Under the Skin

by Michael Nordine

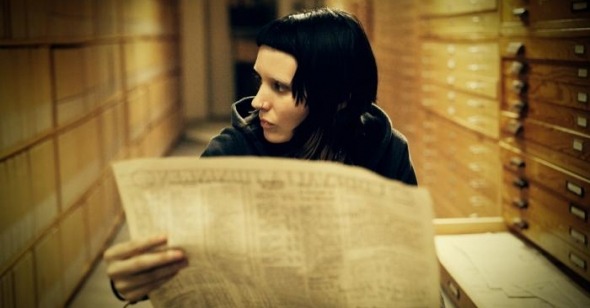

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

Dir. David Fincher, U.S., Columbia Pictures

David Fincher has made a career of turning pulp into prestige. Certainly this has much to do with the technicians and artists he surrounds himself with—Aaron Sorkin and Stephen Zaillian, to name but two recent collaborators, are hardly lightweights in the screenwriting world—but the final product always is distinctly Fincher. He has gained a reputation for meticulousness, for directing the hell out of his movies; even at their most intentionally grimy, there’s a polish to them that’s instantly recognizable. Fincher likes his films grungy but pristine; what at first appears scattershot and ugly tends to be carefully placed. It’s this precision, this attention to detail—think of it as the cinematic equivalent of a forensics expert reconstructing a crime scene backwards from the smallest clue—as much as it is anything else that instantly transformed The Social Network from “the Facebook movie” into the consensus choice for film of the year almost instantly after it premiered in September 2010.

So when it was announced that Fincher was adapting the late Swedish author Stiegg Larsson’s ubiquitous novel The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and remaking Niels Arden Oplev’s film of the same name in the process, it wasn’t much of a surprise. This is a director who thrives on using questionable source material (see: Chuck Palahniuk) as starting points for films that become very much his own. And though I’ve yet to read Larsson’s book—this isn’t for a lack of time spent in airports and subway stations over the last few years—and can’t speak to Fincher’s faithfulness to it, literary reverence is hardly the selling point for a film like this. Almost instantly, it evokes the Scandinavian setting in much the same way most American films do: as an appealingly cold and icy place whose sleek, minimalist architecture is of a piece with the almost exclusively good-looking blonde people who inhabit it. Newspaper headlines are in Swedish, but everyone speaks in accented English (with the occasional “tak” and “hej hej” thrown in for good measure); cold nights are made warmer by vodka and beer. In many ways, this is the most fitting external environment for a Fincher film yet: whereas The Social Network’s dark greens and blues immediately betrayed his presence and even felt tacked on in a story largely taking place in college dorm rooms and, though certainly rife with greed and betrayal, hardly as sinister as something like Zodiac, here the moody color palette he uses is natural to the snowy locale. Aesthetically and thematically, there’s no mistaking who’s in control here or why the story appealed to the director to begin with. As in Se7en and Zodiac, murder and sadism with sometimes-sexual undertones provides Fincher his starting point. But too often this new film merely depicts violence without investigating what impulses went into it. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo certainly doesn’t suffer from a lack of big events, but the way in which the film speeds through those events often feels as though Fincher and Zallian are marking items off a checklist. A rape here, a betrayal there—we’re rarely given an idea what the film thinks of this brutality or even the time to absorb it on our own.

All of this is prefaced by a vapid, overwrought title sequence that plays like an expensive commercial almost entirely divorced from the product it’s selling. For the next hour or so, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo feels similarly dissociated from itself. The plot—a disgraced journalist, Mikael (Daniel Craig), is assisted by a goth/punk computer hacker named Lisbeth (Rooney Mara) to investigate the murder of Harriet Vangar, the niece of wealthy magnate Henrik Vangar (Christopher Plummer), on his family’s island estate some forty years earlier—is fairly by the numbers. In setting all this up, everyone involved banks on the idea that hackers, Nazis, and murder mysteries are inherently sexy and cool. Fair enough, but the proceedings are bogged down by the fact that there’s more to establish than there is to unravel. Characters’ relations with one another criss cross without really going anywhere, and it isn’t until Mikael and Lisbeth finally meet that any chemistry emerges from the many characters and plot devices.

And yet for long—too long—the impression we get is that Lisbeth’s aura of danger and mystique is as strong as it is because there isn’t much behind it. Try as she might to hide it, Lisbeth is damaged, vulnerable, and even frail in her own way—which is to say that she’s a lot like most of us. The piercings and tattoos (including the eponymous ink, whose significance is nil) at first do the opposite of what they’re meant to, as Lisbeth seems less an individual and more a type. When first we meet her, she’s eating microwaved ramen noodles and sipping Coke from a can as she types away on her laptop while wearing fingerless gloves. If that description sounds familiar, it’s probably because this is more or less how every computer hacker has been portrayed on screen for at least two decades—think Angelina Jolie in Hackers or Wayne Knight in Jurassic Park. Where The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo ultimately succeeds—and it takes quite a while to do this—isn’t in convincing us of how cool Lisbeth is, but rather how hurt. That it does so largely in its half-hour denouement is as much a success of these final scenes as it is a failure of the preceding two hours.

But if, as the long and occasionally quite moving denouement suggests, the focus here is less the convoluted story and more the title character, then why waste so much time on the former? By the by, it’s a fairly unremarkable mystery that, with its lugubrious overtones of dread and intrigue, spends a great deal of time trying to convince us of their importance without ever achieving as much. Biblical cryptology and filial molestation work well as starting points for a story of this sort, but too often the inherent drama of these scandalous set pieces is treated as an end unto itself. Even the grand revelation we wait well over two hours for deserves a shoulder-shrug rather than an audible gasp, not least because it’s both difficult to believe and too simple a contrivance. It’s only once we’ve moved past all this window dressing that Lisbeth is finally given the opportunity to define who she is and the onscreen images elicit anything in the way of sympathy or, dare I say, captivation. (Noomi Rapace was equally good in the role as Mara, but she was given less to work with. Mara manages to convince that there’s something deeper beneath the tough-chick facade, and the hollow feeling her sadness leaves us with is the most memorable aspect of the entire movie.)

The plodding story line’s main saving grace is the way it slowly feeds into Lisbeth’s tattered psyche. This is a hurt, frightened woman for whom the slightest attempt at reaching out to someone (namely, Mikael) in the hopes that he’ll affectionately return the gesture is tantamount to a life-or-death risk. But we don’t know this until far too late in the game because, as she says to the object of her affection once the case has been solved, “You and Harriet fucking Vangar have kept me pretty busy.” The sentiment is not lost on this viewer. We may need to get through this investigation to see what makes Lisbeth tick, but we don’t need this much of it. Fincher et al. eventually correct the mistake Arden Oplev and co. made in considering the plot more important than the characters; it is with sympathy and even a pang of sadness, rather than exhaustion, that I recall this film. This is owed most directly to its final thirty minutes in general and the last scene in particular. Everything else we’re meant to care about—the corrupt businessman Mikael wants to bring down, his relationship with his daughter, and the entire Vangar family—is an afterthought compared to the sketch of a relationship at the fringe of the film, which somehow benefits from not being at the center. It’s allowed to rest in the back of one’s mind throughout, slowly taking shape as the more attention-grabbing moments flicker onscreen and quickly fade away. It pulsates, grows, and withers as well, but leaves a mark before it does. One character after another learns: make yourself vulnerable and expect to be hurt.