Enter Wong

Sam Ho on As Tears Go By

A bank of television monitors hangs in midair. Across from it glows the huge neon sign of a landmark department store run by mainland Chinese. On the streets below, cars and people bustle. The televisions are not on, but images reflect on them. A cloud of street fog billows across the TV screens.

Much is artificial in the first image of Wong Kar-wai’s first film, As Tears Go By (1988). Yet there is poetry, not just in the visual texture and the urban grace but also in a yearning for nature. The wind, the water molecules that make up the steam, the light that facilitates the reflections—forces of nature set against the plastics of civilization. As Tears Go By, like Hong Kong, is marked by such contradictions. It’s an art film nudging to break through a genre picture; a simple story with a hodgepodge of stylistic flourishes; a violent triad film as well as a tender love story, featuring a kissing scene cherished by fans of Hong Kong cinema as one of the most romantic in Chinese film history.

It’s the mix of formal exuberance and the tender yearning that would make Wong Kar-wai such a darling of the art film circuit. There is a glee to Wong’s exercises in style that is endearingly charming—in his first eight features at least. Such euphoria provides counterbalance to—and also creates harmony with—the melancholy of his tales, which can sometimes smack of masturbatory self-pity, an expression of turn-of-millennium, frustrated individualism.

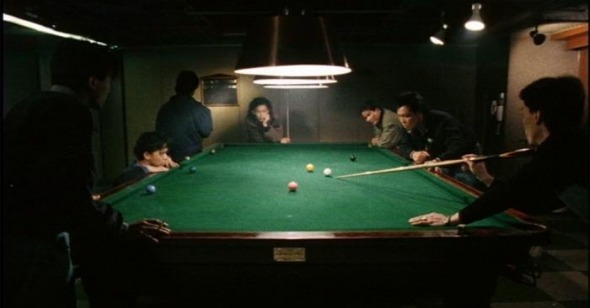

Wong was in the mood for style from the get go. As Tears Go By is in many ways a routine gangster drama, the story of the attempts of small-time mobster Wah (Andy Lau) to balance taking care of his volatile minion and buddy Fly (Jacky Cheung, in an explosive performance) and a love affair with his cousin, Ngor (Maggie Cheung). No ground is broken in the film’s melodramatic depiction of gangland enmity, chivalrous loyalty between blood brothers and conflict between Confucianism ethics and free-market capitalism, punctuated by obligatory episodes of elaborately staged action. Yet the film is also charged with impulses of the art film. Wong took the over-the-top tradition of 1980s Hong Kong cinema and ran with it, adding fresh doses of formal fanfare without diluting the commercial appeal of genre conventions, at the same time challenging established notions of the triad film.

Many of Wong’s signature touches are already on display: the stuttering, smeared visual effect created by step printing that has become Wong’s brand-name imagery; the often poetic and sometimes fetishistic close-ups of objects and body parts; the inserts and cutaways that generate peculiar impressions of time and space; atmospheric renditions of urban environments flanked by ambiguous images or passages of nature; long takes that involve complex and coordinated movements of characters, camera, and lens focus. There are also thematic concerns that recur frequently in later films, such as the duality of characters, the vivid evocations of specific locations and their relationships with those characters, sudden bursts of violence that are integral to their lives, and, of course, the loneliness and profound sense of loss.

Wong’s penchant for eccentric, enigmatic film titles also started here. The name of the classic Rolling Stones tune from which the film takes its title is not heard, though its mournful tone is abundantly sampled. Perhaps it was a way to use the song without paying for royalties, inviting viewers to hum the song in their heads while watching the film. The practice was to continue, in Happy Together (1997), inspired by the 1960s Turtles hit, and In the Mood for Love (2000), altered slightly from the 1930s favorite “I’m in the Mood for Love.”

This also begins a revealing interplay between Chinese and English titles; one could write a book on their culture-crossing intertextuality alone. The Chinese title for Happy Together, Chun Guang Zha Xie, is the same as the Chinese title of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-up (1966). Hua Yang Nian Hua, the Chinese title for In the Mood for Love, is inspired by a 1940s Mandarin pop tune by the songstress Zhou Xuan. The Chinese title for Days of Being Wild, Ah Fei Zheng Zhuan, is the Chinese title for Nicholas Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause, which was very popular and influential in Hong Kong. Wangjiao Kamen, the Chinese title of As Tears Go By, has nothing to do with the Rolling Stones. Translated as “Carmen of Mong Kok,” the film pays tribute to Georges Bizet’s famous opera, but the tempestuous Spanish lass created by the French composer is channeled through the male character Wah, who is stationed in Mong Kok, one of Hong Kong’s busiest districts. (Note: All Chinese titles cited are transliterated in pinyin.)

All that sampling and borrowing in these films titles testify to the permeability of culture, especially in the age of globalization, and Wong’s proclivity to harness the energy released by the crisscross of cultures for his art. The central male relationship in As Tears Go By may be influenced by Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets and the romantic fatalism of the protagonist’s death may recall Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, but Wong made it all his own while also giving what the Hong Kong audience demanded from its genre pictures.

That balance between personal vision and commercial appeal in As Tears Go By, though at times awkward, catapulted Wong to success. The film was both a box-office and critical hit. Jacky Cheung winning best supporting actor at the Hong Kong Film Awards also created a buzz among stars eager for prizes. Film industry godfather Alan Tang, whose company produced Tears, gave Wong a bigger budget and cast for his next project, intended as a two-part film. Little did Tang know that the art film prodding beneath As Tears Go By would rise to the surface in Days of Being Wild, which would be a box-office bomb, albeit an even bigger critical success. The boss would call off the planned sequel, but the damage had been done. An art film director had been unleashed, and the rest is history.