Local Hero

By Conor Williams

Peter Hujar’s Day

Dir. Ira Sachs, U.S., Janus Films

Peter Hujar, the handsome, long-faced photographer who passed away from HIV/AIDS in 1987 at the age of 53, has had a remarkable resurgence as of late. In 2018, the Morgan Library & Museum put on Peter Hujar: Speed of Life, a spectacular retrospective that featured Hujar’s many portraits, his subjects ranging from farm geese to New York luminaries like Susan Sontag. His famous book Portraits in Life and Death, with an introduction by Sontag, was recently republished, and 2023 saw the release of Peter Hujar Curated by Elton John at the Fraenkel Gallery as well as a rerelease of Hujar’s periodical Newspaper by Primary Information. Primary Information is also set to release Paul Thek and Peter Hujar: Stay Away from Nothing, an intimate look at the photos and letters produced by the two lovers, and next year the writer Andrew Durbin is publishing The Wonderful World That Almost Was: A Life of Peter Hujar and Paul Thek.

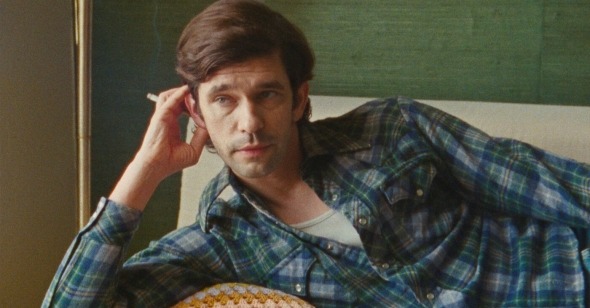

Amid all those books, one other very slim volume was published in 2022, Peter Hujar’s Day, a transcript of a conversation between Hujar and his friend Linda Rosenkrantz that took place in December 1974. Rosenkrantz, a writer, was unsure of how to fill her time from day to day, and had the idea to start asking her friends to write down everything they did in a day and then tell her about it. She was going to tape record these monologues and collect them into a book. That book never came to be, but Peter Hujar’s recollection of his day was rediscovered and printed. Now, Ira Sachs has adapted Rosenkrantz’s project into a feature film of the same name. The filmmaker’s last feature, Passages, was a sexy Paris-set melodrama starring Ben Whishaw, Franz Rogowski, and Adele Exarchopoulos, which faced an NC-17 rating from the prudish and homophobic MPAA. For Peter Hujar’s Day, a film much more pared down than the Fassbinder-inspired Passages, Sachs returned home to New York City. Reuniting with Whishaw, who plays the titular photographer, he enlists Rebecca Hall to portray Rosenkrantz.

Rosenkrantz was no stranger to working in a conversational medium. Her experimental 1968 novel Talk came from recordings of her friends that she made on a beach vacation in 1965. The book was unique in its content—it wasn’t a play or a collection of short stories, but people talking to one another, with only a few details changed for the sake of privacy. According to Sachs, he read Peter Hujar’s Day while working on Passages and immediately got the sense that it would be worth adapting. He fashioned the text into a screenplay, which is to say, technically speaking, Sachs gave the conversation a specific setting—a room to come alive in. Hujar and Rosenkrantz barely leave the apartment in which the film is set. One or two scenes show them standing outside. The film often feels like a one-act play. Peter Hujar’s Day is foremost an experiment, in the same sense as Rosenkrantz’s original mission to document the daily to-dos of her friends. With her project, Rosenkrantz hoped to reveal how much can really happen in one day, and how much one remembers when they stop to focus on the minute details.

Peter Hujar was someone, a meticulous artist who crossed paths with legends from William S. Burroughs to Stevie Wonder. As evidenced by the film, any day in his life would likely contain some element of star power. As for the day in question, most of it concerned a photo assignment he was given by The New York Times to take portraits of Allen Ginsberg. As Hujar makes clear to Rosenkrantz, the poet had a rather brusque and suspicious attitude about the whole thing from the beginning. He objected to The New York Times. Hujar told him he doesn’t work for the Times, this is only his first assignment. He objected to the style. “Portraits? The New York Times is still doing portraits?” Hujar told Ginsberg they can take the pictures in whatever way he wants. He mulled over what outfit is best “to wear to the Lower East Side to meet Allen Ginsberg,” and decided on a red ski jacket. He tells Rosenkrantz that the area really creeped him out, the poverty of it all. He recalls seeing a kid with spray paint streaked on his face, and how the strange and startling image stuck with him. When he met with Ginsberg, the poet wouldn’t stop his incessant Buddhist chanting. “He’s in ohm-land,” Rosenkrantz put it. They walked around the neighborhood and Ginsberg really wanted Hujar to feature the burnt-out buildings, the dilapidated apartments and rubble. The photographer obliged. Later, when they returned to Ginsberg’s apartment, Hujar took a few portraits of him at home, for his own sake. The rest of Hujar’s day consisted of napping, some work in the darkroom, and Chinese food with someone named Vince—likely gay writer and photography critic Vince Aletti.

Ira Sachs achieves something magical with Peter Hujar’s Day: through the filmmaker’s formal restraint, and Ben Whishaw’s remarkable endurance in delivering this monologue with very few interruptions, a second film of sorts is projected onto the screen—the one conjured up in our mind’s eye, narrated by Hujar. There is no need to narrativize or recreate any segment of Hujar’s memories, because the sheer warmth, intimacy, and personality conveyed by Whishaw paints the picture for us. Peter Hujar’s Day is closer to something like documentary recreation, or docu-fiction, than to a traditional artist biopic. With great specificity, the film evokes the New York art world of the 1970s while barely leaving the living room. In 2010, Sachs made an eight-minute short film for Day With(out) Art, World AIDS Day. This film, Last Address, simply showed the exteriors of buildings in which New York artists had last lived before their deaths from HIV/AIDS. Hujar was among the artists (along with his friend and mentee, David Wojnarowicz, who lived in the photographer’s apartment after his death, above what is now Village East Cinemas.) Like this quiet short, Peter Hujar’s Day is a tender record of a moment in a life. Sachs’s film resurrects an artist whose life, like those of so many, was cut tragically short, allowing Peter Hujar to live again in the light of one more day.