Stir It Up

By Nicholas Russell

Pressure

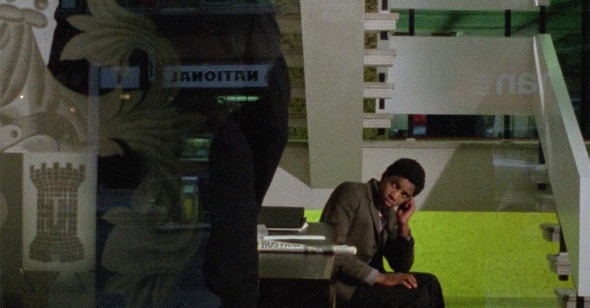

Horace Ové, 1976, U.K., Janus Films

Pressure begins with an English breakfast fried beneath the hummed tune of “Amazing Grace.” The cook, Bopsie Watson, played by Lucita Lijertwood, is the Trinidadian mother of two boys navigating the indifferent, often antagonistic social fabric of 1970s Britain. Tony (Herbert Norville) is only a teenager, born in Britain, with a British accent and an affected fondness for British customs. One gets the sense that for Tony the primary advantage of assimilation is simply invisibility. Tony’s older brother, Colin (Oscar James), is a Black Power activist agitating for change on the street and in smoky meeting halls, his appearance as memorable as a comic book character: green U.S. Army surplus jacket, beanie, and an easy, winning smile.

Back to the breakfast table. Tony lives with his mother and father, Lucas (Frank Singuineau), above Lucas’s grocery store. Pressure is a film that charts tensions within generations as much as across them. The Watson household is bifurcated: two immigrant parents who have sacrificed and continue to sacrifice much for their children butting heads with a younger generation that, despite their parents’ arduous journey to a place of better opportunity, face oppression and discouragement at every turn. Across the table, Tony and Colin, who no longer lives at home, sit as opposing perspectives of the same experience: young black men on colonizers’ soil with seemingly nowhere to go. At Bopsie’s urging, Tony has applied to several jobs, each potential employer rejecting his application on a basis of plausible deniability for his lack of previous work experience. Meanwhile, Colin, who effortfully attempts to get through to Tony about the importance of political organizing and black pride, seems ineffectual at achieving concrete change.

Pressure was the first feature-length film by a black director in Britain, and Ové, previously known for his black-and-white 1968 documentary Baldwin’s Nigger, capturing author James Baldwin and comedian Dick Gregory’s lectures to West Indian students in London, infuses his film with both aesthetic realism and narrative melodrama. The film is a digressive, musically driven bildungsroman told through a series of vignettes that glimpse slivers of contemporary West Indian British life. Ové shoots London as alternately drab and vibrant, the interiors brightly lit like stage sets, while handheld cameras follow Tony and his compatriots into the outside world, public spaces suffused with pedestrian onlookers and a soft haze. Tony flits from one location to the next, from austere offices with smarmy white managers looking at porn instead of doing work to loose gaggles of West Indian misanthropes stealing fruit and trying to enjoy the small freedoms afforded them. Tony is desperate for employment, for acceptance amongst his peers in the wake of the forced generational proximity brought on during his school days, for peace with his intractable older brother and exasperated parents. And yet, he’s also thoroughly unenthused, too familiar with the racist obstacles his parents refuse to acknowledge as legitimate barriers to progress and too placid to follow in his brother’s politically galvanized footsteps.

Unlike most films that outline a nascent radical awakening, Pressure functions by accretion. There is no single instance of racism or injustice that pushes Tony to enlightenment. Indeed, at times, Ové seems to be constructing a kind of racial farce wherein certain figures, whether bigoted white business owners or Black Power movement members, exaggerate their respective performances past the level of archetype. In one scene, Tony runs into Colin at the local market and meets Sister Louise (Sheila Scott-Wilkinson), who rattles off a series of Black Power platitudes more from memory than any genuine passion, a performance of the revolutionary rather than an embodiment of it. But whereas a lesser film would use such instances to undermine the veracity of a movement’s political zeal, Ové demonstrates the degree to which any road to organizing and personal understanding is sometimes paved with half-gestures and hollow imitations.

Tony’s path to a reluctant understanding of the violent world around him is often portrayed via juxtaposition. Throughout the film, the phrase “brothers and sisters” is espoused by Black Power members in a solidaristic tenor while being generalized into a toothless universal invocation from the church pulpit. In one sequence, Ové cuts between a Black Power meeting attended by Colin and a scene of Tony dancing with friends at a nightclub. In one, the importance of agitating for a better life. In the other, an attempt to simply enact that better life into existence. Both modes of being coexist. Later, Colin and his comrades organize a combination meeting and dance that, right at the ascendant point of revelry, is broken up by a swarm of police officers. In Pressure, joy and kinship are not rewards for social progress. Bopsie and Lucas believe in the objective qualities of hard work as if perseverance alone will fend off bigotry. “All you young people give up so quick,” Bopsie says to Tony. The problem for her and for the entire West Indian community is that progress is impossible with such entrenched obstacles in place.

Instead, as Tony comes to understand both his brother’s on-the-ground activism and his parents’ fearful reticence, what’s revealed is the need not only for a robust ethics of solidarity but also the constant implementation of those ethics no matter how attractive or unfashionable. At one point, after a particularly boring church service, Tony’s aunt chides him for falling asleep. Tony weakly protests, but his aunt replies sharply, “You’re here. You might as well do something.” This line reverberates through Pressure. Just what is meant by “doing” is never clear moment to moment, and this is one of Ové’s enduring achievements: a portrait of wisdom acquired not through game enthusiasm and blind action but reluctant learning and careful consideration. Near the end of Pressure, when Tony hesitantly becomes a member of the Black Power movement and Colin has been detained by the police, Tony tries to convince his comrades that the all-or-nothing approach of universally demonizing white people obscures a more incisive, materialist critique of British colonialism. “The only difference between them and us is we can see the bars and the chains, but they can’t.”

Shortly after, Tony falls asleep and dreams of symbolic vengeance, sneaking into an old stone structure in a verdant English field and stabbing a pig laid down on a bed of satin sheets. Upon waking, Tony finds himself where he was before, surrounded by friends and allies, frustrated but alive. Soon, the group takes to the streets, picketing for Colin’s freedom at a roundabout with police nearby. As it begins to rain, the group disperses, along with Tony, who holds his “Power to the people” sign aloft. Ové freezes the frame here, a gray and cold day apart from Tony and his comrades in their conspicuously colorful attire, each ducking away, if only for the moment.