Detachment

by Michael Joshua Rowin

Day Night Day Night

Dir. Julia Loktev, U.S., IFC Films

[We feel compelled to mention: Spoilers ahead.]

It probably wasnât good timing to watch Julia Loktevâs Day Night Day Night the evening after the worst shooting rampage in United States history. Or perhaps, in a strange way, it was. Held up to the real-world senseless violence of a lone psychotic, Day Nightâs unrevealing portrait of its would-be suicide bomber protagonist comes across as opportunistic, cheap, superficialâand completely effective. The film sets out to rile one into a state of anxious agitation, and, due to the unsustainable alarm of its premise, succeeds in doing so for a fair portion of its running time. But it does so to little purpose: the viewer learns nothing of the suicide bomber, nothing of the religious, political, social, or even personal motivations that would drive a young, ambiguously Muslim-American woman to commit such a devastating act, or what reserves of humanity would cause her to waver in her devotion to destruction.

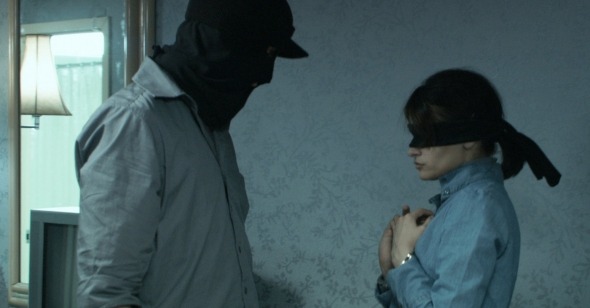

I recently wrote a year-in-review appreciation on Carlos Reygadasâs Battle in Heaven, in which I questioned the critical communityâs lauding of âobjectiveâ realism films (for lack of a better term) like The Death of Mr. Lazarescu and LâEnfant. Now Day Night Day Night demonstrates the true limitations of this style. Following Godardâs famous dictum, âHow can one render the inside? Precisely by staying prudently outside,â Loktev follows an unnamed young woman (Luisa Williams) and remains by her side (or, as in the Dardenne Brothersâ films, mostly hovering at her back) from bus to hotel room to secret hideout to the streets of Times Square as she, with the help of her masked, possibly jihadist conspirators (except for an Irish translator and a deaf bomb expert, they all own American accentsâwhat sort of organization is this, to what sort of ideological allegiance does it subscribe? We never learn), prepares to explode herself and a crowd of bystanders. In the process she is hardly let out of the cameraâs sight, and only on an occasion or two do the camerawork and sound break out of the vice grip of realism to create an environment reflective of our anti-heroineâs subjectivity. The young womanâs name is never mentioned; in the credits she is simply referred to as She. The non-name is appropriate because Day Night doesnât allow her an identity, an inner life. She is a blank, a cipher, an anonymous placeholder for our inability to understand the justifications and ethical distortions of a young person willing to kill strangers for an ideology.

The idea in Day Night Day Night, I can imagine, is that we can never truly understand murderous thoughts and their resultant actions, and so the story of Sheâof her doubtful fanaticism (when alone and forsaken she mutters confessions to her god), her youthful naivetĂ© (Williams is still practically a child, and even under the watch of her commanders covertly noshes on hidden snacks), and her hesitancy (she fails to throw the switch at the moment of truth, only to eventually gather enough fortitude to realize her device has been incorrectly rigged)âmust necessarily be depicted at an artful remove so that her inchoate complexities remain mere hints. This is a film for the cool, detached viewer who nevertheless craves a powerful emotional experienceâjust enough distance, no more than will prevent vicarious thrills. And so Day Night gets our blood pumping, pounding it from our brain to our stomachs by showing âguerrilla-styleâ shots of real NYC crowd scenes as She walks around with a bomb strapped to her back. âThat could be me!â exclaims one in recognition of our post-9/11 vulnerability, in fear of the terrorist acts so familiar to our evening news and easily translatable to our shores. Ultimately, despite Loktevâs attempts to flesh out an abstraction, little difference exists between Day Night Day Night and a Bush Administration âterror alertââin both cases we are thrown into a heightened state of fear and then left bereft of context.

The Dardenne Brothersâ films work because even as they remain carefully at armâs length from their subject they bring the viewer into intimate contact with the subjectâs relationship to his/her environment and fellow human beings, a strategy that involves a sensitive understanding of character and narrative. Day Night Day Night, on the other hand, is all process, with only a will-she-or-wonât-she nail-biting gimmick to send it over. With the characterâs motivations so murky, the viewer is forced to concentrate on the deft skill with which Loktev depicts the suicide bomberâs preparation, a diagram of underground activity. A few moments break away from strict procedure to ironically comment on the situationâs grotesque absurdity, as when the diminutive Williams is outfitted in oversized guerrilla garb for her videotaped martyr message to the world. But such touches were already covered in Paradise Now, a more conventional Palestinian entry from a few years ago. At the time I overpraised Paradise, but its forgettable character psychoanalysis and didactic debating at least engaged more than Day Nightâs topical circumvention. If Loktev is willing enough to trick us into caring about a one-dimensional character played by an awkward, uncharismatic actress (âTo study the unsettled emotional weather on the face of Luisa Williams,â writes Stephen Holden, âis to be reminded of Norma Desmond's famous boast, âWe had faces then.ââ...Dear God) by dangling viewers over an abyss of death, shouldnât she have the courage not to defuse the bomb but to follow through to the disgusting reality of Sheâs actions? Because She, after all her pangs of conscience, does click the button; in a deus ex machina, the bomb fails to ignite. So we never have to see the tragic implications of Sheâs decision, never have to fall into the messy chaos of senseless annihilation.

The Dardenne Brothersâ films work because even as they remain carefully at armâs length from their subject they bring the viewer into intimate contact with the subjectâs relationship to his/her environment and fellow human beings, a strategy that involves a sensitive understanding of character and narrative. Day Night Day Night, on the other hand, is all process, with only a will-she-or-wonât-she nail-biting gimmick to send it over. With the characterâs motivations so murky, the viewer is forced to concentrate on the deft skill with which Loktev depicts the suicide bomberâs preparation, a diagram of underground activity. A few moments break away from strict procedure to ironically comment on the situationâs grotesque absurdity, as when the diminutive Williams is outfitted in oversized guerrilla garb for her videotaped martyr message to the world. But such touches were already covered in Paradise Now, a more conventional Palestinian entry from a few years ago. At the time I overpraised Paradise, but its forgettable character psychoanalysis and didactic debating at least engaged more than Day Nightâs topical circumvention. If Loktev is willing enough to trick us into caring about a one-dimensional character played by an awkward, uncharismatic actress (âTo study the unsettled emotional weather on the face of Luisa Williams,â writes Stephen Holden, âis to be reminded of Norma Desmond's famous boast, âWe had faces then.ââ...Dear God) by dangling viewers over an abyss of death, shouldnât she have the courage not to defuse the bomb but to follow through to the disgusting reality of Sheâs actions? Because She, after all her pangs of conscience, does click the button; in a deus ex machina, the bomb fails to ignite. So we never have to see the tragic implications of Sheâs decision, never have to fall into the messy chaos of senseless annihilation.

Defenders of Day Night Day Night will argue that the film is not about this, that it is about the human story of Sheâs individual dilemma. I donât buy it. If it is, why the expert employment of tight framing and dropped sound (all thatâs missing is the thump-thump of a heartbeat) when Loktev wants to bring us âintoâ Sheâs mind right at the moment of decision? Why drop the layer of objective composure only when it suits the filmâs pulse-quickening designs? Day Night Day Night is not about the morality or immorality of terrorism, itâs about generating a rush. The prolonged coda in which She achieves contact with her potential victims, first by receiving handouts of change from sympathetic passersby and then by getting persistently hit on by a boastful young man, unconvincingly attempts to remedy this superficiality with false overtures to the universality of human foible, or something like that. The panic of her urban anonymity gives way to exposed helplessness, and the viewer is made to sympathize with the vacant, doe-eyed adolescent.

This cannot work because Loktev refuses to enter that torn inner space of angst, rancor, and compassion within the potential murderer (and not just her frightened anticipation of going through with the deed) that seems to be so dreaded by certain filmmakers at the momentâthe outward signs of Sheâs existential plight never matches any personal turmoil weâve experienced in or with her. I wonât use Battle in Heaven as a counter-example again. Instead Iâll refer to Bruno Dumontâs latest, Flanders, a disturbing portrait of a sexually tormented man whose rage finds an unfortunate outlet when heâs stationed in the Middle East. Dumont doesnât combine subjective and objective views as does Reygadas; instead he stays largely âprudently outsideâ his protagonist while finding the appropriate action and behavior to express his state of mind. Day Night Day Night compensates for failing to find its appropriate means by relying on the juice of pending doom. Iâd be more worried about the implications of this cynical tactic if it werenât for films like Flanders to point toward something better and more meaningful.

Click here to read Kristi Mitsudaâs âShotâ on Day Night Day Night.