Fade Out

by Michael Joshua Rowin

Import Export

Dir. Ulrich Seidl, Austria, Palisades Tartan

Early on in Austrian director Ulrich Seidl’s Import Export we’re introduced to Pauli (Paul Hofmann), a short but muscular young man, one of a group of security guards in training. Soon Pauli is seen alone for the first time, playfully fighting in the wintry outdoors with a large and imposing dog that he takes to show his attractive girlfriend at her apartment. The dog frightens the girlfriend, and though Paul tries to reassure her of its natural friendliness, he also teases her by remarking on his animal’s ferocious bite while spitefully—or just stupidly—encouraging it to shred her toy teddy bear. Amazed that Paul would so willfully mock her fear of dogs, the girlfriend gives an ultimatum: the beast or her. We never see the dog again, but neither do we see the girlfriend.

Characters discarded, disappeared, departed—living jetsam—form an appropriate motif for Seidl’s latest film, which looked like it might never be released theatrically in the U.S. after its 2007 Cannes debut. Import Export is vital cinema, but Seidl remains a hard sell. A provocateur who earned his distinctly controversial reputation based on his invasive, voyeuristic, and freakish Nineties documentaries about, among other topics, overly attached pet owners (Animal Love) and self-destructive cover girls (Models) during a particularly ripe age for art-house scandale, Seidl has throughout the past decade disavowed any strict delineation between narrative and nonfiction, fashioning anguished hybrids wherein nonprofessional actors navigate austerely stylized worlds that reflect their director’s forlorn vision. That vision has mutated over time from one of irredeemable misery to one of barely redeemable misery: “Gawking” may be a word that comes to mind when experiencing the worst of humanity as captured by one of Seidl’s lengthy, fixed shots, but so is “unflinching,” and Import Export proves he’s enriched his penchant for the sordid with a nuanced understanding of, yes, the human condition.

The film consists of the parallel tales of Olga (Ekateryna Rak) and the abovementioned Pauli, who never meet. Presumably ditched by his girlfriend, fired from his new security job when a gang of roughs torture and humiliate him, and in debt to several angry acquaintances, Pauli finds a new job with his stepfather, Michael (Michael Thomas), collecting from and delivering candy machines and vintage arcade games through Eastern Europe, ending up in a brutally depressed section of the Ukraine that still hasn’t recovered from the Communist era. Olga makes the opposite journey, starting in that same region of the Ukraine as a single mother, infrequently paid nurse, and inept web cam sex worker (“Put your finger in your ass!” commands a dissatisfied customer) who heads off to Austria to earn better money as a nanny only to wind up in another hospital as a janitor.

Every so often Seidl goes handheld to achieve queasy intimacy with the unpredictable long-form terrors he besets on his proletariat characters (Pauli’s parking lot encounter with the gang is particularly excruciating), but for the most part the framing and pacing of Import Export mirrors the unrelenting circumstances of their lives, informed by the unbridgeable social differences between Eastern and Western Europe. During her walk to the Ukranian hospital she works at, Olga becomes a figure in a post-Soviet, post-industrial landscape nearly epic in its hopelessness—at one point she passes a corroding monument of a soaring plane. Later the home of the upper-middle class Austrian family she works for and lives with is rendered similarly unforgiving by virtue of Seidl’s over-precise compositions. Like the immaculate interiors of the suburban purgatories of his first fiction film, 2001’s Dog Days, bourgeois domestic space becomes a searing antiseptic prison.

Olga’s disposability as an illegal immigrant is made abundantly clear when the Austrian hausfrau fires her for uncertain reasons (she either feels threatened by Olga’s close bond with her spoiled children or finds something suspicious among Olga’s belongings, which she unabashedly goes through right in front of her face). Later on, Pauli will also find inhospitality in the slums and markets of a foreign land, and Pauli and Olga’s stories subtly play off each other (Pauli’s dispiriting encounter with “legitimate” work arrives in the form of a job interview course where a fellow classmate pathetically repeats “I’m a winner” as a motivational mantra), most poignantly during the last section of this bifurcated, picaresque film when, not coincidentally, something resembling hope enters the equation.

Olga’s janitor gig puts her in contact with an elderly man, Schlager (Erich Finsches), whom she especially cares for among a wing of senile and incontinent old men and women—Seidl’s depictions of advanced age and under-funded hospitals are both despairing and honest. Schlager possesses a solid dignity, and his marriage proposal to Olga isn’t portrayed as pathetically delusional, but immensely heartfelt. They even perform a pretend wedding march down a corridor, one of those deadpan comic moments in the cinema of Seidl that elsewhere work as grotesquerie when flipped. Pure fiction has allowed him to become subtler in this regard. The similarly themed Losses Are to Be Expected (1992) offers gratuitous displays of border town weirdness—snatches of local “color”—that lie just outside its Austrian-Czech courtship story; Import Export on the other hand unifies narrative and odd imagery into one seamless, if bleak, whole.

At first glance Seidl’s film might resemble other unwanted demonstrations of melancholy lives touched by globalism, but unlike the hollow connect-the-dots contrivances of inter-European immigration and culture clash reports like The Edge of Heaven, Import Export grants its characters independence from platitudinous screenplay machinations. If anything, these lives must follow the money trail, and thus the film’s maundering tone and inescapable dread. More importantly, Pauli and Olga represent how Seidl has adapted his fall-of-man outlook to account for the free destinies of even the most economically marginalized and physically worn among all lost souls.

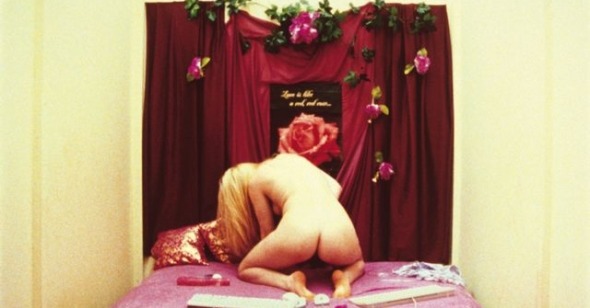

Seidl’s earlier films offer little hint of solace among its horror shows of self-indulgent perversion and vice—the Christ poses struck by shiny nude and bathing suit-clad sunbathers in Dog Days are, I believe, meant ironically. But something happened with Jesus, You Know, his 2003 documentary composed of monologues delivered by six tortured Catholics. It’s not that with this film Seidl found religion, but that he discovered many people don’t choose to wallow in sin, that some struggle—through prayer or a gathering of inner fortitude in the absence of a higher power—to overcome the worst visited upon them. And that’s as good as it gets, he offers. Import Export ends with one last tour through the perdition of the hospital’s geriatric wards, which echo with the weird noises and pleas of old women drawing what may be their last breaths. One of them mutters continuously, “Death . . . death . . . death . . . death . . .” until the film fades out. Moments before this morbid finale Seidl provides one of his characteristically enigmatic images: Olga laughing hysterically at some unknown joke with a roomful of fellow maids. Preceding the concluding note of unavoidable mortality, her cackling stands as the quintessence of laughter in the dark.