Unwise Blood

By Danielle McCarthy

Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus

Dir. Andrew Douglas, U.S., Films Transit

As I am both a fan of the music of Jim White and a junkie for all things Southern, news of the travelogue Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus elicited from me a cry of “Now that’s my kind of movie!” With White as tour guide, filmmaker Andrew Douglas sets out to document the world of White’s 1997 album, The Mysterious Tale of How I Shouted Wrong-Eyed Jesus. Traveling from Northwest Florida through Louisiana and up to West Virginia, Douglas captures the music and stories of Southerners in attempt to contextualize the peculiar role the religious and the secular plays in the music of the South. Not quite a documentary and nowhere near a narrative, Wrong-Eyed Jesus often feels completely improvised while some moments are obviously staged. A closer look reveals that this beautifully shot portrait is closer to epic mythmaking than straightforward documentation.

Clearly, the intention is spelled out as a young boy narrates at the beginning of the film, “Do you think this place is on a map?” and later White proclaims, “The South is less a state of mind and more an atmosphere.” This is the South viewed through an outsider’s eyes seeing as the British crew and the BBC’s Arena production company has the reigns here. Early on White admits that he has chosen to become a Southerner “as best I can” after a childhood spent sporadically all over the country, including Pensacola, Florida. He defines his choice to go Southern as a “form of divinity.” As White informs us at the beginning of our journey, “If you’ve come to infiltrate the South to learn something important about it you’re gonna need the right car. You can’t show up in a Land Rover or a Lexus and expect poor folks to talk to you and tell you what’s inside their hearts.” And distrustful “the poor folks” should be of Douglas and Co.’s intentions—often the subjects’ heartbreaking life stories are mined for the glorification of a trailer-trash aesthetic.

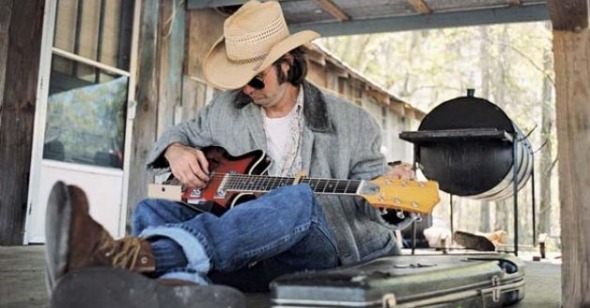

But if it is the film’s intention to capture a mood rather than a reality of the modern South, Wrong-Eyed Jesus succeeds in spades. White’s observations on his adopted homeland are filled with wry, witty truths, and his music is so evocatively paired with the stunning cinematography that the film could be enjoyed simply as an 80-minute music video. The amazing musical performances, staged live in various locales such as a junkyard, hair salon, or a house in the middle of a river appear mysteriously throughout White’s tour. Making appearances are Johnny Dowd, The Handsome Family, David Johansen, and Trailer Bride, as well as unknowns performing traditional American roots music.

Populated with characters straight out of Flannery O’Connor, the film’s main concern is presenting a fire-and-brimstone South populated with saints and sinners. There are prisoners from Louisiana excusing their crimes by blaming boredom. Then there are the denizens of the juke joint, shouting through their drunkenness that they’ll be at confessional on Sunday morning. And then there are the Pentecostals, speaking in tongues and flailing about. In between these two opposing worlds is the music, whether about murder or Jesus, the film posits that the South’s deep religious roots and lack of an upwardly mobile economy produces a tension between the sacred and the secular that is reflected in the songs.

Towards the end of the film, White remarks, “If you’re looking for an essential truth about the South you won’t find it” and quotes Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood, “the blood rules them, they don’t rule the blood.” The film leaves off here, with a mysterious Jesus statue on the side of the road. Despite its Southern atmosphere, Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus is not a film made for Southerners. Its outsider perspective leaves little room for “natives” as anything more than specimens for scrutiny. I don’t doubt the noble intentions of Jim White and his incredible music. It’s the agenda of the film that gives me pause. Of course, there is no truth to be found in the filmic version of Wrong-Eyed Jesus. I believe the music speaks for itself.