Organized Chaos

By Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer

Problemista

Julio Torres, U.S., A24

Julio Torres’s feature debut Problemista is a comedy about FileMaker Pro. For those unfamiliar, this database software, whose origins date back to the ’80s, is efficient but rather complicated to navigate, depending on who you ask. In Problemista, the software is a recurring punchline. Over the course of the film, its outdated design causes problems for Torres, whose millennial sensibilities predispose him to using Google Sheets as an organizing tool, and for his employer, the disorderly art critic Elizabeth (Tilda Swinton), whose previous intern convinced her to purchase the software to catalog her late partner’s paintings despite her noted middle-aged difficulty with all things computers. No one in Problemista knows how to use FileMaker Pro, yet everyone must interact with it—it’s an easy metaphor for a film that grapples with how most of us are at the mercy of byzantine systems exerting control over our lives.

It’s fitting that Julio Torres’s comedy revolves around things that are difficult to explain—modern furniture, inanimate objects, ghosts—considering how much of its insights are owed to shapeless experiences: getting a U.S. work visa as a Latin American immigrant, getting a job as an artist. His breakout comedy special, My Favorite Shapes (2019), saw him mine laughs from describing a series of objects: a plexiglass square, a chipped plastic rectangle, and a cactus nested in a glass vase, among others. His imaginative storytelling transformed these objects into sentient beings: a square fearful he is just a basic shape, a rectangle having a bad day, and a plant that’s become aware it is merely a replacement for the cactus that previously inhabited the vase it occupies. The comedy resulted from the space between the mundane objects he presented and the fantastical back stories he assigned them, from drawing out the inexpressible rather than defining it.

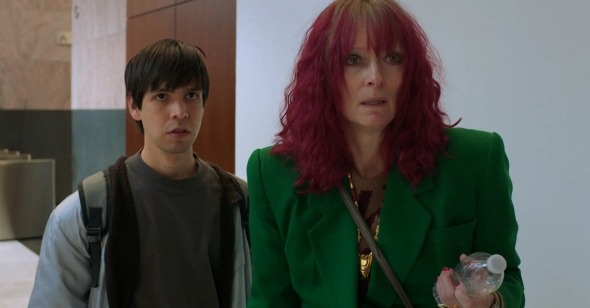

Per Isabella Rossellini’s opening narration, Problemista is “the story of Alejandro,” an aspiring toymaker from El Salvador who moves to New York City (Bushwick to be specific) to fulfill his dream of working at Hasbro. (Notably, Hasbro’s online job portal blocks applicants from outside the “U.S. and its territories.”) But after being denied by Hasbro and getting fired from his position at an archive-cum-cryogenics-lab, he ends up helping an erratic art critic stage a retrospective for her late husband’s art collection because she promises to sponsor his work visa.

To tell this story, Torres takes a different approach from his previous work. By making formless bureaucracies such as bank call centers and the United States immigration system the target of his comedy, he tries to get laughs by merely describing these systems instead of sitting with their strangeness, making the humor didactic rather than thought-provoking. In a scene in which Alejandro calls his bank about his accumulating balance of overdraft fees, Torres displaces the interaction onto a different plane of reality. Instead of having the scene play out as a series of frustrating telephone exchanges, he puts Alejandro and the customer service agent in an infernal cave where their conversation reaches a violent conclusion. When the call ends, the film springs back to reality. As heightened and absurd as Torres’s visualizations of these mundane occurrences are, they never transmit anything beyond that absurdity.

Problemista is a film about the arcane ordering structures that control our lives, and how these put the creation of art in a precarious position; by employing whimsy as its prime method of articulating these frustrations, the film suggests that escapism has become the only way to cope with contemporary living. In its effort to provide catharsis to anyone who has dealt with customer service agents over the phone, had to get an official ID, or tried to mount an art show, the film sanitizes these infuriating bureaucracies by arguing these systems are painful but ultimately amusing inevitabilities, rewarding them an unbefitting logic that negates their unpleasantness.

Noting Torres’s reputation as an outré comedian, it’s rather dismaying how uninventive this first film is. It’s sprinkled with eccentric flourishes—an anthropomorphic representation of Craigslist, a coda set in a future full of R2-D2-like robots—but they act more like comedic cutaways than true provocations. And for all its idiosyncratic characters, there’s nothing distinct about Problemista when compared to other films about Latin American immigrants confronting foreign immigration systems, like Eugenio Derbez’s Instructions Not Included (2013) and Jorge Ramírez Suárez’s Guten Tag, Ramón (2013). Its story beats are predictable: Alejandro needs to find a sponsor, he finds someone who agrees to sponsor him on one condition, he meets that condition after a great deal of emotional and financial struggle, and his sponsor pulls the rug from under him at the last minute—but it’s all okay because she helped him land his dream job at Hasbro. It’s perhaps too classic a story structure for an immigrant without any notable connections.

Everything fits together too neatly in Problemista. Given how aware Torres is about how little makes sense these days—as captured in My Favorite Shapes’ monologues against the instrumentalization of curtains as class-dividers on airplanes or as aesthetic illusions in basement apartments—it’s disappointing to see him turn the puzzling recurrences of contemporary life into a series of cinematic Lego sets. Ultimately, Problemista has a banal message: the labyrinthine systems that control our lives shouldn’t stop aspiring artists from trudging along because no matter how difficult life gets, patience and perseverance are all that matter in the end. It’s a nice sentiment, but it contradicts the film’s own representation of migrants who, in two scenes, literally vanish into thin air when their lawyers tell them they can no longer reside in the United States. Such a genuinely provocative image of the immigration system’s modus operandi feels unfortunately out of place in Torres’s otherwise self-consciously cute story about the struggles of an aspiring toymaker.