In Vain

by Matthew Plouffe

Tarnation

Dir. Jonathan Caouette, U.S., Wellspring

There was a time when young men from small towns in Texas were forced to ship out to New York or Hollywood in order to fulfill their dream of seeing themselves on the big screen. There was a time when the term “filmmaking” was synonymous with a certain financial and technical know-how. Considering the standing ovation at the New York Film Festival, the extended engagement at one of the city's foremost art houses, and the glowing reviews celebrating the $215 dollar iMovie'd mayhem Tarnation and its comely star/director Jonathan Caouette, it's safe to say that those times are long gone.

The irony here is that Caouette did ship out to the big city in order to pursue a career in acting. Little did he know that he had already begun the film that would offer his big break, that he himself had captured many of the images that would grant him celebrity when he began turning camcorders on himself and his troubled family at an early age. Sure to be the subject of innumerable essays on “the democratization of filmmaking” and the effect of new media on how we define and re-define that never-so-loaded phrase, Caouette and Tarnation have only begun to receive the kind of attention which engages the DIY dogma, peddled with abandon heretofore unseen this side of the avant-garde. Confusing the matter, the film's cinema-pique stretches the expanse of the medium and makes it difficult to select an entry point for critical discussion. Sifting through the question marks, two things seem certain: first off, Tarnation's construction—a semi-morphous mass of tropes culled mostly from nonfiction cinema—engages a thoroughly contemporary discourse most of us are inadequately equipped to decipher; second, if this is the future of cinema, we've got a lot to worry about.

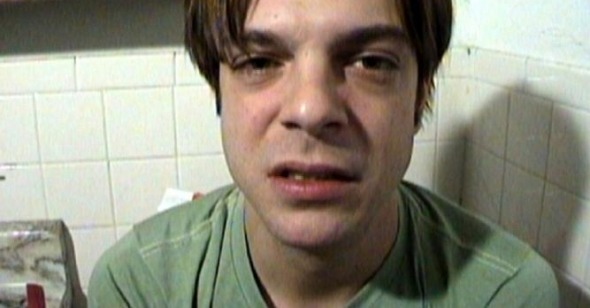

Tarnation documents the life of its filmmaker by suturing old home movies, photographs, answering machine messages, and other tidbits of home-media into an impressively edited collage which records the unenviable rollercoaster ride of Jonathan Caouette's youth. The son of a mother who received shock therapy as a teenager and consequently suffered severe mental illness, Caouette begins his story with a tableaux from his adult life in New York City in which he finds out that she has suffered a lithium overdose. From there he sends us back to The Beginning, where we're introduced to his grandparents, cringe-worthy caricatures in their own right, with whom he spends a vast majority of his time while his mother moves in and out of hospitals. The major events in the life of Jonathan Caouette include witnessing his mother being raped, developing depersonalization disorder at age 12, and co-directing a musical version of David Lynch's Blue Velvet using the music of Marianne Faithfull. It's “the stuff of movies,” to employ the popular cliché; luckily for him, the aspiring actor invariably had a camcorder in hand and always found a way to keep his face in frame.

The film maintains a wonderful forward momentum, propelled in large part by the epileptic editing tactics Caouette uses to splice the myriad media into a coherent whole. The dissolution and reconstruction of medium “activity” is one of Tarnation's enchanting asides. Home movies become peaceful meditations on a moment while distorted still photographs rifle by at a disarming hyper-cinematic pace. Interviewed by Bomb magazine, Caouette spoke of his desire to edit the film like the fever dreams he had as a child. To that end, his pixilated psychedelia is undeniably effective, and one feels as if they're hurtling through a stained-glass funhouse just slightly out of control. It's a fitting formal complement to the fantastic storyline unfolding onscreen, and at the most moving moments, Caouette works within a strange structure of subtle histrionics emotionally anchored to a soothing soundtrack and subtitled narration.

A palpable emotional connection to early adolescence yields his most lucid work as a filmmaker. The portion of the film in which we learn how an underage Caouette frequents a local gay club by posing as petite “Goth” girl, may be its most moving and honest. Unfortunately, one gets the sense that his artistic and intellectual maturation plateaued around the same time he decided to produce Blue Velvet: The Musical in high school. By the time he graduates, hits the road and ends up in New York, one wonders at his unfaltering passion for filming life's inanities in such detail. Frankly, with age, the propensity for documenting himself isn't nearly as cute, and Caouette the Brooklyn Bohemian isn't as riveting as Caouette the dramatic problem-child. The effect is worsened in great part because one can't help but feel that he should have grown out of the habit. Not too long after a montage of close-ups which would have been okay at age ten but seems symptomatic of trite self-obsession at 20, the intellect catches up, or tries to. That is to say, Caouette decides all this drama and all this footage might make a good movie. One question remains for the budding artiste: what the hell is this movie going to be about?

That question becomes impetus and answer. As Caouette stops staring at himself and starts staring through the lens, what purports to be an investigation of his own identity becomes in actuality a quest to find the film's identity. Tarnation's third act, as it were, struggles to grab hold of itself as Caouette focuses on his Mother and his family history in an inadvertently perverted effort to come to terms and make sense of it all (with what, exactly, remains to be seen). While the vicissitudes of his tragicomic childhood are wonderfully gripping, by the time an adult Caouette starts seeking a purpose for his film, his confused intentions seem steeped in the kind of self-exploitative narcissism that fuels humiliating reality television and trashy talk shows. His mother's stories of abuse fuel ire-arousing questions to Granddaddy and at one point the filmmaker even invites his long lost father for an awkward scene on the couch with his Mommie Dearest. The sensitive nature of the subject matter combined with Caouette's callous use of the camera to document all of this, raises complex questions of ethical and artistic integrity. Still, the honesty with which he's imbued much of his film gives one the sense that this one just got away from the guy; the catch-22 here is that any neophyte filmmaker would both be drawn to and entirely ill-equipped to pull off this kind of auto-essay-bio-doc. Unfortuantely, even the attractive candy-coating can't hide the soulessness of this febrile soul search. Caouette never answers the aforementioned question, and without that sturdy motivational foundation, Tarnation finally buckles under its own weight.

We are a young audience witnessing the earliest stages of the New Media epoch. It used to be that “everyone's got a script,” now they've got a movie. Uncommon autodidacticism will surely abound, and one thing we can expect more of is an abundance of movies as messy as this one. It's important that we start opening our eyes in a new manner, as we encounter popular films which open a can of worms simultaneously deep, dangerous, and alluring. Watching Tarnation, I can't help but think that somewhere in the mix lies actual postmodern auteurism along the lines of today's Godard getting experimental with the producers of Jerry Springer. (Notre musique's “Hell” section has a lot in common with Caouette's entire film. Now imagine if Musique never offered “Purgatory” or “Heaven,” and you get some sense of Tarnation's inadequacy.)

To that end, it's worth stating that one of Tarnation's saddest scenes artistically speaking, doubles as a simplistic summary of its failings: the moment when Caouette, having reduced his mother to running out of frame and into the next room with another emotionally disruptive interrogation, yells, “I just want you to help me with my stupid film.” What may be sadder is that audiences have responded by giving Caouette and his stupid film everything he wanted and more: movie stardom, art-world respect, adulation commonly reserved for cinematic revolutionaries. Though Tarnation is a technical achievement in many respects, the film boasts a tagline that makes its success particularly hard to swallow: “Sometimes your greatest achievement is the life you lead.” I can't help but wonder what a real revolutionary like Godard would have to say about that.