on physical acting (just as Daniel Craig’s was in Casino Royale), but he’s particularly solid here–a throwaway gesture early on, the expenditure of energy snapping a branch over his knee before the Gerrys get lost, sticks in the mind once he’s become a shambling mess. It’s a good thing I saw Gerry before Team America: World Police; otherwise, the urge to slur “Maattt Daammon” in response to his floppy-limbed late-film movements would have been disastrous.

I do know people who laughed at Gerry, anyway, and people who were too mortified to laugh—I saw it with one of them. I also remember John Waters writing in Artforum “don’t sleep with anyone who doesn’t love this movie” (oops again). In lieu of any real conclusions about its worth, I’ll trot out my pet concept of the “gateway film,” a portal towards discovering other (not necessarily, but still generally) superior works and other ways of thinking about movies—i.e. I went and watched me some James Benning. Some of Van Sant’s early films reveal an artist finding his voice; Gerry gave its aesthetically restless director the chance to try on some eye-catching formalist clothing. Its enduring value, then, is that it motivates the viewer to seek out the source of its hand-me-downs.