The Unbelievable Truth

By Justin Stewart

The Hoax

Dir. Lasse Hallstrom, U.S., Miramax

What limited pleasures this Hoax supplies can be credited mostly to the fascinating con (and subsequent memoir) that served as its source material. In other words, any movie that recreated, with some semblance of faithfulness, the incredible events of 1970-72 would inherently crackle. Unfortunately, we've been given just that—a safe, comfortable any-movie, content to simply nail the period fashion, juggle a little allegory, and call it a “film version.” When the movie does depart from its origins, the results are either farcical misfiring or butterfingered moral downward spiraling. So while it's never exactly unpalatable, it's also instantly forgettable.

The Hoax is based on Clifford Irving's book of the same name, which tells the story of how he and friend/collaborator Richard Suskind convinced the McGraw-Hill publishing company to release Howard Hughes's autobiography, based on transcripts of Irving's personal meetings with the hermetic billionaire. Fact is, the meetings never happened, nor did Hughes’s many personal letters, masterfully faked by Irving, very much the amateur forger. The sham autobiography got to the very brink of publication before a rare telephone conference between Hughes and seven journalists finally debunked it.

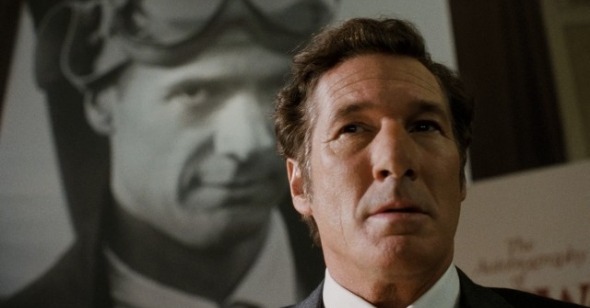

Irving, in his memoir's new preface, on his website, and in interviews has grumbled a bit about the liberties taken with his story. The irony of this man quibbling over facts has already been dutifully pointed out. (He calls the inserted anecdote of his character tricking Suskind into sleeping with hookers "defamatory," as if the autobiography weren't overflowing with humiliating sexual minutiae.) Another complaint is the movie's presentation of Irving in the beginning as struggling and desperate. Irving told the Village Voice, "If I was that guy, I'd shoot myself." And it's true that saddling him with the motive of neediness sucks the banality-of-evil mystery out of the material, in which Irving explains it away with little more than a quote from Jean Le Malchanceux about what a waste of time it is to "establish relationships between acts and motives, effects and causes." Half of the book's fun is glimpsing the charmed life of this established but journeyman author, tanning on his beach resort in Ibiza and conducting international affairs with playboy fatalism. In the film, played by Richard Gere he's barely more a man than Hayden Christensen's bawling fabulist in Shattered Glass (a smarter movie all around).

Although director-subject mispairings can yield interesting movies (Curtis Hanson: an Eminem pseudo-biopic), whoever selected Lasse Hallstrom to tackle such potentially penetrating fare shoulders much of the blame for its mediocrity. The director of The Cider House Rules and The Shipping News never finds his footing on Irving's slippery ground. From flashbulb freeze-frames, to open-road hair-flowing convertible rides scored to CCR's "Up Around the Bend," to forced zeitgeist-grabbing Vietnam/Nixon TV footage, Hallstrom's entire language is marinated in cliché. Suskind, as portrayed by a jowly Alfred Molina (the hypocritical confection binger passed out in the storefront in Hallstrom's Chocolat), is a sweaty clown, so inept in his nervous telling and retelling of a story about taking a prune from Hughes that it's impossible to see how he could have been of any use to Irving (in fact, the real Suskind wrote much of the autobiography). Gere makes a likable weasel, which is essential. You can't take your eyes off of him—knowing he's a liar, you read double meaning and machination into his every word and gesture.

The Hoax is not without its zesty scenes, particularly those in the McGraw-Hill offices, where Irving has to meet roomfuls of his marks face-to-face. It's here—out of the comfort zone and on the battlefield—where you can feel the lie about to crack at any moment. As company president Shelton Fisher, a hair-plugged Stanley Tucci permeates condescending corporate sleaze; it's not difficult to root for Irving against this killjoy. Conversely, Hope Davis, as Andrea Tate, the initial and primary conduit between Irving and the publishers, harbors a sympathetic vulnerability behind her latent desire to make a name for herself with “the big one.” As in the book (in which her name is Beverly Loo), she's the one you most resent Irving for deceiving.

Hallstrom and screenwriter William Wheeler could not commit to an exculpation of Irving, so, perhaps frightened by how much more alluring Gere's shyster is than everyone else, they weighed down the movie's final third with wrecking balls of guilt and moral judgment. The real Irving's bourbon sours become this one’s pain pills (very 2000s), which he pops more and more frequently as his paranoia and identification with Hughes intensify. This “descent into madness” is pure fiction; in his memoirs, his guilt goes little beyond concern for his wife (who cashes Hughes's checks in Swiss banks) and, physically, the loss of his voice. Hallstrom gives us shadowy CIA men and a giggleworthy push and fall of Irving from a rooftop, and it all recalls the disastrously ludicrous latter half of A Beautiful Mind—a shame indeed.